Delphi Complete Works of Henry David Thoreau (Illustrated)

A WEEK ON THE CONCORD AND MERRIMACK RIVERS

Where I Lived, and What I Lived For

Former Inhabitants and Winter Visitors

CHAPTER I. CONCORD TO MONTREAL

CHAPTER II. QUEBEC AND MONTMORENCI

CHAPTER IV. THE WALLS OF QUEBEC

CHAPTER V. THE SCENERY OF QUEBEC; AND THE RIVER ST. LAWRENCE

NATURAL HISTORY OF MASSACHUSETTS

WENDELL PHILLIPS BEFORE THE CONCORD LYCEUM

ON THE DUTY OF CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE

THE SUCCESSION OF FOREST TREES

LIST OF POEMS IN CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER

LIST OF POEMS IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER

When breathless noon hath paused on hill and vale

Pens to mend, and hands to guide

Truth — Goodness — Beauty — those celestial thrins

Strange that so many fickle gods

In the busy streets, domains of trade

Last night as I lay gazing with shut eyes

The deeds of king and meanest hedger

T will soon appear if we but look

Each more melodious note I hear

I’ve heard my neighbor’s pump at night

Who sleeps by day and walks by night

When with pale cheek and sunken eye I sang

I’m guided in the darkest night

On the Sun Coming Out in the Afternoon

They who prepare my evening meal below

If from your price ye will not swerve

The Echo of the Sabbath Bell — heard in the Woods

My life has been the poem I would have writ

Greater is the depth of sadness

Ive searched my faculties around

Who equallest the coward’s haste

Only the slave knows of the slave

Great God, I ask thee for no meaner pelf

Within the circuit of this plodding life

Ah, ‘tis in vain the peaceful din

Between the traveller and the setting sun

Have ye no work for a man to do

I sailed up a river with a pleasant wind

Pray to what earth does this sweet cold belong

True kindness is a pure divine affinity

Until at length the north winds blow

Wait not till slaves pronounce the word

Sometimes I hear the veery’s clarion

Not unconcerned Wachusett rears his head

Where’er thou sail’st who sailed with me

I was born upon thy bank river

The moon now rises to her absolute rule

My friends, why should we live?

I mark the summer’s swift decline

On shoulders whirled in some eccentric orbit

Methinks that by a strict behavior

I have rolled near some other spirits path

Brother where dost thou dwell?

On fields oer which the reaper’s hand has passed

The sluggish smoke curls up from some deep dell

On Ponkawtasset, since, we took our way

Yet let us Thank the purblind race

Ye do command me to all virtue ever

Ive seen ye, sisters, on the mountain-side

I am bound, I am bound, for a distant shore

At midnight’s hour I raised my head

Tell me ye wise ones if ye can

My friends, my noble friends, know ye —

But now “no war nor battle’s sound.”

Such water do the gods distill

I have seen some frozenfaced Connecticut

Conscience is instinct bred in the house

Then spend an age in whetting thy desire

We should not mind if on our ear there fell

For though the eaves were rabitted

You Boston folks & Roxbury people

I will obey the strictest law of love

Among the worst of men that ever lived

Tis very fit the ambrosia of the gods

I saw a delicate flower had grown up 2 feet high

The moon moves up her smooth and sheeny path

I’m thankful that my life doth not deceive

To day I climbed a handsome rounded hill

I do not fear my thoughts will die

He knows no change who knows the true

Forever in my dream & in my morning thought

Except, returning, by the Marlboro

FAMILIAR LETTERS OF HENRY DAVID THOREAU

TO HELEN THOREAU (AT TAUNTON).

TO JOHN THOREAU (AT WEST ROXBURY).

TO HELEN THOREAU (AT ROXBURY).

TO HELEN THOREAU (AT ROXBURY).

POSTSCRIPT. (BY MRS. THOREAU.)

TO HELEN THOREAU (AT ROXBURY).

TO MRS. LUCY BROWN 1 (AT PLYMOUTH).

TO MRS. LUCY BROWN (AT PLYMOUTH).

TO MRS. LUCY BROWN (AT PLYMOUTH).

TO MRS. LUCY BROWN (AT PLYMOUTH).

TO MRS. LUCY BROWN (AT PLYMOUTH).

TO RICHARD F. FULLER (AT CAMBRIDGE).

TO MRS. LUCY BROWN (AT PLYMOUTH).

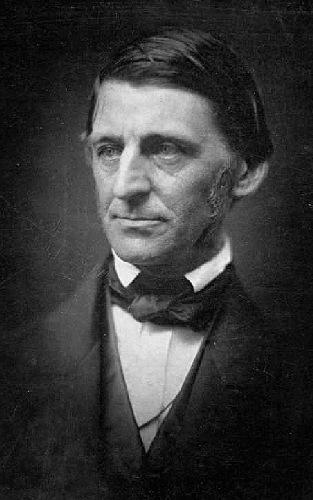

TO R. W. EMERSON (AT NEW YORK).

TO R. W. EMERSON (AT NEW YORK).

TO R. W. EMERSON (AT NEW YORK).

TO R. W. EMERSON (AT NEW YORK).

TO RICHARD F. FULLER (AT CAMBRIDGE).

TO HIS FATHER AND MOTHER (AT CONCORD).

TO SOPHIA THOREAU (AT CONCORD).

TO R. W. EMERSON (AT CONCORD).

TO R. W. EMERSON (AT CONCORD).

TO HIS FATHER AND MOTHER (AT CONCORD).

TO R. W. EMERSON (AT CONCORD).

TO HELEN THOREAU (AT ROXBURY).

TO R. W. EMERSON (AT CONCORD).

TO R. W. EMERSON (AT CONCORD).

TO R. W. EMERSON (AT CONCORD).

TO HELEN THOREAU (AT CONCORD).

II. GOLDEN AGE OF ACHIEVEMENT.

ELLERY CHANNING TO THOREAU (AT CONCORD).

CHARLES LANE TO THOREAU (AT CONCORD).

AGASSIZ TO THOREAU (AT CONCORD).

TO SOPHIA THOREAU (AT BANGOR).

TO R. W. EMERSON (IN ENGLAND).

TO R. W. EMERSON (IN ENGLAND).

TO R. W. EMERSON (IN ENGLAND).

TO R. W. EMERSON (IN ENGLAND).

TO R. W. EMERSON (IN ENGLAND).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO HORACE GREELEY (AT NEW YORK).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT MILTON).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT MILTON).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT MILTON).

TO R. W. EMERSON1 (AT CONCORD).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (IN MILTON).

TO T. W. HIGGINSON (AT BOSTON).

TO MARSTON WATSON (AT PLYMOUTH).

TO SOPHIA THOREAU (AT BANGOR).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO MARSTON WATSON (AT PLYMOUTH).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO DANIEL RICKETSON (AT NEW BEDFORD).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO THOMAS CHOLMONDELEY (AT HODNET).

TO F. B. SANBORN (AT HAMPTON FALLS, N. H.).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO DANIEL RICKETSON (AT NEW BEDFORD).

TO DANIEL RICKETSON (AT NEW BEDFORD).

TO DANIEL RICKETSON (AT NEW BEDFORD).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO DANIEL RICKETSON (AT NEW BEDFORD).

TO DANIEL RICKETSON (AT NEW BEDFORD).

TO DANIEL RICKETSON (AT NEW BEDFORD).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO BRONSON ALCOTT (AT WALPOLE, N. H.).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO DANIEL RICKETSON (AT NEW BEDFORD).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO MARSTON WATSON (AT PLYMOUTH).

TO MARSTON WATSON (AT PLYMOUTH).

TO DANIEL RICKETSON (AT NEW BEDFORD).

TO DANIEL RICKETSON (AT NEW BEDFORD).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO T. W. HIGGINSON (AT WORCESTER).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO DANIEL RICKETSON (AT NEW BEDFORD).

TO DANIEL RICKETSON (AT NEW BEDFORD).

TO DANIEL RICKETSON (AT NEW BEDFORD).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO DANIEL RICKETSON (AT NEW BEDFORD).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO SOPHIA THOREAU (AT CAMPTON, N. H.).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO DANIEL RICKETSON (AT NEW BEDFORD).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO DANIEL RICKETSON (AT NEW BEDFORD).

TO PARKER PILLSBURY (AT CONCORD, N. H.).

T. CHOLMONDELEY TO THOREAU (IN MINNESOTA).

TO HARRISON BLAKE (AT WORCESTER).

TO F. B. SANBORN (AT CONCORD).

TO DANIEL RICKETSON (AT NEW BEDFORD).

TO DANIEL RICKETSON (AT NEW BEDFORD).

SOPHIA THOREAU TO DANIEL RICKETSON (AT NEW BEDFORD).

BRONSON ALCOTT TO DANIEL RICKETSON (AT NEW BEDFORD).

TO MYRON B. BENTON (AT LEEDSVILLE, N. Y.).

