Erica Lagalisse

On Anarchist Anthropology

Erica Lagalisse is a political anthropologist, heteronymic writer, and the author of “Occult Features of Anarchism” (2019). www.lagalisse.net

See the special issue edited by Matteo Aria and Andrea Buchetti in the Rivista di antropologia contemporanea, Issue 1/2024 (January-June) (www.rivisteweb.it) for further discussion of “imagination” in the work of David Graeber, and also Lagalisse’s recent article discussed in the lecture, “On Authenticity: Intersections of Race and Class in Consensus Process and Beyond”, which may also be downloaded in zine format here: en.scrappycapydistro.info

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V8vBWkgvCOM

Introduction

Camilla: Thank you very much everybody for coming. It’s lovely to see this room all filled and also the Zoom room I think is really filled. Tonight is going to be a very special occasion on anarchist anthropology and we’re here with Erica Legalise who’s prepared some special media for us. But I’m going to hand over first to our own resident. Well, is he an anarchist anthropologist, Chris Knight? He’s an anarchist, he’s a communist, he’s a lunarchist, which is what we favour most of all. But we have been involved with some pretty anarchist shenanigans, including, what, the assault on the Bank of England, April Song’s Day of 2009, et cetera. Chris, do you want to comment?

Chris: Yes. Well, as you get older and older, especially as you get in your 80s, you begin to feel that you’ve learned a few things in your life and you read a few books and you’re not going to come across one tiny little book which is going to change your perspective on the whole of the history of Western Europe. Now, there’s an exception. Because when I read this book, I was just Absolutely astonished. Every page, there’s an eye. And I just got no idea about all this. I mean, I’d got no idea, for example, that when Marx and Engels established Comics International, the only organization around in Europe capable of making it all work with the Freemasons. The first meeting of the Communists International was at a Freemasons Hall. I mean, that’s just one little snippet. This is the only book of Erica’s I’ve read, and I’m ashamed to say that. I really need to read so much more that she’s written. I won’t say very much except that Erica is not an Oxford don. She will not be standing limply before you, eyes cast out, nutting from an obscure text. Erica is just an astonishing speaker. She lives reads, leads, cries, shouts, laughs, everything she says. And I’m looking forward enormously to hearing about, well, about the, about anarchist anthropology, but perhaps even more excitingly, the anthropology of anarchism. Erica mixes those two things up beautifully, deliberately, and it’s such a fizz when she does this kind of thing. Over to you, Erica.

Lecture Preamble

Erica: Thank you, Chris. That’s a great introduction. I love that introduction. I’m now in train. Okay. So, so thank you for the introduction. I know everyone is waiting with unbated breaths of the sequel to the dawn of everything last week, and I will get to that in due course. But first I’m going to talk about my own work, which Chris has just so generously introduced. I’m going to approach the topic of anarchist anthropology by doing an anthropology of anarchism. This is the dialectic that I have to offer my best conversation with anarchist anthropology. Context, I study anarchist social movements, so I’m a political anthropologist that does social movements ethnography, not hunter-gatherers, for example. This means I study anarchism as cultural production I do also use anarchist theory and thinking to do anthropology. And I think that’s a valid project. But I also at the same time, you know, make sure to study anarchism itself as cultural production now and throughout history, which is what I was doing in this book, which I’ll summarize in part today. That is... Thank you so much. So they call features of anarchism led to a materialist analysis of anarchism. Are there doing people seeing the stream through the camera or are they seeing it through differently? Okay, so I don’t need to worry about the camera on the screen. Okay, sorry, thank you. So yeah, I do a materialist analysis of anarchism, but also an anarchist analysis of Marxism. and a feminist analysis of both. There’s lots of triangles in the book. And today I very much abbreviate the historical and analytical expositions in the book to come quickly to its final commentary, both generous and critical about anarchist anthropology. Before I begin, I also want to bring our attention to anarchist anthropology in relation to questions of form and political engagements in ethnographic writing as method, as well as research method or theoretical frameworks, and how these work in dialectic in Mayan public anthropology, where I purposefully speak nearby, to borrow a phrase from anthropologist and filmmaker Nitrin Minha. cultivating like specific texts in dialectic with particular audiences, consciously playing with voice and heteroglossal alia as pedagogical method. And so it is purposely that I bring you a version with the occult features book talk that I that was developed for a feminist anarchist squad in Greece and later adapted for the witches are back festival in Rome just now. I think now about how this text that I’m about to deliver is about, is meant to be read a paragraph at a time, okay, with a somewhat bilingual crowd listening, getting to hear it in English, then in Italian or Greek, then in my language, then in their language again, which is a particular kind of rhythm and trance and gives everyone twice the amount of time to absorb what I’m saying in this pretty fast moving abbreviated condensed book summary. which is a benefit that you guys don’t get tonight, so stay sharp. If I’m good, without translation, I’m hoping this will be 30 minutes. And then we can have, well, then the idea was that we’d have a bit of a chat, and then I would have like, I have like a 25 minute stick in response to last week’s lecture that we definitely want to keep space for. At this point, I might like, Given how we started, I might just run into the whole thing and it might be like you, Camilla, and just take up the whole time talking and you’ll have to forgive me and asking all the skill testing questions in the pub. Well, I’ll try, but I’ll try, but... Yeah, enough, enough meta-commentary.

So this is the ethnographic context where I delivered the text last weekend:

You’ll see I’m not using PowerPoint in the Forte Plenestino in Rome. This is my Italian book translator and Edward who is doing running translation. I will proceed to show you slides today.

These slides being the backdrop that I do use sometimes, like at these big production psy-trance festivals, where you have this sort of TED Talk type infrastructure:

You’ll notice this lot of slides have pictures and not text, because I don’t just write about the art of memory. I do try to practice it. I also apologize for using my papers. There was a time between 2019 and 2022 when I basically had this thing memorized, because I did it every week. But thankfully, I’m out of practice. So this is where it starts.