INTRODUCTION by Bradford Torrey

THE JOURNAL OF HENRY DAVID THOREAU

HENRY DAVID THOREAU: HIS CHARACTER AND OPINIONS by Robert Louis Stevenson

BROOK FARM AND CONCORD by Henry James

A FABLE FOR CRITICS by James Russell Lowell

HENRY D. THOREAU by Elbert Hubbard

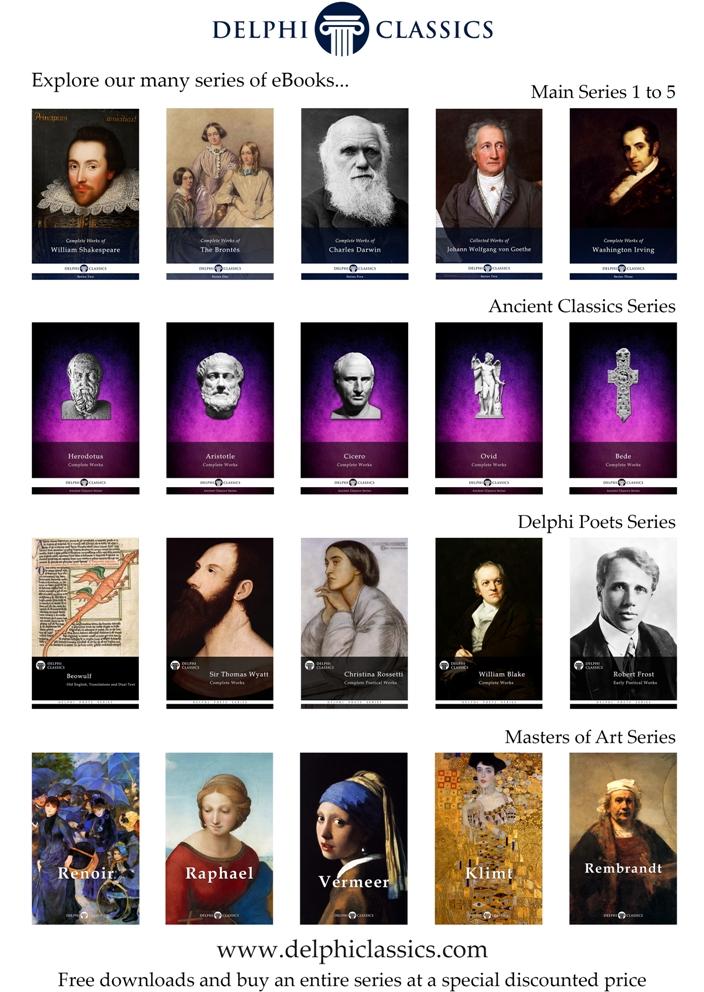

Title Page

The Complete Works of

HENRY DAVID THOREAU

(1817-1862)

Delphi Classics 2013

Version 1

The Complete Works of

HENRY DAVID THOREAU

By Delphi Classics, 2013

The Books

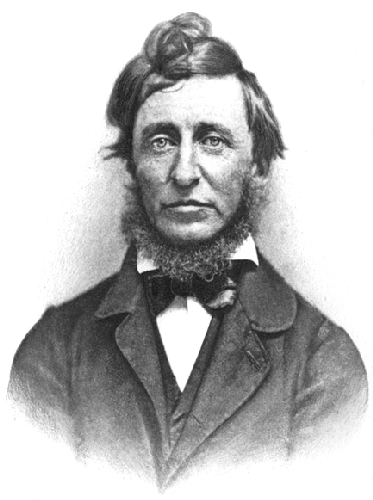

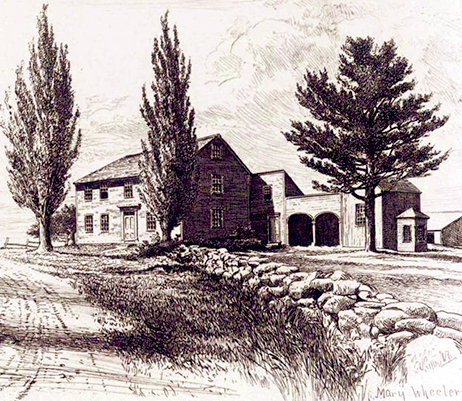

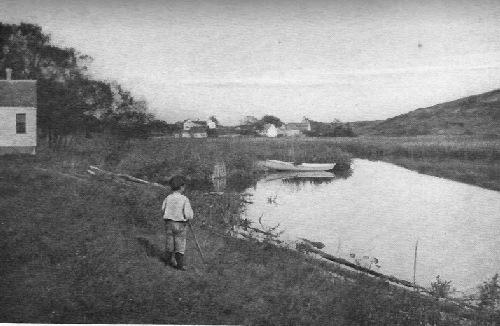

341 Virginia Road, Concord, Massachusetts — Henry David Thoreau’s birthplace. He was born to modest New England parents John Thoreau, a pencil maker, and Cynthia Dunbar.

A sketch of the birthplace in 1897

The house in the late nineteenth century

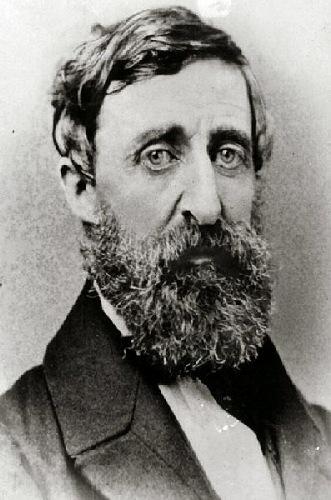

Thoreau as a young man

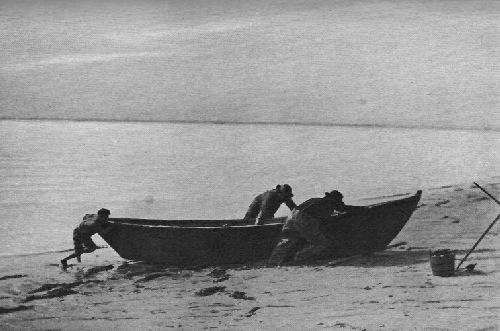

A WEEK ON THE CONCORD AND MERRIMACK RIVERS

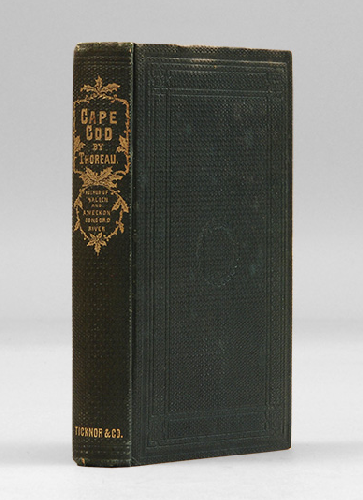

First published in 1849, this book is ostensibly the narrative of a boat trip from Concord, Massachusetts to Concord, New Hampshire and back, which Thoreau had taken with his brother John in 1839. As John had died from tetanus in 1842, Thoreau wrote the book as a tribute to his memory. The book’s first draft was completed while the author was living at Walden Pond. Upon completing the work, Thoreau was unable to find a publisher willing to take it on and so had it published at his own expense. Few copies of the book sold and Thoreau was left with several hundred extra copies, finding himself in debt.

While the book may appear to be a travel journal, broken up into chapters for each day, with some literal description of the journey from Concord, Massachusetts, down the Concord River to the Middlesex Canal, much of the text is in the form of digressions by the Harvard-educated author on diverse topics such as religion, poetry, and history. Thoreau relates these topics back to his own life experiences, often framed by the rapid changes taking place in his native New England during the Industrial Revolution, many of these being changes that Thoreau laments.

The first edition, of which less than 300 sold of the 1,000 copies printed

CONTENTS

The original title page

Where’er thou sail’st who sailed with me,

Though now thou climbest loftier mounts,

And fairer rivers dost ascend,

Be thou my Muse, my Brother — .

I am bound, I am bound, for a distant shore,

By a lonely isle, by a far Azore,

There it is, there it is, the treasure I seek,

On the barren sands of a desolate creek.

I sailed up a river with a pleasant wind,

New lands, new people, and new thoughts to find;

Many fair reaches and headlands appeared,

And many dangers were there to be feared;

But when I remember where I have been,

And the fair landscapes that I have seen,

Thou seemest the only permanent shore,

The cape never rounded, nor wandered o’er.

Fluminaque obliquis cinxit declivia ripis;

Quae, diversa locis, partim sorbentur ab ipsa;

In mare perveniunt partim, campoque recepta

Liberioris aquae, pro ripis litora pulsant.

Ovid, Met. I. 39

He confined the rivers within their sloping banks,

Which in different places are part absorbed by the earth,

Part reach the sea, and being received within the plain

Of its freer waters, beat the shore for banks.

CONCORD RIVER.

“Beneath low hills, in the broad interval

Through which at will our Indian rivulet

Winds mindful still of sannup and of squaw,

Whose pipe and arrow oft the plough unburies,

Here, in pine houses, built of new-fallen trees,

Supplanters of the tribe, the farmers dwell.”

Emerson.

The Musketaquid, or Grass-ground River, though probably as old as the Nile or Euphrates, did not begin to have a place in civilized history, until the fame of its grassy meadows and its fish attracted settlers out of England in 1635, when it received the other but kindred name of Concord from the first plantation on its banks, which appears to have been commenced in a spirit of peace and harmony. It will be Grass-ground River as long as grass grows and water runs here; it will be Concord River only while men lead peaceable lives on its banks. To an extinct race it was grass-ground, where they hunted and fished, and it is still perennial grass-ground to Concord farmers, who own the Great Meadows, and get the hay from year to year. “One branch of it,” according to the historian of Concord, for I love to quote so good authority, “rises in the south part of Hopkinton, and another from a pond and a large cedar-swamp in Westborough,” and flowing between Hopkinton and Southborough, through Framingham, and between Sudbury and Wayland, where it is sometimes called Sudbury River, it enters Concord at the south part of the town, and after receiving the North or Assabeth River, which has its source a little farther to the north and west, goes out at the northeast angle, and flowing between Bedford and Carlisle, and through Billerica, empties into the Merrimack at Lowell. In Concord it is, in summer, from four to fifteen feet deep, and from one hundred to three hundred feet wide, but in the spring freshets, when it overflows its banks, it is in some places nearly a mile wide. Between Sudbury and Wayland the meadows acquire their greatest breadth, and when covered with water, they form a handsome chain of shallow vernal lakes, resorted to by numerous gulls and ducks. Just above Sherman’s Bridge, between these towns, is the largest expanse, and when the wind blows freshly in a raw March day, heaving up the surface into dark and sober billows or regular swells, skirted as it is in the distance with alder-swamps and smoke-like maples, it looks like a smaller Lake Huron, and is very pleasant and exciting for a landsman to row or sail over. The farm-houses along the Sudbury shore, which rises gently to a considerable height, command fine water prospects at this season. The shore is more flat on the Wayland side, and this town is the greatest loser by the flood. Its farmers tell me that thousands of acres are flooded now, since the dams have been erected, where they remember to have seen the white honeysuckle or clover growing once, and they could go dry with shoes only in summer. Now there is nothing but blue-joint and sedge and cut-grass there, standing in water all the year round. For a long time, they made the most of the driest season to get their hay, working sometimes till nine o’clock at night, sedulously paring with their scythes in the twilight round the hummocks left by the ice; but now it is not worth the getting when they can come at it, and they look sadly round to their wood-lots and upland as a last resource.

It is worth the while to make a voyage up this stream, if you go no farther than Sudbury, only to see how much country there is in the rear of us; great hills, and a hundred brooks, and farm-houses, and barns, and haystacks, you never saw before, and men everywhere, Sudbury, that is Southborough men, and Wayland, and Nine-Acre-Corner men, and Bound Rock, where four towns bound on a rock in the river, Lincoln, Wayland, Sudbury, Concord. Many waves are there agitated by the wind, keeping nature fresh, the spray blowing in your face, reeds and rushes waving; ducks by the hundred, all uneasy in the surf, in the raw wind, just ready to rise, and now going off with a clatter and a whistling like riggers straight for Labrador, flying against the stiff gale with reefed wings, or else circling round first, with all their paddles briskly moving, just over the surf, to reconnoitre you before they leave these parts; gulls wheeling overhead, muskrats swimming for dear life, wet and cold, with no fire to warm them by that you know of; their labored homes rising here and there like haystacks; and countless mice and moles and winged titmice along the sunny windy shore; cranberries tossed on the waves and heaving up on the beach, their little red skiffs beating about among the alders; — such healthy natural tumult as proves the last day is not yet at hand. And there stand all around the alders, and birches, and oaks, and maples full of glee and sap, holding in their buds until the waters subside. You shall perhaps run aground on Cranberry Island, only some spires of last year’s pipe-grass above water, to show where the danger is, and get as good a freezing there as anywhere on the Northwest Coast. I never voyaged so far in all my life. You shall see men you never heard of before, whose names you don’t know, going away down through the meadows with long ducking-guns, with water-tight boots wading through the fowl-meadow grass, on bleak, wintry, distant shores, with guns at half-cock, and they shall see teal, blue-winged, green-winged, shelldrakes, whistlers, black ducks, ospreys, and many other wild and noble sights before night, such as they who sit in parlors never dream of. You shall see rude and sturdy, experienced and wise men, keeping their castles, or teaming up their summer’s wood, or chopping alone in the woods, men fuller of talk and rare adventure in the sun and wind and rain, than a chestnut is of meat; who were out not only in ‘75 and 1812, but have been out every day of their lives; greater men than Homer, or Chaucer, or Shakespeare, only they never got time to say so; they never took to the way of writing. Look at their fields, and imagine what they might write, if ever they should put pen to paper. Or what have they not written on the face of the earth already, clearing, and burning, and scratching, and harrowing, and ploughing, and subsoiling, in and in, and out and out, and over and over, again and again, erasing what they had already written for want of parchment.

As yesterday and the historical ages are past, as the work of to-day is present, so some flitting perspectives, and demi-experiences of the life that is in nature are in time veritably future, or rather outside to time, perennial, young, divine, in the wind and rain which never die.

The respectable folks, —

Where dwell they?

They whisper in the oaks,

And they sigh in the hay;

Summer and winter, night and day,

Out on the meadow, there dwell they.

They never die,

Nor snivel, nor cry,

Nor ask our pity

With a wet eye.

A sound estate they ever mend

To every asker readily lend;

To the ocean wealth,

To the meadow health,

To Time his length,

To the rocks strength,

To the stars light,

To the weary night,

To the busy day,

To the idle play;

And so their good cheer never ends,

For all are their debtors, and all their friends.

Concord River is remarkable for the gentleness of its current, which is scarcely perceptible, and some have referred to its influence the proverbial moderation of the inhabitants of Concord, as exhibited in the Revolution, and on later occasions. It has been proposed, that the town should adopt for its coat of arms a field verdant, with the Concord circling nine times round. I have read that a descent of an eighth of an inch in a mile is sufficient to produce a flow. Our river has, probably, very near the smallest allowance. The story is current, at any rate, though I believe that strict history will not bear it out, that the only bridge ever carried away on the main branch, within the limits of the town, was driven up stream by the wind. But wherever it makes a sudden bend it is shallower and swifter, and asserts its title to be called a river. Compared with the other tributaries of the Merrimack, it appears to have been properly named Musketaquid, or Meadow River, by the Indians. For the most part, it creeps through broad meadows, adorned with scattered oaks, where the cranberry is found in abundance, covering the ground like a moss-bed. A row of sunken dwarf willows borders the stream on one or both sides, while at a greater distance the meadow is skirted with maples, alders, and other fluviatile trees, overrun with the grape-vine, which bears fruit in its season, purple, red, white, and other grapes. Still farther from the stream, on the edge of the firm land, are seen the gray and white dwellings of the inhabitants. According to the valuation of 1831, there were in Concord two thousand one hundred and eleven acres, or about one seventh of the whole territory in meadow; this standing next in the list after pasturage and unimproved lands, and, judging from the returns of previous years, the meadow is not reclaimed so fast as the woods are cleared.

Let us here read what old Johnson says of these meadows in his “Wonder-working Providence,” which gives the account of New England from 1628 to 1652, and see how matters looked to him. He says of the Twelfth Church of Christ gathered at Concord: “This town is seated upon a fair fresh river, whose rivulets are filled with fresh marsh, and her streams with fish, it being a branch of that large river of Merrimack. Allwifes and shad in their season come up to this town, but salmon and dace cannot come up, by reason of the rocky falls, which causeth their meadows to lie much covered with water, the which these people, together with their neighbor town, have several times essayed to cut through but cannot, yet it may be turned another way with an hundred pound charge as it appeared.” As to their farming he says: “Having laid out their estate upon cattle at 5 to 20 pound a cow, when they came to winter them with inland hay, and feed upon such wild fother as was never cut before, they could not hold out the winter, but, ordinarily the first or second year after their coming up to a new plantation, many of their cattle died.” And this from the same author “Of the Planting of the 19th Church in the Mattachusets’ Government, called Sudbury”: “This year [does he mean 1654] the town and church of Christ at Sudbury began to have the first foundation stones laid, taking up her station in the inland country, as her elder sister Concord had formerly done, lying further up the same river, being furnished with great plenty of fresh marsh, but, it lying very low is much indamaged with land floods, insomuch that when the summer proves wet they lose part of their hay; yet are they so sufficiently provided that they take in cattle of other towns to winter.”

The sluggish artery of the Concord meadows steals thus unobserved through the town, without a murmur or a pulse-beat, its general course from southwest to northeast, and its length about fifty miles; a huge volume of matter, ceaselessly rolling through the plains and valleys of the substantial earth with the moccasoned tread of an Indian warrior, making haste from the high places of the earth to its ancient reservoir. The murmurs of many a famous river on the other side of the globe reach even to us here, as to more distant dwellers on its banks; many a poet’s stream floating the helms and shields of heroes on its bosom. The Xanthus or Scamander is not a mere dry channel and bed of a mountain torrent, but fed by the everflowing springs of fame; —

“And thou Simois, that as an arrowe, clere

Through Troy rennest, aie downward to the sea”; —

and I trust that I may be allowed to associate our muddy but much abused Concord River with the most famous in history.

“Sure there are poets which did never dream

Upon Parnassus, nor did taste the stream

Of Helicon; we therefore may suppose

Those made not poets, but the poets those.”