Lecture Begins

Tonight I want to focus on how when I first started looking into the New Age movement and revolutionary fraternities that helped generate modern anarchism and socialism, it was not because I was fascinated with the Illuminati or debunking stories about it. was because I was an anarchist militant myself in Montreal and later studied in anthropology my own activism our campaigns in support of indigenous people, the admits in Canada and Mexico. In my first academic article, for example, I present Magdalena from Mexico on her speaking tour in Montreal, and I describe how anarchist audiences seem to have trouble understanding her as political because her activism, which involved campaigns to resist sterilization among indigenous women, was somehow not seen as political as roadblocks or reunion movements. And they also had trouble understanding her as political because she used spiritual and religious language to talk about her true politics, referring to the creator and mixing both indigenous and popular Catholic spiritual and religious references, with both of these seeming to work to depoliticize her in different ways. And I wanted to show that this wasn’t a coincidence, that the public-private divide as applied to religion and politics and to the domestic and the political is one and the same. I explored the creation of this dichotomy in colonial history, where religion is projected onto the colonial subject in the same gesture that it is gendered as irrational vis-a-vis the secular rationality of Western political men. The construction of politics as distinct from everyday life in general was always an artifice of the patriarchal modern state. To honor any public sphere of politics, vis-a-vis a private or non-political sphere, was to operate according to state logic. The idea of anarchist autonomy adapts the aspiration of state sovereignty. Anyway, the response to this first article about Magdalena was, you know, everyone agreed, Yes, we should pay more attention to gender. Like just, and regarding anarchist atheism, they said, yes, we should be more respectful of indigenous identity. And this last really bothered me because I thought I had made it quite clear that the problem goes much beyond a failure to be polite in the presence and difference, as the point is about the radical imaginary in general. So I’d have to try again. I’d have to try and get anarchists to understand that they have a cosmology too, however much they may be inclined to mystify the theology of their own politics in supposedly secular categories, including history itself. I thought, I need to get people to understand that anarchism itself is cultural production. It’s man-made stuff. And then and now, I have also been interested in studying stateless societies to learn about power, using anarchism to think anthropology. David’s fragments of an anarchist anthropology was enormously inspiring. But it was ethnographic fieldwork experience itself, such as this experience of Magdalena on the tour and so much more, that my studies in anarchist anthropology did shift to start to include studies in the anthropology of anarchism. So A cult beaches of anarchism is the product of this. It happens because I go back to the library in an effort to turn to history to explain the logical connection between the racism and the sexism in some of these anarchist spaces that marginalize the indigenous women’s political subjectivity. And it was only in the process of that inquiry with those modems and that ethnographic departure that I discovered that any inquiry into the cosmology of the revolutionary left, the modern revolutionary left involves stumbling into, you know, Freemasonry and other clandestine fraternities and guys in secret clubs dressing up as Egyptians and all kinds of shit like this. And because during the decade that I write the book, the question of conspiracy theory becomes increasingly problematic and divisive on the left itself, I decide to do a trick of popular education and a sort of word magic. And I cited as the leader of the Illuminati. And the last couple of years have been sort of interesting. It had a life even greater than I imagined. It just keeps. rolling around the world doing all kinds of stuff. But today, as I say, I spent the pandemic talking about conspiracy theory in this book, right? But today I want to focus, as I say, on the gendered and racialized construction of the anarchist revolutionary subject. So the high tag, that’s where it is. Okay. So the book, because so now I’m going to kind of like I’m going to run through the historical exposition of the book, like And if anyone, I really want this to be like a midnight gospel podcast. It’s a guy from Adventure Time, like illustrating it. Like, can you just picture that? Like, you know, now that I’ve said it, if you know, I love this. So the book begins in early modern Europe, when social movements challenged power in Christian language. At some point, their form changes from that of the from that of the millenarian movements, which were spurred on by a charismatic individual, to heretical movements with organizational structures and programs for change. What happened? Partly this had to do with non-Christian mystical doctrines that began circulating in Europe during the Crusades. Platonic philosophy, Pythagorean geometry, Islamic mathematics, Jewish mystical texts and Hermetic treatises were all rediscovered during the Renaissance, which led to the Enlightenment. With this composite also led to new leveling projects from below. Take the Hermetica, a collection of texts written in the 1st or 2nd centuries AD, but which during the Renaissance were held to be from ancient Egypt and given special attention. The Hermetica beholds a cosmic time characterized by emanation and return, where man is a microcosm of the universe, as above, so below. The cosmos splits in twos and threes as it unfolds in space and time, with a web of hidden correspondences and energies cutting across and unifying all levels. But in duration, everything still remains internally related, like all is 1. Importantly, in relation to the history of the modern left, humanity is understood to participate in the regeneration of cosmic unity, and our coming to consciousness of this divine role is a crucial step in that process. So God and creation are imagined to be one and the same, with the slip that our creative and intellectual power is also divine. Yet the initiate must purge himself of false knowledge in order to be able to receive the true doctrine. So Hermes keeps the meaning of his words concealed from those who are not ready. So this collection of materials is very adaptable. It’s metaphysical geometry that arrives alongside the tools of algebra and the Pythagorean theorem. helped encourage an investment in mathematics, right? Mathematics, which becomes the hidden architecture of the cosmos. And these ancient secrets, they did permit an ability to build and create in ways never before imagined, right? Providing both the vaulted cathedrals and calculus for itself. So that’s very powerful magic, right? The combination of pre-existing natural philosophy, the Hermetica, the classical art of memory, this is how we get alchemy, Rosicrucianism, vitalism, all of which behold secret cosmic correspondences and sacred geometry, which in turn inspired the scientific revolution of the Enlightenment. The concepts in Newton’s physics, attraction, repulsion, these are adopted from Hermeticists, for example. These ideas are contained in modern science as well as today’s New Age movements, and also other proceed to explain in secular, anarchist, and Marxist theories of social change. We come to understand throughout the exposition how the disenchantment tale of the Enlightenment is just a tale. The persecution of magic and witches served to enforce the logic of private property and the transformation of women into producers of labour along the lines drawn by Federici, who here knows Soviet Federici’s Caliban and Ilchbach, or K at least half of us, akin of the town. The point is, at the same time as you have these guys burning witches, they have court magicians, okay? So