The Mississippi, the Ganges, and the Nile, those journeying atoms from the Rocky Mountains, the Himmaleh, and Mountains of the Moon, have a kind of personal importance in the annals of the world. The heavens are not yet drained over their sources, but the Mountains of the Moon still send their annual tribute to the Pasha without fail, as they did to the Pharaohs, though he must collect the rest of his revenue at the point of the sword. Rivers must have been the guides which conducted the footsteps of the first travellers. They are the constant lure, when they flow by our doors, to distant enterprise and adventure, and, by a natural impulse, the dwellers on their banks will at length accompany their currents to the lowlands of the globe, or explore at their invitation the interior of continents. They are the natural highways of all nations, not only levelling the ground and removing obstacles from the path of the traveller, quenching his thirst and bearing him on their bosoms, but conducting him through the most interesting scenery, the most populous portions of the globe, and where the animal and vegetable kingdoms attain their greatest perfection.

I had often stood on the banks of the Concord, watching the lapse of the current, an emblem of all progress, following the same law with the system, with time, and all that is made; the weeds at the bottom gently bending down the stream, shaken by the watery wind, still planted where their seeds had sunk, but erelong to die and go down likewise; the shining pebbles, not yet anxious to better their condition, the chips and weeds, and occasional logs and stems of trees that floated past, fulfilling their fate, were objects of singular interest to me, and at last I resolved to launch myself on its bosom and float whither it would bear me.

SATURDAY.

“Come, come, my lovely fair, and let us try

Those rural delicacies.”

Christ’s Invitation to the Soul. Quarles

SATURDAY.

— * —

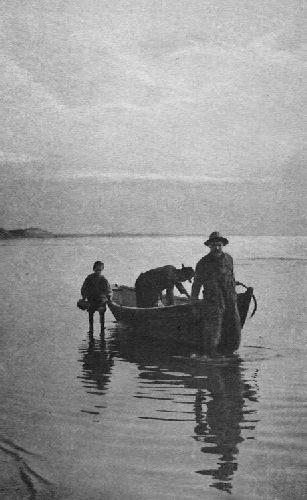

At length, on Saturday, the last day of August, 1839, we two, brothers, and natives of Concord, weighed anchor in this river port; for Concord, too, lies under the sun, a port of entry and departure for the bodies as well as the souls of men; one shore at least exempted from all duties but such as an honest man will gladly discharge. A warm drizzling rain had obscured the morning, and threatened to delay our voyage, but at length the leaves and grass were dried, and it came out a mild afternoon, as serene and fresh as if Nature were maturing some greater scheme of her own. After this long dripping and oozing from every pore, she began to respire again more healthily than ever. So with a vigorous shove we launched our boat from the bank, while the flags and bulrushes courtesied a God-speed, and dropped silently down the stream.

Our boat, which had cost us a week’s labor in the spring, was in form like a fisherman’s dory, fifteen feet long by three and a half in breadth at the widest part, painted green below, with a border of blue, with reference to the two elements in which it was to spend its existence. It had been loaded the evening before at our door, half a mile from the river, with potatoes and melons from a patch which we had cultivated, and a few utensils, and was provided with wheels in order to be rolled around falls, as well as with two sets of oars, and several slender poles for shoving in shallow places, and also two masts, one of which served for a tent-pole at night; for a buffalo-skin was to be our bed, and a tent of cotton cloth our roof. It was strongly built, but heavy, and hardly of better model than usual. If rightly made, a boat would be a sort of amphibious animal, a creature of two elements, related by one half its structure to some swift and shapely fish, and by the other to some strong-winged and graceful bird. The fish shows where there should be the greatest breadth of beam and depth in the hold; its fins direct where to set the oars, and the tail gives some hint for the form and position of the rudder. The bird shows how to rig and trim the sails, and what form to give to the prow that it may balance the boat, and divide the air and water best. These hints we had but partially obeyed. But the eyes, though they are no sailors, will never be satisfied with any model, however fashionable, which does not answer all the requisitions of art. However, as art is all of a ship but the wood, and yet the wood alone will rudely serve the purpose of a ship, so our boat, being of wood, gladly availed itself of the old law that the heavier shall float the lighter, and though a dull water-fowl, proved a sufficient buoy for our purpose.

“Were it the will of Heaven, an osier bough

Were vessel safe enough the seas to plough.”

Some village friends stood upon a promontory lower down the stream to wave us a last farewell; but we, having already performed these shore rites, with excusable reserve, as befits those who are embarked on unusual enterprises, who behold but speak not, silently glided past the firm lands of Concord, both peopled cape and lonely summer meadow, with steady sweeps. And yet we did unbend so far as to let our guns speak for us, when at length we had swept out of sight, and thus left the woods to ring again with their echoes; and it may be many russet-clad children, lurking in those broad meadows, with the bittern and the woodcock and the rail, though wholly concealed by brakes and hardhack and meadow-sweet, heard our salute that afternoon.

We were soon floating past the first regular battle ground of the Revolution, resting on our oars between the still visible abutments of that “North Bridge,” over which in April, 1775, rolled the first faint tide of that war, which ceased not, till, as we read on the stone on our right, it “gave peace to these United States.” As a Concord poet has sung: —

“By the rude bridge that arched the flood,

Their flag to April’s breeze unfurled,

Here once the embattled farmers stood,

And fired the shot heard round the world.

“The foe long since in silence slept;

Alike the conqueror silent sleeps;

And Time the ruined bridge has swept

Down the dark stream which seaward creeps.”

Our reflections had already acquired a historical remoteness from the scenes we had left, and we ourselves essayed to sing.

Ah, ‘t is in vain the peaceful din

That wakes the ignoble town,

Not thus did braver spirits win

A patriot’s renown.

There is one field beside this stream,

Wherein no foot does fall,

But yet it beareth in my dream

A richer crop than all.

Let me believe a dream so dear,

Some heart beat high that day,

Above the petty Province here,

And Britain far away;

Some hero of the ancient mould,

Some arm of knightly worth,

Of strength unbought, and faith unsold,

Honored this spot of earth;

Who sought the prize his heart described,

And did not ask release,

Whose free-born valor was not bribed

By prospect of a peace.

The men who stood on yonder height

That day are long since gone;

Not the same hand directs the fight

And monumental stone.

Ye were the Grecian cities then,

The Romes of modern birth,

Where the New England husbandmen

Have shown a Roman worth.

In vain I search a foreign land

To find our Bunker Hill,

And Lexington and Concord stand

By no Laconian rill.

With such thoughts we swept gently by this now peaceful pasture-ground, on waves of Concord, in which was long since drowned the din of war.

But since we sailed

Some things have failed,

And many a dream

Gone down the stream.

Here then an aged shepherd dwelt,

Who to his flock his substance dealt,

And ruled them with a vigorous crook,

By precept of the sacred Book;

But he the pierless bridge passed o’er,

And solitary left the shore.

Anon a youthful pastor came,

Whose crook was not unknown to fame,

His lambs he viewed with gentle glance,

Spread o’er the country’s wide expanse,

And fed with “Mosses from the Manse.”

Here was our Hawthorne in the dale,

And here the shepherd told his tale.

That slight shaft had now sunk behind the hills, and we had floated round the neighboring bend, and under the new North Bridge between Ponkawtasset and the Poplar Hill, into the Great Meadows, which, like a broad moccason print, have levelled a fertile and juicy place in nature.

On Ponkawtasset, since, we took our way,

Down this still stream to far Billericay,

A poet wise has settled, whose fine ray

Doth often shine on Concord’s twilight day.

Like those first stars, whose silver beams on high,

Shining more brightly as the day goes by,

Most travellers cannot at first descry,

But eyes that wont to range the evening sky,

And know celestial lights, do plainly see,

And gladly hail them, numbering two or three;

For lore that’s deep must deeply studied be,

As from deep wells men read star-poetry.

These stars are never paled, though out of sight,

But like the sun they shine forever bright;

Ay, they are suns, though earth must in its flight

Put out its eyes that it may see their light.

Who would neglect the least celestial sound,

Or faintest light that falls on earthly ground,

If he could know it one day would be found

That star in Cygnus whither we are bound,

And pale our sun with heavenly radiance round?

Gradually the village murmur subsided, and we seemed to be embarked on the placid current of our dreams, floating from past to future as silently as one awakes to fresh morning or evening thoughts. We glided noiselessly down the stream, occasionally driving a pickerel or a bream from the covert of the pads, and the smaller bittern now and then sailed away on sluggish wings from some recess in the shore, or the larger lifted itself out of the long grass at our approach, and carried its precious legs away to deposit them in a place of safety. The tortoises also rapidly dropped into the water, as our boat ruffled the surface amid the willows, breaking the reflections of the trees. The banks had passed the height of their beauty, and some of the brighter flowers showed by their faded tints that the season was verging towards the afternoon of the year; but this sombre tinge enhanced their sincerity, and in the still unabated heats they seemed like the mossy brink of some cool well. The narrow-leaved willow (Salix Purshiana) lay along the surface of the water in masses of light green foliage, interspersed with the large balls of the button-bush. The small rose-colored polygonum raised its head proudly above the water on either hand, and flowering at this season and in these localities, in front of dense fields of the white species which skirted the sides of the stream, its little streak of red looked very rare and precious. The pure white blossoms of the arrow-head stood in the shallower parts, and a few cardinals on the margin still proudly surveyed themselves reflected in the water, though the latter, as well as the pickerel-weed, was now nearly out of blossom. The snake-head, Chelone glabra, grew close to the shore, while a kind of coreopsis, turning its brazen face to the sun, full and rank, and a tall dull red flower, Eupatorium purpureum, or trumpet-weed, formed the rear rank of the fluvial array. The bright blue flowers of the soap-wort gentian were sprinkled here and there in the adjacent meadows, like flowers which Proserpine had dropped, and still farther in the fields or higher on the bank were seen the purple Gerardia, the Virginian rhexia, and drooping neottia or ladies’-tresses; while from the more distant waysides which we occasionally passed, and banks where the sun had lodged, was reflected still a dull yellow beam from the ranks of tansy, now past its prime. In short, Nature seemed to have adorned herself for our departure with a profusion of fringes and curls, mingled with the bright tints of flowers, reflected in the water. But we missed the white water-lily, which is the queen of river flowers, its reign being over for this season. He makes his voyage too late, perhaps, by a true water clock who delays so long. Many of this species inhabit our Concord water. I have passed down the river before sunrise on a summer morning between fields of lilies still shut in sleep; and when, at length, the flakes of sunlight from over the bank fell on the surface of the water, whole fields of white blossoms seemed to flash open before me, as I floated along, like the unfolding of a banner, so sensible is this flower to the influence of the sun’s rays.

As we were floating through the last of these familiar meadows, we observed the large and conspicuous flowers of the hibiscus, covering the dwarf willows, and mingled with the leaves of the grape, and wished that we could inform one of our friends behind of the locality of this somewhat rare and inaccessible flower before it was too late to pluck it; but we were just gliding out of sight of the village spire before it occurred to us that the farmer in the adjacent meadow would go to church on the morrow, and would carry this news for us; and so by the Monday, while we should be floating on the Merrimack, our friend would be reaching to pluck this blossom on the bank of the Concord.

After a pause at Ball’s Hill, the St. Ann’s of Concord voyageurs, not to say any prayer for the success of our voyage, but to gather the few berries which were still left on the hills, hanging by very slender threads, we weighed anchor again, and were soon out of sight of our native village. The land seemed to grow fairer as we withdrew from it. Far away to the southwest lay the quiet village, left alone under its elms and buttonwoods in mid afternoon; and the hills, notwithstanding their blue, ethereal faces, seemed to cast a saddened eye on their old playfellows; but, turning short to the north, we bade adieu to their familiar outlines, and addressed ourselves to new scenes and adventures. Naught was familiar but the heavens, from under whose roof the voyageur never passes; but with their countenance, and the acquaintance we had with river and wood, we trusted to fare well under any circumstances.

From this point, the river runs perfectly straight for a mile or more to Carlisle Bridge, which consists of twenty wooden piers, and when we looked back over it, its surface was reduced to a line’s breadth, and appeared like a cobweb gleaming in the sun. Here and there might be seen a pole sticking up, to mark the place where some fisherman had enjoyed unusual luck, and in return had consecrated his rod to the deities who preside over these shallows. It was full twice as broad as before, deep and tranquil, with a muddy bottom, and bordered with willows, beyond which spread broad lagoons covered with pads, bulrushes, and flags.

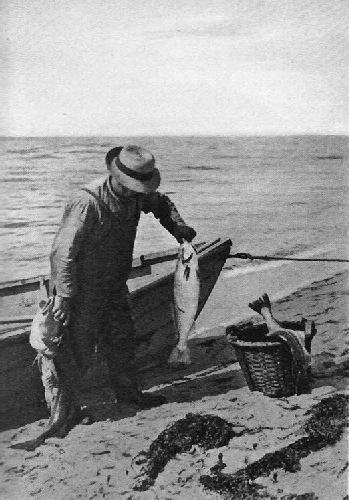

Late in the afternoon we passed a man on the shore fishing with a long birch pole, its silvery bark left on, and a dog at his side, rowing so near as to agitate his cork with our oars, and drive away luck for a season; and when we had rowed a mile as straight as an arrow, with our faces turned towards him, and the bubbles in our wake still visible on the tranquil surface, there stood the fisher still with his dog, like statues under the other side of the heavens, the only objects to relieve the eye in the extended meadow; and there would he stand abiding his luck, till he took his way home through the fields at evening with his fish. Thus, by one bait or another, Nature allures inhabitants into all her recesses. This man was the last of our townsmen whom we saw, and we silently through him bade adieu to our friends.

The characteristics and pursuits of various ages and races of men are always existing in epitome in every neighborhood. The pleasures of my earliest youth have become the inheritance of other men. This man is still a fisher, and belongs to an era in which I myself have lived. Perchance he is not confounded by many knowledges, and has not sought out many inventions, but how to take many fishes before the sun sets, with his slender birchen pole and flaxen line, that is invention enough for him. It is good even to be a fisherman in summer and in winter. Some men are judges these August days, sitting on benches, even till the court rises; they sit judging there honorably, between the seasons and between meals, leading a civil politic life, arbitrating in the case of Spaulding versus Cummings, it may be, from highest noon till the red vesper sinks into the west. The fisherman, meanwhile, stands in three feet of water, under the same summer’s sun, arbitrating in other cases between muckworm and shiner, amid the fragrance of water-lilies, mint, and pontederia, leading his life many rods from the dry land, within a pole’s length of where the larger fishes swim. Human life is to him very much like a river,

“renning aie downward to the sea.”

This was his observation. His honor made a great discovery in bailments.

I can just remember an old brown-coated man who was the Walton of this stream, who had come over from Newcastle, England, with his son, — the latter a stout and hearty man who had lifted an anchor in his day. A straight old man he was who took his way in silence through the meadows, having passed the period of communication with his fellows; his old experienced coat, hanging long and straight and brown as the yellow-pine bark, glittering with so much smothered sunlight, if you stood near enough, no work of art but naturalized at length. I often discovered him unexpectedly amid the pads and the gray willows when he moved, fishing in some old country method, — for youth and age then went a fishing together, — full of incommunicable thoughts, perchance about his own Tyne and Northumberland. He was always to be seen in serene afternoons haunting the river, and almost rustling with the sedge; so many sunny hours in an old man’s life, entrapping silly fish; almost grown to be the sun’s familiar; what need had he of hat or raiment any, having served out his time, and seen through such thin disguises? I have seen how his coeval fates rewarded him with the yellow perch, and yet I thought his luck was not in proportion to his years; and I have seen when, with slow steps and weighed down with aged thoughts, he disappeared with his fish under his low-roofed house on the skirts of the village. I think nobody else saw him; nobody else remembers him now, for he soon after died, and migrated to new Tyne streams. His fishing was not a sport, nor solely a means of subsistence, but a sort of solemn sacrament and withdrawal from the world, just as the aged read their Bibles.

Whether we live by the seaside, or by the lakes and rivers, or on the prairie, it concerns us to attend to the nature of fishes, since they are not phenomena confined to certain localities only, but forms and phases of the life in nature universally dispersed. The countless shoals which annually coast the shores of Europe and America are not so interesting to the student of nature, as the more fertile law itself, which deposits their spawn on the tops of mountains, and on the interior plains; the fish principle in nature, from which it results that they may be found in water in so many places, in greater or less numbers. The natural historian is not a fisherman, who prays for cloudy days and good luck merely, but as fishing has been styled “a contemplative man’s recreation,” introducing him profitably to woods and water, so the fruit of the naturalist’s observations is not in new genera or species, but in new contemplations still, and science is only a more contemplative man’s recreation. The seeds of the life of fishes are everywhere disseminated, whether the winds waft them, or the waters float them, or the deep earth holds them; wherever a pond is dug, straightway it is stocked with this vivacious race. They have a lease of nature, and it is not yet out. The Chinese are bribed to carry their ova from province to province in jars or in hollow reeds, or the water-birds to transport them to the mountain tarns and interior lakes. There are fishes wherever there is a fluid medium, and even in clouds and in melted metals we detect their semblance. Think how in winter you can sink a line down straight in a pasture through snow and through ice, and pull up a bright, slippery, dumb, subterranean silver or golden fish! It is curious, also, to reflect how they make one family, from the largest to the smallest. The least minnow that lies on the ice as bait for pickerel, looks like a huge sea-fish cast up on the shore. In the waters of this town there are about a dozen distinct species, though the inexperienced would expect many more.