it’s not magic, that’s the problem, it’s who was doing it and what. So the Hermetica also influences, you know, social movements against systemic power as well as dominant high culture. It also influences social movements against systemic power, including Freemasonry. Now these social movements are decisively masculine. Women’s status within the heretic movements was always ambiguous, but they were there. Freemasonry is what social movements look like after the witch hunts. Just as alchemists played the creation of life while the state worked to steal feminine control over biological creation by hunting witches, speculative masonry emerges in which elite males worship a deified grand architect upon the ashes of actual artisans’ guilds while real builders were starving. Now, the trade secrets of operative masons gradually become the spiritual secrets of speculative ones, with large membership being replaced by literate men, lured by the ceremony, ritual, and a secret magical history supposedly dating back to the time of King Solomon and the architect of his temple, Iramabit. Now, one of thematic aspect of the Masonic cosmology that is key here is the notion that man and society tend toward perfection. The idea of cosmic regeneration combined with A new faith in scientific progress encourages perception of worldly institutions as permanent and ones through which fantasies of progress can be enacted. So a new heaven on earth would be manifest, but through the works of men themselves, we do mean men, luminary men, maces, you know, imagine themselves the creators of a new egalitarian social order and protagonists of cosmic regeneration all at once, all articulated in the language of sacred architecture. There’s a society who’s sort of anti-clerical, but also espouses a kind of pantheism that infuses the leveling project with sacred purpose. Now, masons, they did also include privileged men who used the lodges to consolidate their power, but at the same time, the Masonic ideal of merit as the only just distinction allows room to critique internal contradictions. So in France, lodges begin accepting workers, they abolish the literacy requirement, So by the time of the French Revolution, there’s up to about 50,000 members and 600 lodges. And this is where we arrive at the question of the conspiratorial secret societies that’s become so sensationally exploited. Am I speaking too fast? Am I okay? That’s all right? Okay. I’ve tried to practice over time, you know, speaking, also often speaking to second language audiences, like just pronounce my words. But I know sometimes I blur things together. Without meaning to. So, okay. This is all just suspense, but the secret society. Okay. So, yeah. So, some Masons were revolutionaries. Yes. Okay. Other revolutionaries were not Masons, but they make use of the lodges infrastructure and social networks to further their cause. Yes, that also happened. Three, yet others just adopt the Masonic iconography and organizational style when developing their own completely separate associations because these are the ones that have accrued a certain symbolic power and legitimacy. And it’s not really possible to distinguish entirely between these phenomenon in retrospect, nor is it important in my view. The important point being that the revolutionary brotherhoods at the turn of the 19th century derived power from a collective self-association with perennial secrets and magical power, and that their related style of organization informs the development of what we come to recognize as modern revolution of them. And I won’t reproduce the whole story of the Illuminati here. You got to read the book, which we conveniently have for sale. But it was basically started by a profess in Bavaria in 1776 who wants to dismantle the state and church, but also the institution of private property, inheritance, which was particularly radical for the time. He’s still particularly radical. And if you tell my middle class radical friends to share their inheritance, they get like, they feel on stage, I think. But yeah, so they’ll just, you know, so he’s a particularly radical guy. And he elaborates all of this with a reference, you know, the mix of Rousseau and the Eleusinian mysteries and the secret association of the Pythagorean. It’s all in there. Now these profs and students, they grow, they join Masonic lodges, to radicalize what we would now call liberals into their movement. And the pyramid structure of the network, which is modeled on Masonic form, it works to transmit and enlighten ideas that are quite commonplace now, like the value of science, as well as ideas about the utopian regeneration of society. Eventually, someone snitches to the Bavarian royal family and a repressive campaign begins. And this is the first time we hear that all Freemasons are under the control of the Illuminati. Except at this time, the idea was that the Illuminati were revolutionaries conspiring against the government. And later on, we can discuss on why the story got turned around. in the 5 minutes we have for a discussion. I’m sorry. It’s in the book. Afterward, okay, after this repressive campaign, members go into hiding or exile. And yes, more new, similar revolutionary societies appear across Europe. It made sense to organize in a clandestine fashion because following the French Revolution, the dynasties of Europe, they formed the Holy Alliance. and they proceed to cooperate in international surveillance of oppression in an organized way for the first time. So partly, the pyramid structure, which you only know your immediate superiors, was practical because it protected you from snitching if you were caught, tortured. So that’s one very important point. But also the ritualistic aspects of the brotherhoods, they affirmed and unified the aspirations of men who understood themselves as illuminated and having a special purpose of steering mankind toward achieving perfection on this earth. Bakunin was a mason himself. He founded his own international brotherhood that mirrored the Illuminati in many ways a hundred years later. One indifference is that Bakunin’s brotherhood was meant to infiltrate the First International and arrested for Marxist control, as opposed to infiltrate Masonic lodges in order to arrest them from liberals control. In some ways, that’s entirely different, or in some way, that’s not. Communist and anarchist symbolism such as the red star and the Circle A, illustrate this genealogy. The star, as esoteric meanings at both the Hermetic Pythagorean traditions, was adopted in the 18th century by Freemasons to symbolize the second degree of membership, comrade, and was later adopted by the First Internascina. Early versions of the Circle A are clearly composed of the compass, level, and thumb line of the Masonic iconography, arranged to form the letter A inside of a circle, the dawn chavier. And many anarchists today, they may not know that the star used by the Zapatistas, for example, is a pentagram, or that the Illuminati was founded on May Day because it was already a special day before the Haymarket Massacre. But in the 19th century, these associations were more well known. At the time, the main people involved in the revolutionary scene who were annoyed by this sort of mysticism were Marx and Engels. Now, Marx And Bakunin, of course, differed on a number of points, the most famous being the role of the state. Whereas Marx considered a state dictatorship to be a necessary moment in his dialectic, Bakunin promoted a secret organization that would “help the people toward self-determination without the least interference from any sort of domination, even if it be temporary or transitional”. Yet at the same time, he saw “our only salvation in a revolutionary anarchy directed by a secret collective force.” Gotta love this guy. I feel like I’ve met this guy so many times. That’s also sorry. Okay, the quote continues. “We must direct the people as invisible pilots, not by means of any visible power, but rather through a dictatorship without ostentation, without titles, without official right, which, in not having the appearance of power, will therefore be more power.”