It enhances our sense of the grand security and serenity of nature, to observe the still undisturbed economy and content of the fishes of this century, their happiness a regular fruit of the summer. The Fresh-Water Sun-Fish, Bream, or Ruff, Pomotis vulgaris, as it were, without ancestry, without posterity, still represents the Fresh-Water Sun-Fish in nature. It is the most common of all, and seen on every urchin’s string; a simple and inoffensive fish, whose nests are visible all along the shore, hollowed in the sand, over which it is steadily poised through the summer hours on waving fin. Sometimes there are twenty or thirty nests in the space of a few rods, two feet wide by half a foot in depth, and made with no little labor, the weeds being removed, and the sand shoved up on the sides, like a bowl. Here it may be seen early in summer assiduously brooding, and driving away minnows and larger fishes, even its own species, which would disturb its ova, pursuing them a few feet, and circling round swiftly to its nest again: the minnows, like young sharks, instantly entering the empty nests, meanwhile, and swallowing the spawn, which is attached to the weeds and to the bottom, on the sunny side. The spawn is exposed to so many dangers, that a very small proportion can ever become fishes, for beside being the constant prey of birds and fishes, a great many nests are made so near the shore, in shallow water, that they are left dry in a few days, as the river goes down. These and the lamprey’s are the only fishes’ nests that I have observed, though the ova of some species may be seen floating on the surface. The breams are so careful of their charge that you may stand close by in the water and examine them at your leisure. I have thus stood over them half an hour at a time, and stroked them familiarly without frightening them, suffering them to nibble my fingers harmlessly, and seen them erect their dorsal fins in anger when my hand approached their ova, and have even taken them gently out of the water with my hand; though this cannot be accomplished by a sudden movement, however dexterous, for instant warning is conveyed to them through their denser element, but only by letting the fingers gradually close about them as they are poised over the palm, and with the utmost gentleness raising them slowly to the surface. Though stationary, they keep up a constant sculling or waving motion with their fins, which is exceedingly graceful, and expressive of their humble happiness; for unlike ours, the element in which they live is a stream which must be constantly resisted. From time to time they nibble the weeds at the bottom or overhanging their nests, or dart after a fly or a worm. The dorsal fin, besides answering the purpose of a keel, with the anal, serves to keep the fish upright, for in shallow water, where this is not covered, they fall on their sides. As you stand thus stooping over the bream in its nest, the edges of the dorsal and caudal fins have a singular dusty golden reflection, and its eyes, which stand out from the head, are transparent and colorless. Seen in its native element, it is a very beautiful and compact fish, perfect in all its parts, and looks like a brilliant coin fresh from the mint. It is a perfect jewel of the river, the green, red, coppery, and golden reflections of its mottled sides being the concentration of such rays as struggle through the floating pads and flowers to the sandy bottom, and in harmony with the sunlit brown and yellow pebbles. Behind its watery shield it dwells far from many accidents inevitable to human life.

There is also another species of bream found in our river, without the red spot on the operculum, which, according to M. Agassiz, is undescribed.

The Common Perch, Perca flavescens, which name describes well the gleaming, golden reflections of its scales as it is drawn out of the water, its red gills standing out in vain in the thin element, is one of the handsomest and most regularly formed of our fishes, and at such a moment as this reminds us of the fish in the picture which wished to be restored to its native element until it had grown larger; and indeed most of this species that are caught are not half grown. In the ponds there is a light-colored and slender kind, which swim in shoals of many hundreds in the sunny water, in company with the shiner, averaging not more than six or seven inches in length, while only a few larger specimens are found in the deepest water, which prey upon their weaker brethren. I have often attracted these small perch to the shore at evening, by rippling the water with my fingers, and they may sometimes be caught while attempting to pass inside your hands. It is a tough and heedless fish, biting from impulse, without nibbling, and from impulse refraining to bite, and sculling indifferently past. It rather prefers the clear water and sandy bottoms, though here it has not much choice. It is a true fish, such as the angler loves to put into his basket or hang at the top of his willow twig, in shady afternoons along the banks of the stream. So many unquestionable fishes he counts, and so many shiners, which he counts and then throws away. Old Josselyn in his “New England’s Rarities,” published in 1672, mentions the Perch or River Partridge.

The Chivin, Dace, Roach, Cousin Trout, or whatever else it is called, Leuciscus pulchellus, white and red, always an unexpected prize, which, however, any angler is glad to hook for its rarity. A name that reminds us of many an unsuccessful ramble by swift streams, when the wind rose to disappoint the fisher. It is commonly a silvery soft-scaled fish, of graceful, scholarlike, and classical look, like many a picture in an English book. It loves a swift current and a sandy bottom, and bites inadvertently, yet not without appetite for the bait. The minnows are used as bait for pickerel in the winter. The red chivin, according to some, is still the same fish, only older, or with its tints deepened as they think by the darker water it inhabits, as the red clouds swim in the twilight atmosphere. He who has not hooked the red chivin is not yet a complete angler. Other fishes, methinks, are slightly amphibious, but this is a denizen of the water wholly. The cork goes dancing down the swift-rushing stream, amid the weeds and sands, when suddenly, by a coincidence never to be remembered, emerges this fabulous inhabitant of another element, a thing heard of but not seen, as if it were the instant creation of an eddy, a true product of the running stream. And this bright cupreous dolphin was spawned and has passed its life beneath the level of your feet in your native fields. Fishes too, as well as birds and clouds, derive their armor from the mine. I have heard of mackerel visiting the copper banks at a particular season; this fish, perchance, has its habitat in the Coppermine River. I have caught white chivin of great size in the Aboljacknagesic, where it empties into the Penobscot, at the base of Mount Ktaadn, but no red ones there. The latter variety seems not to have been sufficiently observed.

The Dace, Leuciscus argenteus, is a slight silvery minnow, found generally in the middle of the stream, where the current is most rapid, and frequently confounded with the last named.

The Shiner, Leuciscus crysoleucas, is a soft-scaled and tender fish, the victim of its stronger neighbors, found in all places, deep and shallow, clear and turbid; generally the first nibbler at the bait, but, with its small mouth and nibbling propensities, not easily caught. It is a gold or silver bit that passes current in the river, its limber tail dimpling the surface in sport or flight. I have seen the fry, when frightened by something thrown into the water, leap out by dozens, together with the dace, and wreck themselves upon a floating plank. It is the little light-infant of the river, with body armor of gold or silver spangles, slipping, gliding its life through with a quirk of the tail, half in the water, half in the air, upward and ever upward with flitting fin to more crystalline tides, yet still abreast of us dwellers on the bank. It is almost dissolved by the summer heats. A slighter and lighter colored shiner is found in one of our ponds.

The Pickerel, Esox reticulatus, the swiftest, wariest, and most ravenous of fishes, which Josselyn calls the Fresh-Water or River Wolf, is very common in the shallow and weedy lagoons along the sides of the stream. It is a solemn, stately, ruminant fish, lurking under the shadow of a pad at noon, with still, circumspect, voracious eye, motionless as a jewel set in water, or moving slowly along to take up its position, darting from time to time at such unlucky fish or frog or insect as comes within its range, and swallowing it at a gulp. I have caught one which had swallowed a brother pickerel half as large as itself, with the tail still visible in its mouth, while the head was already digested in its stomach. Sometimes a striped snake, bound to greener meadows across the stream, ends its undulatory progress in the same receptacle. They are so greedy and impetuous that they are frequently caught by being entangled in the line the moment it is cast. Fishermen also distinguish the brook pickerel, a shorter and thicker fish than the former.

The Horned Pout, Pimelodus nebulosus, sometimes called Minister, from the peculiar squeaking noise it makes when drawn out of the water, is a dull and blundering fellow, and like the eel vespertinal in his habits, and fond of the mud. It bites deliberately as if about its business. They are taken at night with a mass of worms strung on a thread, which catches in their teeth, sometimes three or four, with an eel, at one pull. They are extremely tenacious of life, opening and shutting their mouths for half an hour after their heads have been cut off. A bloodthirsty and bullying race of rangers, inhabiting the fertile river bottoms, with ever a lance in rest, and ready to do battle with their nearest neighbor. I have observed them in summer, when every other one had a long and bloody scar upon his back, where the skin was gone, the mark, perhaps, of some fierce encounter. Sometimes the fry, not an inch long, are seen darkening the shore with their myriads.

The Suckers, Catostomi Bostonienses and tuberculati, Common and Horned, perhaps on an average the largest of our fishes, may be seen in shoals of a hundred or more, stemming the current in the sun, on their mysterious migrations, and sometimes sucking in the bait which the fisherman suffers to float toward them. The former, which sometimes grow to a large size, are frequently caught by the hand in the brooks, or like the red chivin, are jerked out by a hook fastened firmly to the end of a stick, and placed under their jaws. They are hardly known to the mere angler, however, not often biting at his baits, though the spearer carries home many a mess in the spring. To our village eyes, these shoals have a foreign and imposing aspect, realizing the fertility of the seas.

The Common Eel, too, Muraena Bostoniensis, the only species of eel known in the State, a slimy, squirming creature, informed of mud, still squirming in the pan, is speared and hooked up with various success. Methinks it too occurs in picture, left after the deluge, in many a meadow high and dry.

In the shallow parts of the river, where the current is rapid, and the bottom pebbly, you may sometimes see the curious circular nests of the Lamprey Eel, Petromyzon Americanus, the American Stone-Sucker, as large as a cart-wheel, a foot or two in height, and sometimes rising half a foot above the surface of the water. They collect these stones, of the size of a hen’s egg, with their mouths, as their name implies, and are said to fashion them into circles with their tails. They ascend falls by clinging to the stones, which may sometimes be raised, by lifting the fish by the tail. As they are not seen on their way down the streams, it is thought by fishermen that they never return, but waste away and die, clinging to rocks and stumps of trees for an indefinite period; a tragic feature in the scenery of the river bottoms worthy to be remembered with Shakespeare’s description of the sea-floor. They are rarely seen in our waters at present, on account of the dams, though they are taken in great quantities at the mouth of the river in Lowell. Their nests, which are very conspicuous, look more like art than anything in the river.

If we had leisure this afternoon, we might turn our prow up the brooks in quest of the classical trout and the minnows. Of the last alone, according to M. Agassiz, several of the species found in this town are yet undescribed. These would, perhaps, complete the list of our finny contemporaries in the Concord waters.

Salmon, Shad, and Alewives were formerly abundant here, and taken in weirs by the Indians, who taught this method to the whites, by whom they were used as food and as manure, until the dam, and afterward the canal at Billerica, and the factories at Lowell, put an end to their migrations hitherward; though it is thought that a few more enterprising shad may still occasionally be seen in this part of the river. It is said, to account for the destruction of the fishery, that those who at that time represented the interests of the fishermen and the fishes, remembering between what dates they were accustomed to take the grown shad, stipulated, that the dams should be left open for that season only, and the fry, which go down a month later, were consequently stopped and destroyed by myriads. Others say that the fish-ways were not properly constructed. Perchance, after a few thousands of years, if the fishes will be patient, and pass their summers elsewhere, meanwhile, nature will have levelled the Billerica dam, and the Lowell factories, and the Grass-ground River run clear again, to be explored by new migratory shoals, even as far as the Hopkinton pond and Westborough swamp.

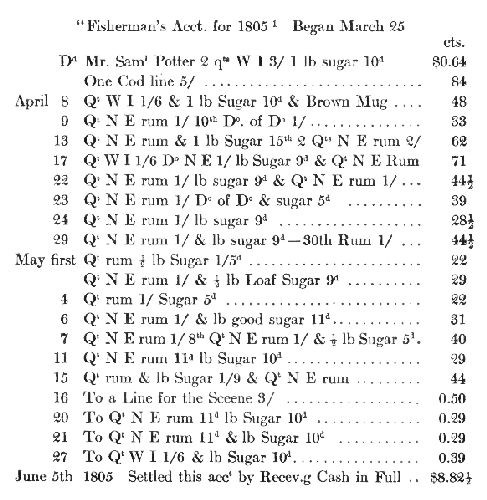

One would like to know more of that race, now extinct, whose seines lie rotting in the garrets of their children, who openly professed the trade of fishermen, and even fed their townsmen creditably, not skulking through the meadows to a rainy afternoon sport. Dim visions we still get of miraculous draughts of fishes, and heaps uncountable by the river-side, from the tales of our seniors sent on horseback in their childhood from the neighboring towns, perched on saddle-bags, with instructions to get the one bag filled with shad, the other with alewives. At least one memento of those days may still exist in the memory of this generation, in the familiar appellation of a celebrated train-band of this town, whose untrained ancestors stood creditably at Concord North Bridge. Their captain, a man of piscatory tastes, having duly warned his company to turn out on a certain day, they, like obedient soldiers, appeared promptly on parade at the appointed time, but, unfortunately, they went undrilled, except in the manuoevres of a soldier’s wit and unlicensed jesting, that May day; for their captain, forgetting his own appointment, and warned only by the favorable aspect of the heavens, as he had often done before, went a-fishing that afternoon, and his company thenceforth was known to old and young, grave and gay, as “The Shad,” and by the youths of this vicinity this was long regarded as the proper name of all the irregular militia in Christendom. But, alas! no record of these fishers’ lives remains that we know, unless it be one brief page of hard but unquestionable history, which occurs in Day Book No. 4, of an old trader of this town, long since dead, which shows pretty plainly what constituted a fisherman’s stock in trade in those days. It purports to be a Fisherman’s Account Current, probably for the fishing season of the year 1805, during which months he purchased daily rum and sugar, sugar and rum, N. E. and W. I., “one cod line,” “one brown mug,” and “a line for the seine”; rum and sugar, sugar and rum, “good loaf sugar,” and “good brown,” W. I. and N. E., in short and uniform entries to the bottom of the page, all carried out in pounds, shillings, and pence, from March 25th to June 5th, and promptly settled by receiving “cash in full” at the last date. But perhaps not so settled altogether. These were the necessaries of life in those days; with salmon, shad, and alewives, fresh and pickled, he was thereafter independent on the groceries. Rather a preponderance of the fluid elements; but such is the fisherman’s nature. I can faintly remember to have seen this same fisher in my earliest youth, still as near the river as he could get, with uncertain undulatory step, after so many things had gone down stream, swinging a scythe in the meadow, his bottle like a serpent hid in the grass; himself as yet not cut down by the Great Mower.

Surely the fates are forever kind, though Nature’s laws are more immutable than any despot’s, yet to man’s daily life they rarely seem rigid, but permit him to relax with license in summer weather. He is not harshly reminded of the things he may not do. She is very kind and liberal to all men of vicious habits, and certainly does not deny them quarter; they do not die without priest. Still they maintain life along the way, keeping this side the Styx, still hearty, still resolute, “never better in their lives”; and again, after a dozen years have elapsed, they start up from behind a hedge, asking for work and wages for able-bodied men. Who has not met such

“a beggar on the way,

Who sturdily could gang? ….

Who cared neither for wind nor wet,

In lands where’er he past?”

“That bold adopts each house he views, his own;

Makes every pulse his checquer, and, at pleasure,

Walks forth, and taxes all the world, like Caesar”; —

as if consistency were the secret of health, while the poor inconsistent aspirant man, seeking to live a pure life, feeding on air, divided against himself, cannot stand, but pines and dies after a life of sickness, on beds of down.

The unwise are accustomed to speak as if some were not sick; but methinks the difference between men in respect to health is not great enough to lay much stress upon. Some are reputed sick and some are not. It often happens that the sicker man is the nurse to the sounder.

Shad are still taken in the basin of Concord River at Lowell, where they are said to be a month earlier than the Merrimack shad, on account of the warmth of the water. Still patiently, almost pathetically, with instinct not to be discouraged, not to be reasoned with, revisiting their old haunts, as if their stern fates would relent, and still met by the Corporation with its dam. Poor shad! where is thy redress? When Nature gave thee instinct, gave she thee the heart to bear thy fate? Still wandering the sea in thy scaly armor to inquire humbly at the mouths of rivers if man has perchance left them free for thee to enter. By countless shoals loitering uncertain meanwhile, merely stemming the tide there, in danger from sea foes in spite of thy bright armor, awaiting new instructions, until the sands, until the water itself, tell thee if it be so or not. Thus by whole migrating nations, full of instinct, which is thy faith, in this backward spring, turned adrift, and perchance knowest not where men do not dwell, where there are not factories, in these days. Armed with no sword, no electric shock, but mere Shad, armed only with innocence and a just cause, with tender dumb mouth only forward, and scales easy to be detached. I for one am with thee, and who knows what may avail a crow-bar against that Billerica dam? — Not despairing when whole myriads have gone to feed those sea monsters during thy suspense, but still brave, indifferent, on easy fin there, like shad reserved for higher destinies. Willing to be decimated for man’s behoof after the spawning season. Away with the superficial and selfish phil-anthropy of men, — who knows what admirable virtue of fishes may be below low-water-mark, bearing up against a hard destiny, not admired by that fellow-creature who alone can appreciate it! Who hears the fishes when they cry? It will not be forgotten by some memory that we were contemporaries. Thou shalt erelong have thy way up the rivers, up all the rivers of the globe, if I am not mistaken. Yea, even thy dull watery dream shall be more than realized. If it were not so, but thou wert to be overlooked at first and at last, then would not I take their heaven. Yes, I say so, who think I know better than thou canst. Keep a stiff fin then, and stem all the tides thou mayst meet.

At length it would seem that the interests, not of the fishes only, but of the men of Wayland, of Sudbury, of Concord, demand the levelling of that dam. Innumerable acres of meadow are waiting to be made dry land, wild native grass to give place to English. The farmers stand with scythes whet, waiting the subsiding of the waters, by gravitation, by evaporation or otherwise, but sometimes their eyes do not rest, their wheels do not roll, on the quaking meadow ground during the haying season at all. So many sources of wealth inaccessible. They rate the loss hereby incurred in the single town of Wayland alone as equal to the expense of keeping a hundred yoke of oxen the year round. One year, as I learn, not long ago, the farmers standing ready to drive their teams afield as usual, the water gave no signs of falling; without new attraction in the heavens, without freshet or visible cause, still standing stagnant at an unprecedented height. All hydrometers were at fault; some trembled for their English even. But speedy emissaries revealed the unnatural secret, in the new float-board, wholly a foot in width, added to their already too high privileges by the dam proprietors. The hundred yoke of oxen, meanwhile, standing patient, gazing wishfully meadowward, at that inaccessible waving native grass, uncut but by the great mower Time, who cuts so broad a swathe, without so much as a wisp to wind about their horns.

That was a long pull from Ball’s Hill to Carlisle Bridge, sitting with our faces to the south, a slight breeze rising from the north, but nevertheless water still runs and grass grows, for now, having passed the bridge between Carlisle and Bedford, we see men haying far off in the meadow, their heads waving like the grass which they cut. In the distance the wind seemed to bend all alike. As the night stole over, such a freshness was wafted across the meadow that every blade of cut grass seemed to teem with life. Faint purple clouds began to be reflected in the water, and the cow-bells tinkled louder along the banks, while, like sly water-rats, we stole along nearer the shore, looking for a place to pitch our camp.