Chris: Scumbag.

Erica: Well, I mean, you know, he wasn’t all bad. It was. But you can see where some people like, you know, start misunderstanding.

All of this only represents a paradox if we don’t recognize the tradition and cosmology in which Flacun and his work. Okay. Revolution may be imminent in the people, but the guidance of illuminated men working in the occult is always necessary to guide them in the right direction.

Beyond Bakunin, I’m speeding through a lot, but the lefties involved in the spirituality of the new age and the occult revival at this time are endless. I address the Owenites, the early feminist Ani Pestard that you schooled me on earlier. Adrenaline. She gets credit for a lot of other stuff Arkansas men did, apparently, it doesn’t surprise me at all. Tolstoy, We talk about how anarchists of the 19th century were into the theosophy of Blavatsky, there’s a section on Darwin, and certainly the influence of thinking when playing with the idea of evolution and revolution. Charles Fourier, who based his political project of what he called the law of passion and attraction, a series of correspondences in nature that maintained harmony in the universe and applied to human society. Because I did my research in Mexico, I also happened to, I went down that rabbit hole, and I know that the first European anarchist in Mexico distributed pamphlets on pantheism, about theismo. Sandino, who later became the icon of the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua, was enthralled by theosophy. He was kicked out of the Third International for flying a rainbow flag with weird spiritual symbol on it, a stylist, run into that, you know, and these, I write through all this really quickly now, without specificity, the all these colonial encounters, okay? In the book, he explored in more detail how the cosmological fusion underlying modern revolutionism keeps going and perhaps finds only its latest expression in present-day anarchist selective fascination with indigenous cultures and cosmologies. In 1902, C.L. James wrote, Scratch a spiritualist and you’ll find an anarchist And it was the American Association of Spiritualist that first published the Communist Manifesto in America. And we can imagine how much that is a lot, Marx. You know, the poor guy, he’s like, he’s like Tesla now, like, rolling his grave, like, Hi, but you know, but Marx’s anticipation of a communist era brought out, brought about by a mixture of will and cosmic fate is itself pretty new age. I mean, that’s a part of that same eschatology. The major difference, you know, that makes Marx’s vision scientific compared to the others was his theorization of the dialectic. And I really, I love dialectics. So again, there’s more of that in the book. But basically, Hegel’s dialectic casts history as a dynamic manifestation of the idea, right? the unfolding of consciousness itself, in which everything is an attribute of a single universal substance. Hegel is a hermeticist, while Hegel is obsessed with emanation and return by weight of neat geometrical constructions of all kinds. The idea issues in nature, which issues in spirit, which returns to idea in the form of absolute spirit, and so on. And of course, Marx famously breaks from Hegel in that consciousness is understood to follow from material relations. But his historical dialectic, both transcends and... contains Christian and Hermetic eschatology as much as Hegel’s does. So one important synthesis here is that socialism and occultism develop in complementary fashion during the 19th century. Just as Newton’s alchemy is largely ignored, so Fourier’s law of passional attraction is rewritten in mainstream histories of the left as a vision of, quote, a harmonious society based on the free play of passions. Right? I think that was Peter Marshall. No, with all due respect, I mean, to the Marxist history, I think that is not wrong and straighten me down. As Marxist scientific socialism comes to dominate during the 20th century for all the complex reasons that it did, the spiritual aspect of modern revolutionism becomes occulted. And occult philosophy becomes caste as discomforting and anxiety provoking periods of social change. For Adorno, occultism is both the primitive holdover and a consequence of commodity fetishism at once, in a typical circular and colonialist argument that suggests that the occult worldview is wrong because it’s animistic and vice versa, like a regression to magical thinking. Over and over, we see interest in the occult portray as either inducing apathy among the masses, whereas the territory of the elite reactionaries, the use of Blabatist theosophy among fascists and eugenesis is often pointing to doubt. And it’s true those connections are there. And it’s true that launching this book in 2024 versus 2019 is really different and like really dark. Like this was meant as a sort of cautionary tale. And like right now it’s like an autopsy. Yeah. And it’s quite scary. And to learn the fascism thing, you know, really good before it. Hang on. When considering the relationship of magic to anti-systemic movements, and this was my, this was my call time. This is my cautionary tales. Like any... When considering the relationship of magic to anti-systemic movements, any deterministic formula is bound to fail. When approached by privileged persons with a lust for power, magic can justify and advance elite aspiration. But without the influx of so much material charged as ancient magical wisdom that helped triangulate popular religion, modern materialism with social discontent in new ways. We may never have seen the rise of modern socialism and anarchism as we have come to know them. Oh, I love the time check situation. Okay. Another important point. No, because I want to do this to this feminist part. I mean, enough. Come. The important point is about... That’s one summary point about that magic from the left and right. Another important point is about identity and property. When I first wrote about Magdalena being excluded in her own speaking to her 10 years ago, gosh, 20 years ago now, I kept getting this response like, oh yeah, like I said, it’s important to respect indigenous identity. No. The idea is that when entire cosmologies are reified as proper, only to specific identities, we’re effectively saying their fault, to the extent that they don’t apply across the cosmos whatsoever. So the sacred is thus rendered nothing more than a cultural property in a marketplace as big as the universe. Now, appropriating indigenous spiritual forms without the intended content is entirely in line with the logic of capitalist colonialism. Cultural appropriation, okay, is a thing and it’s a problem, but so is marking off and containing everything considered sacred as property and therefore nothing more. So how to navigate this dilemma in the, you know, fraught terrain of social movement. It’s not easy but important to think about. I’m I’m looking at you in Montreal Anarchist Book Fair. Cheats. Others, if you know, you know. Other important questions to ask. Okay, here we go. When anarchists read about sovereignty, why do they read Agamben and Schmidt? while saying they want to take lead from the Global South. If they read indigenous women on the topic, they would have to realize that European sovereignty is always involved subsuming women and children as property of male citizens, whereas it is specifically male citizens that are subsumed by the sovereign. And that the male philosophy slip between legal person and human being is preserved in the anarchist response, autonomy. Autonomy being the idea being constructed A dialectic with the state. where the anarchist person is imagined as an independent, autonomous, and transcendent, sovereign being that enters into mutual aid with others of its kind, just like the state, maybe. And just as the state characterizes itself as benevolent to its citizens, the anarchist considers himself benevolent to the people, women, similarly subsumed in his autonomy, and without him, he could not survive. So to simply argue now that real anarchism is by definition feminist insofar as anarchism is theoretically against all forms of definition is an important move, but it doesn’t engage how the anarchist revolutionary person was constructed vis-a-vis a variety of exclusions from the outset. Revolution may be imminent in the peoples. But as anyone can see, fluency in a particular vocabulary, knowing certain names, having the right contact, is all a requirement for entry into the anarchist club, as is a commitment to a specific ideology informed by the history of its practice, where men’s oppression by the state becomes a sort of prototype for power in general. And, you know, I realize I am forcing analogies a little bit. I, you know, I force an analogy by saying that the social and subcultural capital that I’m talking about now is just like the code words of an Asiatic societies in the 19th century. But, you know, at the same time, the hidden correspondence is worth reflecting on. I don’t know. So the fact that anarchism may be against all hierarchy as an ideal, but anarchist activists and intellectuals highlight power in some places more than others, such as the state. Studying anarchism anthropologically means accepting that anarchism itself is a cultural and historical phenomenon invented by particular men with particular political priorities in a particular time and place, with its theory of practice being influenced by power relations among anarchists themselves. And this doesn’t mean that It doesn’t mean that charting examples of anarchy throughout the colonial record or indigenous societies is not a valid political project or thought experiment or a valid way of doing anthropology. It’s just important to also chart the emergence of anarchism as a distinct ism as well, you know, to keep ourselves honest as we proceed. Carl Levy has always been a really important mentor in this regard. And And then yet, and this is just, to any interest of making a project of anarchism as non-hierarchical as possible. It’s important, like within the project of anarchism, not a gate stitch, so to speak. So if scholars like David, you know, or James Scott or have provided us with some great fragments of anarchist anthropology, I come back with the anthropology of anarchism just as part of that project. The dialectic is dead, long dialectic. At least I think I’m going to leave it there for now. It’s basically where I was going to end anyway. At the witches are back, I kind of ended with a thing about how there’s some other things I could say now in 2024 about the secret society, about the power of the occult. And here, I mean, not magic, but organizing in the occult as opposed to on the internet and other thoughts about practical challenges facing social movements today and how this book can be useful in whole new ways in 2025. But But, yeah. I’m going to end there for now. That’s what, and then when I always send out a e-mail sign-up sheet, I finish by saying that and I say, oh, and by the way, fuck fascist social media and algorithms, Zuckerberg and all that stuff, but let’s join my CC list if you want to hear more. I’m going to take this pace of tafer and I put it here and I try to remember to get it later. And if I’m with anarchists, that I usually have on the other side, my own contact info. And I say, oh, if you’re an anarchist and you don’t want to put your contact info on your sheet in public in an event, you can just take a photo of mine instead. There’s a whole shtick about that. But okay, I’m going to stop.

Audience Questions

Erica: The thing that I want to do about The Dawn of Everything is about half an hour. So that means you’ve got 10 minutes to ask me everything you’ve ever wanted to know about the Hermetica, feminism, anarchism, and the Illuminati. Let’s go.

Audience member #1: What was the process of creation? Like, this is the final product, but what is some of the mess of the writing process behind the book? And how do you cut something down?

Erica: I kind of love this question, by the way. Thank you. I just, this gives me a chance to humble brag, for example, that this book is chapter 3 of my PhD dissertation. So there’s quite a bit out of frame. And it does, in a way, I’m flattered and in a way I’m infuriated that in the past five years, all I’ve gotten to do is talk about chapter three of my PhD dissertation. Was everyone thinking that it is the PhD dissertation, which I suppose I could take as a compliment, but also I kind of want to finish my disk book. So yes, and I think the other, one way of putting that in different words is that any given text thing book you write, especially when it’s not like a PhD thesis is meant for you and your supervisor, like something between you and your God, you know, like you’re figuring out something for yourself. Like if you’re going to write a book. It’s not, it’s never, the point is never to encapsulate everything you know about everything because it does. That, especially as you get older, I mean, that goes off in every direction. A book is a particular object that’s directed to a particular audience that’s released at a particular moment in time that particular people that you imagine are going to read it, plus other ones you never thought about. But, you know, and so you, this book is like an intervention at a particular time in social movements to try and engender specific conversations. I wanted to let the anarchist understand that being exclusive and practicing a politics of distinction around conspiracy theory and keeping like the space like safe from anything that might sound like that, like in a way made sense, it was understandable, but also There’s a whole bunch of people that are like leaning towards these theories of power and interpretations of history. And if we just ignore it and kind of like keep them upside of the social open space, the result could be bad. You know, they might help. Anyway, we’ve been around, whatever. Witness what happened in the pandem with conspiracy theory and the laughter and everybody don’t even know. I was worried. So And I was trying to do a thing where I wrote a book that was sort of had a certain import to intersectional feminism and like, anarchists who, proper do with proper leftist political analysis. And I’m also, but the book is also interesting to people who are just interested in conspiracy theory, looking for something like solid that they can actually read to like get a handle on what they’re seeing on the internet. And it’s like well cited, because it really is. And in the process, I want to make a book that would get like conspiracy theory guys and feminists and anarchists in the same room, like in work. And I had no idea what to do with them. And it was very weird being in some of these bookshops. But anyways, I got to get a fun probably, but like, You won’t write only one thing in your life. Just you got to cut stuff out and not be worried about letting it go because you can write that elsewhere later. You know what I mean? Like any given text you write, it’s just that text. And there’s always like so much more different. And one more thing I’ll say actually about the book club, because this happened in the book club last week. There was like every time, all the time, when I present this book, there’s inevitably some people in the audience, usually men who are like, So I know something about this topic that wasn’t in your book, right? No idea, what I mean, right? And then it’s like, so you didn’t mention this bit, and it’s like they’re telling me like this thing about, the Scottish Rite or the Correspondence Society or something like, it’s like... And he said, gosh, how much, how much you need to know about all that stuff in order to write a good book about it this fucking long? You need to know so much. I need to read like 2,000 books, like this big, like in three languages to be able to write that book. If those little details are not in it, it’s not because I don’t know. It’s because it didn’t make sense to put in that synthetic little prism of a book. There, that’s my defense. Okay, one or two more questions.

Camilla: Is there anyone on Zoom would like to ask questions? Like somebody who wants to send an e-mail to the contact list if we have it.

Erica: Oh yes, in fact, please, I want, I meant to specifically invite anyone, all the people on Zoom to likewise share their emails. They can do that in the Zoom chat if they feel comfortable or they can e-mail me, like just write to me, put my website in the Zoom chat, like at lagalese.net or my e-mail is in that website. Send me an e-mail and I’ll put you on the list.

Camilla: Mary writes: “You wrote mathematics became hidden architecture of the cosmos, the most permanent and basic truth. Is it the reason why, in your opinion, Mathematics are a prominent subject at school?

Erica: Mathematics is incredibly powerful magic and science. So, of course, the answer is yes.

Chris: I just wanted to say something really, which is certainly reading this book, it’s absolutely extraordinary how you managed to put it all together. It is kind of a whole history of Western European thought and activism and everything else. Absolutely amazing. And I’m the last person to think, oh, you didn’t mention these or you didn’t mention those. I suppose the political issue is I mean, we are, I mean, the challenge of our time now, isn’t it, is to be able somehow to pass on to future generations a habitable planet. And I can’t help thinking of climate science and why we believe in it. And this, no, I’m not saying you should put this to the book. No, worth the reason why you should put climate science in your book. It’s just that there’s One possible contreason for me book is that somehow science is always a version of the occult. And for me, there’s nothing more collectivist, accountable, anarchist, international, internationalist than ordinary science at its best. Because we wouldn’t even know that when you drive a car or smoke a cigarette for like a bonfire, you’re, you know, you’re putting up CO2 in the atmosphere and it’s potentially causing catastrophic global warming. I’m just saying science is anarchism. At its best, anarchist knowledge in the sense that it’s always bottom up. You can’t have a guru telling people what to think. It never works because the scientific collective is always trying to pull everyone down. It’s talent leveling. Somehow that doesn’t get recognized as anarchism. But for me, it is. It’s anarchist thought is at its best in genuine science. That’s no reason why you should have said that in this book, Erica. It’s just that without something...

Erica: I think I know what you mean in the sense that, I’m a scholar, like in the peer review and it’s most romantic, you know, what it’s supposed to be is the great way of pursuing collective laws. So we don’t have the reinventing of the wheel or two people spinning the wheel. You know, we, the experts, can review each other’s work and you end up with something. I mean, like that is the academy and I am into it. Now, the actual functioning of the academy, the, you know, everything from Latour to my own personal inbox, I mean, it’s just... the way things actually get produced, the editorial world, destruction of power, the classic, the neoliberal metrics, the ref. I mean, I never thought I was supposed.