At length, when we had made about seven miles, as far as Billerica, we moored our boat on the west side of a little rising ground which in the spring forms an island in the river. Here we found huckleberries still hanging upon the bushes, where they seemed to have slowly ripened for our especial use. Bread and sugar, and cocoa boiled in river water, made our repast, and as we had drank in the fluvial prospect all day, so now we took a draft of the water with our evening meal to propitiate the river gods, and whet our vision for the sights it was to behold. The sun was setting on the one hand, while our eminence was contributing its shadow to the night, on the other. It seemed insensibly to grow lighter as the night shut in, and a distant and solitary farm-house was revealed, which before lurked in the shadows of the noon. There was no other house in sight, nor any cultivated field. To the right and left, as far as the horizon, were straggling pine woods with their plumes against the sky, and across the river were rugged hills, covered with shrub oaks, tangled with grape-vines and ivy, with here and there a gray rock jutting out from the maze. The sides of these cliffs, though a quarter of a mile distant, were almost heard to rustle while we looked at them, it was such a leafy wilderness; a place for fauns and satyrs, and where bats hung all day to the rocks, and at evening flitted over the water, and fire-flies husbanded their light under the grass and leaves against the night. When we had pitched our tent on the hillside, a few rods from the shore, we sat looking through its triangular door in the twilight at our lonely mast on the shore, just seen above the alders, and hardly yet come to a stand-still from the swaying of the stream; the first encroachment of commerce on this land. There was our port, our Ostia. That straight geometrical line against the water and the sky stood for the last refinements of civilized life, and what of sublimity there is in history was there symbolized.

For the most part, there was no recognition of human life in the night, no human breathing was heard, only the breathing of the wind. As we sat up, kept awake by the novelty of our situation, we heard at intervals foxes stepping about over the dead leaves, and brushing the dewy grass close to our tent, and once a musquash fumbling among the potatoes and melons in our boat, but when we hastened to the shore we could detect only a ripple in the water ruffling the disk of a star. At intervals we were serenaded by the song of a dreaming sparrow or the throttled cry of an owl, but after each sound which near at hand broke the stillness of the night, each crackling of the twigs, or rustling among the leaves, there was a sudden pause, and deeper and more conscious silence, as if the intruder were aware that no life was rightfully abroad at that hour. There was a fire in Lowell, as we judged, this night, and we saw the horizon blazing, and heard the distant alarm-bells, as it were a faint tinkling music borne to these woods. But the most constant and memorable sound of a summer’s night, which we did not fail to hear every night afterward, though at no time so incessantly and so favorably as now, was the barking of the house-dogs, from the loudest and hoarsest bark to the faintest aerial palpitation under the eaves of heaven, from the patient but anxious mastiff to the timid and wakeful terrier, at first loud and rapid, then faint and slow, to be imitated only in a whisper; wow-wow-wow-wow — wo — wo — w — w. Even in a retired and uninhabited district like this, it was a sufficiency of sound for the ear of night, and more impressive than any music. I have heard the voice of a hound, just before daylight, while the stars were shining, from over the woods and river, far in the horizon, when it sounded as sweet and melodious as an instrument. The hounding of a dog pursuing a fox or other animal in the horizon, may have first suggested the notes of the hunting-horn to alternate with and relieve the lungs of the dog. This natural bugle long resounded in the woods of the ancient world before the horn was invented. The very dogs that sullenly bay the moon from farm-yards in these nights excite more heroism in our breasts than all the civil exhortations or war sermons of the age. “I would rather be a dog, and bay the moon,” than many a Roman that I know. The night is equally indebted to the clarion of the cock, with wakeful hope, from the very setting of the sun, prematurely ushering in the dawn. All these sounds, the crowing of cocks, the baying of dogs, and the hum of insects at noon, are the evidence of nature’s health or sound state. Such is the never-failing beauty and accuracy of language, the most perfect art in the world; the chisel of a thousand years retouches it.

At length the antepenultimate and drowsy hours drew on, and all sounds were denied entrance to our ears.

Who sleeps by day and walks by night,

Will meet no spirit but some sprite.

SUNDAY.

“The river calmly flows,

Through shining banks, through lonely glen,

Where the owl shrieks, though ne’er the cheer of men

Has stirred its mute repose,

Still if you should walk there, you would go there again.”

CHANNING.

“The Indians tell us of a beautiful River lying far to the south, which they call Merrimack.”

Sieur de Monts, Relations of the jesuits, 1604.

SUNDAY.

— * —

In the morning the river and adjacent country were covered with a dense fog, through which the smoke of our fire curled up like a still subtiler mist; but before we had rowed many rods, the sun arose and the fog rapidly dispersed, leaving a slight steam only to curl along the surface of the water. It was a quiet Sunday morning, with more of the auroral rosy and white than of the yellow light in it, as if it dated from earlier than the fall of man, and still preserved a heathenish integrity: —

An early unconverted Saint,

Free from noontide or evening taint,

Heathen without reproach,

That did upon the civil day encroach,

And ever since its birth

Had trod the outskirts of the earth.

But the impressions which the morning makes vanish with its dews, and not even the most “persevering mortal” can preserve the memory of its freshness to mid-day. As we passed the various islands, or what were islands in the spring, rowing with our backs down stream, we gave names to them. The one on which we had camped we called Fox Island, and one fine densely wooded island surrounded by deep water and overrun by grape-vines, which looked like a mass of verdure and of flowers cast upon the waves, we named Grape Island. From Ball’s Hill to Billerica meeting-house, the river was still twice as broad as in Concord, a deep, dark, and dead stream, flowing between gentle hills and sometimes cliffs, and well wooded all the way. It was a long woodland lake bordered with willows. For long reaches we could see neither house nor cultivated field, nor any sign of the vicinity of man. Now we coasted along some shallow shore by the edge of a dense palisade of bulrushes, which straightly bounded the water as if clipt by art, reminding us of the reed forts of the East-Indians, of which we had read; and now the bank slightly raised was overhung with graceful grasses and various species of brake, whose downy stems stood closely grouped and naked as in a vase, while their heads spread several feet on either side. The dead limbs of the willow were rounded and adorned by the climbing mikania, Mikania scandens, which filled every crevice in the leafy bank, contrasting agreeably with the gray bark of its supporter and the balls of the button-bush. The water willow, Salix Purshiana, when it is of large size and entire, is the most graceful and ethereal of our trees. Its masses of light green foliage, piled one upon another to the height of twenty or thirty feet, seemed to float on the surface of the water, while the slight gray stems and the shore were hardly visible between them. No tree is so wedded to the water, and harmonizes so well with still streams. It is even more graceful than the weeping willow, or any pendulous trees, which dip their branches in the stream instead of being buoyed up by it. Its limbs curved outward over the surface as if attracted by it. It had not a New England but an Oriental character, reminding us of trim Persian gardens, of Haroun Alraschid, and the artificial lakes of the East.

As we thus dipped our way along between fresh masses of foliage overrun with the grape and smaller flowering vines, the surface was so calm, and both air and water so transparent, that the flight of a kingfisher or robin over the river was as distinctly seen reflected in the water below as in the air above. The birds seemed to flit through submerged groves, alighting on the yielding sprays, and their clear notes to come up from below. We were uncertain whether the water floated the land, or the land held the water in its bosom. It was such a season, in short, as that in which one of our Concord poets sailed on its stream, and sung its quiet glories.

“There is an inward voice, that in the stream

Sends forth its spirit to the listening ear,

And in a calm content it floweth on,

Like wisdom, welcome with its own respect.

Clear in its breast lie all these beauteous thoughts,

It doth receive the green and graceful trees,

And the gray rocks smile in its peaceful arms.”

And more he sung, but too serious for our page. For every oak and birch too growing on the hill-top, as well as for these elms and willows, we knew that there was a graceful ethereal and ideal tree making down from the roots, and sometimes Nature in high tides brings her mirror to its foot and makes it visible. The stillness was intense and almost conscious, as if it were a natural Sabbath, and we fancied that the morning was the evening of a celestial day. The air was so elastic and crystalline that it had the same effect on the landscape that a glass has on a picture, to give it an ideal remoteness and perfection. The landscape was clothed in a mild and quiet light, in which the woods and fences checkered and partitioned it with new regularity, and rough and uneven fields stretched away with lawn-like smoothness to the horizon, and the clouds, finely distinct and picturesque, seemed a fit drapery to hang over fairy-land. The world seemed decked for some holiday or prouder pageantry, with silken streamers flying, and the course of our lives to wind on before us like a green lane into a country maze, at the season when fruit-trees are in blossom.

Why should not our whole life and its scenery be actually thus fair and distinct? All our lives want a suitable background. They should at least, like the life of the anchorite, be as impressive to behold as objects in the desert, a broken shaft or crumbling mound against a limitless horizon. Character always secures for itself this advantage, and is thus distinct and unrelated to near or trivial objects, whether things or persons. On this same stream a maiden once sailed in my boat, thus unattended but by invisible guardians, and as she sat in the prow there was nothing but herself between the steersman and the sky. I could then say with the poet, —

“Sweet falls the summer air

Over her frame who sails with me;

Her way like that is beautifully free,

Her nature far more rare,

And is her constant heart of virgin purity.”

At evening still the very stars seem but this maiden’s emissaries and reporters of her progress.

Low in the eastern sky

Is set thy glancing eye;

And though its gracious light

Ne’er riseth to my sight,

Yet every star that climbs