Chris: Science was making a mark about 20 years ago. You did have the oil companies managing to produce fake science, including on Channel 4, you know, the climate, the climate science hoax and all that. And somehow that has essentially gone. And there is such a thing as the science of life on Earth, climate, and everything else. And in order now to sort of say, I don’t care, Donald Trump, Elon Musk, and all these people are just going to say, sack the scientists, get rid of the scientists, get rid of them. So that’s a change. And it just seems to me so critical now to be not just kind of on the side of science, but to be with scientists in solidarity, writing gender and egalitarian sites to become had to acquire its own politics. That would be energies, I would remind you, because the state can never do science, because the state’s always got its own nationalist priority. Whereas scientists, particularly the obvious example is climate science, but there’s so many others. Yeah, obviously medicine, health and everything else, and I think it comes to a circle, they’re saying generally scientists. Deep down, they, I don’t think they do care about which country they come from, which religion they have. I think genuine scientists generally are if you like collective of anarchists in that sense, you know?

Erica: Like financiers (laughs).

Chris: I mean, come on.

Erica: No, yes.

Audiance member #1: Yeah. I don’t know if you’re going to go to the second-half of your book now, which I don’t want to kind of, We’re changing your direction completely. You talk about, yeah, you know, that really almost like a hierarchy of kind of social theory and the way in which conspiracy theory does in a way begins to kind of kind of go against, you know, you go on about talk about the code, for instance, and you talk about the kind of meta narratives or modes of kind of Marxist theory, how conspiracy theories of really the map might be the man in the street actually starting to think about how societies get tracted, et cetera. You know, are we now living, now that the book is really interesting to see it now and see what’s going on in the world, are we living not only in a post-truth society, but a post-conspiracy theory society, that now the conspiracy theories themselves perhaps have become the kind of like the narrative and becoming a sense kind of theory and, you know, where do we go from here? And in a bigger question, how do we as kind of intellectuals, what are we doing?

Erica: I see a project in the works.

Audiance member #1: Yes, I know.

Erica: I really like it. So, you bring up that there’s a whole discussion in the last chapter of the book about an anthropological study of conspiracy theory to category. And that’s an, that’s something that’s out of frame here. That’s part of our mimetic archive. And he’s asking me like, how, you know, what do we, what would it look like to think with those ideas now, to think through the present moment? In 2016, I’m writing Trump’s first ascent to power and conspiracy theory occupies a certain, slot. And now in some ways, it’s become more vilified, but it’s also become more normalized. And what would we need to think through all the same stuff now? I hope I did okay with that.

I’m going to respond in a really abbreviated way. To Chris, your thing about science and magic in the occult, let me just say I really recommend anyone who wants to think about the history of science and magic and how they’re connected and But the book that really informed me when I was doing this, which is a great, great book in anthropological theory, is called Stanley Tambaya’s Magic, Science, Religoin and the Scope of Rationality. It’s A Henry Morgan lecture, I think, turned into a book, I believe. It’s very, very good stuff. And then also I wrote a piece called ‘Was Marx A Conspiracy Theorist?’ That’s on my bibliography on my website that’s relevant to that question. And I also wrote a conference paper called ‘The Conspiracy Theory as Antidote to Foucault’, which is cool.

Audiance member #2: One of the issues about science is the subversion of science method as a consequence of changes in science publishing and funding, which occurred from the 1970s, and that is actually abusing a huge amount of thought and failures, and it is a major problem. So that’s one part of that. The other thing was going to go on through was that within the West African on what edition, What’s happened, ironworkers were viewed as ritual experts. And so typically when this, when what’s African slaves were in Jamaia, as an example, they were invested with, they were given the respect of ritual actors rather than as artisans. So the tradition was very different to the European tradition of blacksmans.

Erica: If I wasn’t so antsy about getting the other bit of my talk done, I’d like ask you so many interesting questions...

Audiance member #3: This is from Mary. She sent this to me as a personal message, and I thought it should go out to everybody. Erica talks about this French politician, Cruyall. I read that he was the first one to call himself an anarchist. I checked on him. He wrote a book called Courtocris, available online in French. I read a couple of chapters. The things he writes about women are horrendous, just unbelievable. I’m not sure I ever read anything so conservative and idiotic than the anarchy population.

Erica: Thanks, Mary. Thank you for the final exclamation point. Yes, and you know how many anarchist scholars just love the Trudeau and going, there’s some nice things about Trudeau, he’s not old. But yes, thank you for putting a fire point on it. I’d be glad to. And I would say more, but I’m just antsy now. OK, guys, you’re going to have to-- Let me go, because this is, I know I timed. It’s like 25 minutes. I’m already coping you five minutes extra. I want you to see my video. I’ll be here. Let’s get up in it. All right, OK.

The meaning of Monmanéki and his wives

OK, so, and this is the part that directly follows from last week, OK? Chris, this is like my best response to the myth of the--

Chris: Oh, sorry. The story of the Amazonian story, Monmanéki and his wives. They’ve got a key miss in Mythologique’s third volume of...

Erica: For those who missed, who weren’t here last week, you missed the great, great, you know, tour around... Myth analysis.

OK. So what do I have to say about the meaning of the Monmanéki, according to Levi-Strauss, and life, the universe, and The Dawn of Everything? Not that much, but a few things ever so cautiously.

First, I want to thank you, Chris and Camilla, for giving me pride of place last week and handing me the microphone and acknowledging my ethnographic authority, if you will, in certain matters relevant to the work. Well, precisely because of the particularity of my position, I just always want to make sure that I don’t take every microphone that’s handed to me, which is why at one point I very stubbornly stayed in my chair last week. I super appreciated the gesture. But I just-- evolutionary anthropology is not specifically my wheelhouse, nor should I need to sort of pretend it is. It’s not why I’m here, right? Of course not. Right. And I just always-- I get nervous. I need to be careful always about being positioned for or against David’s work, which is heterogeneous, dialogical with different people, internally inconsistent at times. Some of it I like more than the rest, right? I’m a scholar, so my position about one book or another is going to be based on my own scholarly work in that area. And it just-- and I am taking a moment to say that it does seem like a lot of people that I’m interested-- that I meet lately are interested in sort of either pigeonholing me into supporting a kind of simplistic personality cult Or cajoling me into criticizing David as his ex. Not that that’s what you guys are doing, but I’ve had a lot of this. I’ve had a hard time in the past couple of years. And so I just-- and I’m not really interested in doing either of those things. And so I just always rather focus on all the great stuff that I do, honestly, have to say about our intellectual dialogue. For example, it wasn’t about property. It wasn’t about kingship. It wasn’t about hunter-gatherers, but...

Chris: This was the question, how did we get stuck that Erica’s referring to?

Erica: We had a conversation about, I’m going to get to freedom and all that. I’m just putting this up:

Lagalisse, Erica. 2024. “Property and Propriety: An Ethnography of Class and Identity” Historical Materialism Conference, London, UK, Nov. 29, 2024. [long form under review]

Lagalisse, Erica. 2024. “On Authenticity: Intersections of Race and Class in Consensus Process and Beyond.” Rivista di antropología contemporánea 2024 (1).

Thunderstorm, June. 2023. ““Coda”.” In Going for Broke — Living on the Edge in the World’s Richest Country, edited by Alissa Quart and David Wallis. Chicago: Haymarket.

Lagalisse, Erica. 2022. ““Anthropology”.” In The SAGE Handbook of Marxism, edited by Beverley Skeggs, Sara Farris, Alberto Toscano, Svenja Bromberg. London: SAGE.

Lagalisse, Erica. 2020. “The Elvis of Anthropology — A Eulogy for David Graeber.” The Sociological Review [blog].

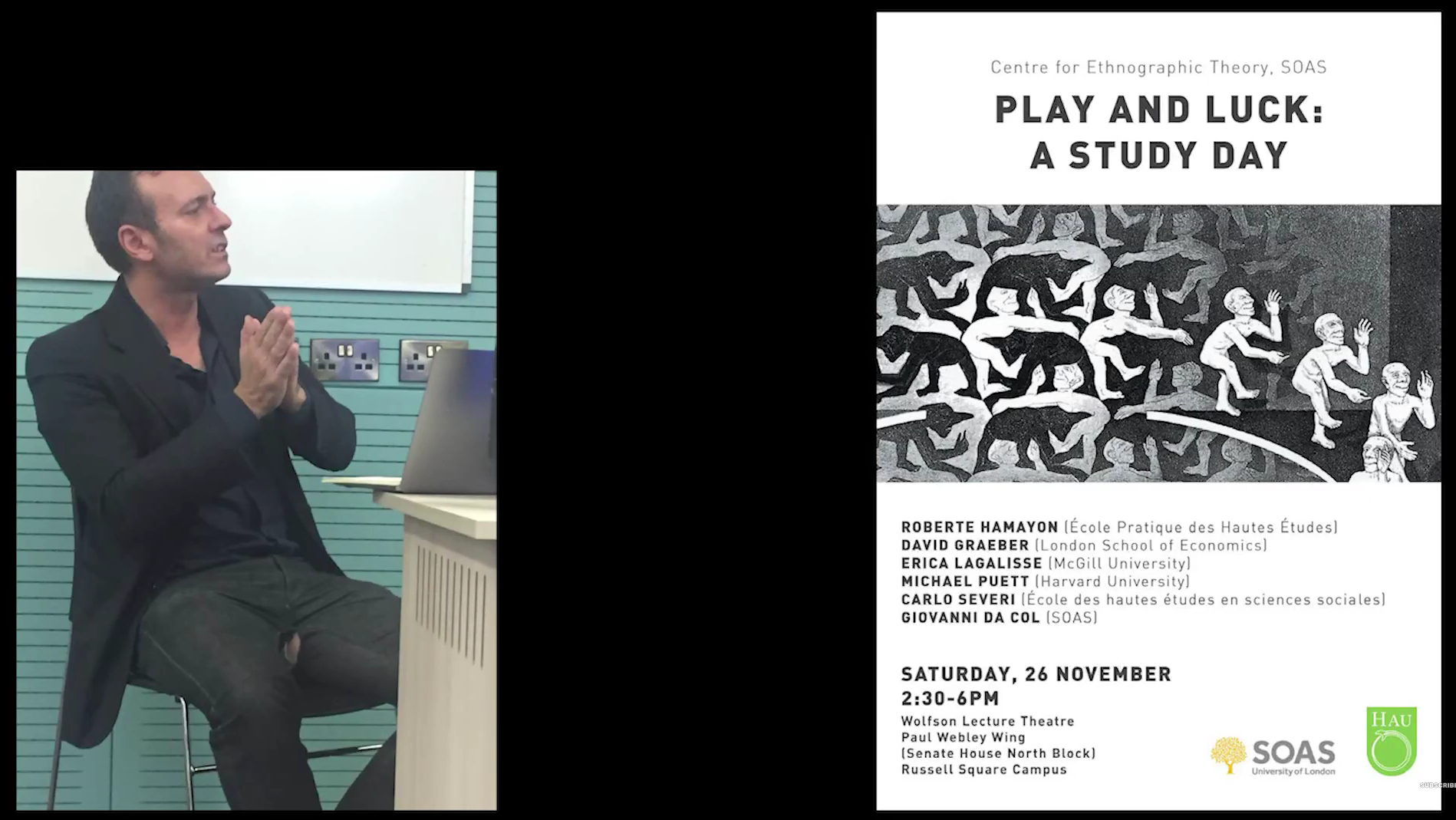

Graeber, David and Erica Lagalisse. 2016. “Manifesto for a Ludic Panpsychism (Why Not).” Play and Luck: A Study Day Centre for Ethnographic Theory (SOAS), November 26, 2016.

Thunderstorm, June. 2016/7. “Revenge of the Mouthbreathers — A Smokers’ Manifesto.” Best American Essays 2017 (Originally published in The Baffler as Off Our Butts (issue 33, 2016) (33).

Graeber, David. 2014. “What’s the Point If We Can’t Have Fun?” The Baffler 24 (24).

This is a lot. But these are just some of the intellectual dialogues that David and I did have. We talked about property, affect, manners. We also had an ongoing dialogue about play, okay? Where the entente, and this is where, you know, I’m gonna leave the other stuff mostly out of frame right now, but... The one thing here that maybe relates best to what we were talking about last week is the dialogue about play, where the entente was whether freedom or creativity is the most fundamental logic of the universe. So David took the position freedom, and I took the position creativity, and we had loads of fun with that. And it was meant to be fun. And that’s the discussion that’s written up in part in the essay, What’s the Point If We’re Not Having Fun? Which I dumped him for that Christmas holiday because I was like, instead of sending me a draft of this thing, which is our conversation, like, instead of sending me a draft as co-authored, you wrote me up as a June thunderstorm sitting in the grass in the first paragraph. And I was just, I was so, I was so upset about this. And so he later granted me co-authorship of that piece. And he did feel, he felt, he’s just used to writing up conversations with people in his bachelor pieces. Like every one of his Baffler articles is a conversation David is having with someone in everyday life for his head. It’s just something he did all the time. He didn’t mean to upset me so much when he did that. He even showed it to me, like, look what I did with our stuff, you know, like I’d be happy. And I’m like, I’m an early career scholar and I’m a woman and I just need this not, doesn’t feel like I’m being honored. So anyway, so later on, to try and kind of heal and fix the scenario, we read another text together called The Manifesto for Ludic Panpsychism that was presented It’s so as. And this text does a lot to show this freedom versus creativity debate that I’m talking about, more so than the baffler piece...

Chris: Did that ever get published?

Erica: It’s not published or found online yet, but maybe we can all eventually fix that.

For now, if you’re interested in more background information, most of this stuff is findable, and I can show you the other three.

This is the event where the manifesto for lunic panpsychism was presented, organized by the illustrious Giovanni de Cole:

This photograph was taken by David at the event itself because what’s the point if we’re not having fun?

So we had lots of conversations about lots of things. We had one about imagination and epistemology, one about dentists-- great conversation about dentists. That’s like a baffler article that never happened. But all kinds of shit.

But I’m not the expert on the divine kingship of the Schillich, OK? I’m not. I found the whole King’s Book era a little tiresome to be age. And I surely misspoke of the Dinka last time because I’m literally mildly triggered by the Dinka.

Thoughts on The Dawn of Everything

As far as early humanity goes, I just don’t know, right? I don’t know. From a disciplinary perspective, and this is going to be like my cautious endorsement of your critique Chris, all right? Where my ethnographic authority best adheres here is perhaps my capacity to say that I don’t entirely trust the material conditions of production of that book. The review process of ‘The Dawn’, the motives of the authors, the ethnographic context of its production is knowledge. Like that’s the ethnographic knowledge that I have that’s relevant, not really about the hunter-gatherers discussed in the book, but about the production of the book.

So does this mean I necessarily am in a position to endorse the theories of RAG entirely instead? Not necessarily, because I haven’t read it all myself, and that’s what I need to do in order to take a position on something, because obviously, I’m always the smartest bitch in the room, and I’m never going to take anyone else’s word for anything.

But, you know, I will. I will. I’ll totally happily humor that the non-orthodox, sometimes ridiculed feminist take that you’ve developed here. Because one thing I do know from my ethnographic experience of the editorial world, and this is in a way follows our discussion about science that just happened, is that it would be entirely plausible that you could have a great empirical set of ethnographic theory, but they would be ignored for bad reasons.

Unfortunately, science isn’t always anarchistic, isn’t always bottom up, and it doesn’t always work.

Chris: But then it’s ideology and politics, it isn’t science.

Erica: Yeah, there’s a lot of that. So, I’m not in a, you know, I’m not in a position to endorse the rag theory of humanity, but I will say it’s probably not to be automatically discounted either. And I do see, you know, what I do see you guys doing and having to do is... because you’re putting forward a theory that is not dominant or easily accepted or invited for a variety of reasons, you are needing to perform science with every step. And you have to be so careful and defend everything you say. And I see how you’re in that position and how not everyone is in that position. And some people can publish what they want much more easily.

So, that’s one apology I’m really happy to contribute.

Something else positive I really want to say about last week’s lecture is like I really want to defend the structuralist bent. I don’t mind apologizing for structuralism in the way that you were playing with it last week and in general. And in view of the critical comment later, you know, the one about binary oppositions that came up, if you were here, you remember.

Chris: You can’t think without binary opposition.

Erica: And yes, and it’s always important to say like, yes, it’s a fair point. And yes, Levi Strauss, he’s annoying in all of the ways that we know about. I mean, I actually did my-- I was remembering when I was doing this. I did my very first class presentation as an undergrad in anthropology. And I did it in the very last class of the semester because I was so nervous to speak in front of public guys. It’s come a long way. My very first class presentation was just raking that guy over for his society being founded in the trafficking of women thing. I just like, you know, so no one needs to remind me about that. But also, you know, let’s not start acting like the appearance of binary oppositions in diverse social systems of meaning comes simply from presuming the brain and world as a computer, you know, as if it’s derived from thinking in ones and zeros as if all mid-century structuralist theory comes entirely from like what, Bateson and cybernetics. I mean, this would also be very reductive. Structuralism and consideration of binaries in myths and ritual architecture, yes, it’s a system of analysis. It’s a map. The map is never the territory. Reality always exceeds. But for example, do we think the vocabulary of spectrums is more ontologically true? That’s what a lot of people who... binaries promote instead as a language of. I’m not just thinking of gender here. There’s lots of spectrums now, but this is a word, you know, this is a word borrowed from modern optics using light waves like as a metaphor kind of thing. And it’s fine as a crafty political metaphor, but let’s just also notice that it’s language, you know? And in this sense, I am thinking in Rodney Needham’s Stoles and Causality. I just, I know, I know I cite this piece in every lecture because I love it so much. Look it up, Rodney Needham’s Skulls and Causality. I guess I don’t have time to go into that anymore right now. But the point is, classical anthropology theory, fine, no problem. Neanderthals, I don’t know. Historical materialism, yes. I do have stuff to say about historical materialism.

Well, this is going to be my almost final point. Touching briefly again on the question of history and freedom. Okay, that came up last week in last week’s discussion.

So, this is just me showing off:

Historical materialism is one of my special interests and areas of expertise. As such, it is like anarchism, a set of theory that I use to do anthropology, but also study critically as cultural production. So historical materialism is historical, right? A man-made set of tools. And in this book, I contributed the anthropology chapter. And I start out by saying,

Marx relied on anthropology in his logical and historical exposition, and anthropology has long existed in dialectic with Marxism. To study anthropology with Marxist categories or subject Marxism to ethnographic scrutiny, it makes sense to proceed chronologically – the importance of history is something anthropologists and Marxists now often agree on. In the process, we consider how philosophical idealism continues to interfere in efforts to build grounded ethnographic theory, yet how ethnography remains a uniquely useful tool to unsettle idealist abstractions that limit Marxist debate itself.

With attention to how ideas about ideology themselves exist in relation to particular material and historical circumstances, I begin by discussing Marx’s treatment of anthropology in his project to historicize capitalism, then how Marxist theory influenced anthropology: by the middle of the twentieth century, the anthropological notion of society was no longer the integrated whole imagined within functionalism, but rather a field characterized by conflict and struggle. Following experiments in material and ecological determinisms, it was feminist and postcolonial revisionings of the ‘class consciousness’ concept that sparked an epistemological debate that informs the politics of ethnography to the present day – insights of the poststructuralist turn may transcend those of Marx, but they also contain them.[1]

And, you know, this, I could go on, like, it’s a whole lecture, but I’m not doing that lecture today, so I’m gonna just kind of put that there as a placeholder, along with the citations I offered earlier, for anyone who wants to just know how much I’ve thought about anarchism and historical materialism together except for me.

The property and propriety paper that was up on the slide earlier is the ultimate take on... It’s what I would really like everyone to see. Unfortunately, it’s been invited and then cut from multiple venues in the past three years in a way possibly explicable by the discussions of semiotic and legal property explored in the text itself.

Conclusion

But Returning to The Dawn of Everything. Yes, it’s idealistic. OK, it is. It’s idealistic in both the kind of pop and philosophical sense. Insofar as the original intention is to intervene in certain kinds of reductive anarcho-primitivism, like Zerzan and Co., I know he’s arguing with, and he said as much. I’d say that’s a valid project politically and anthropologically.

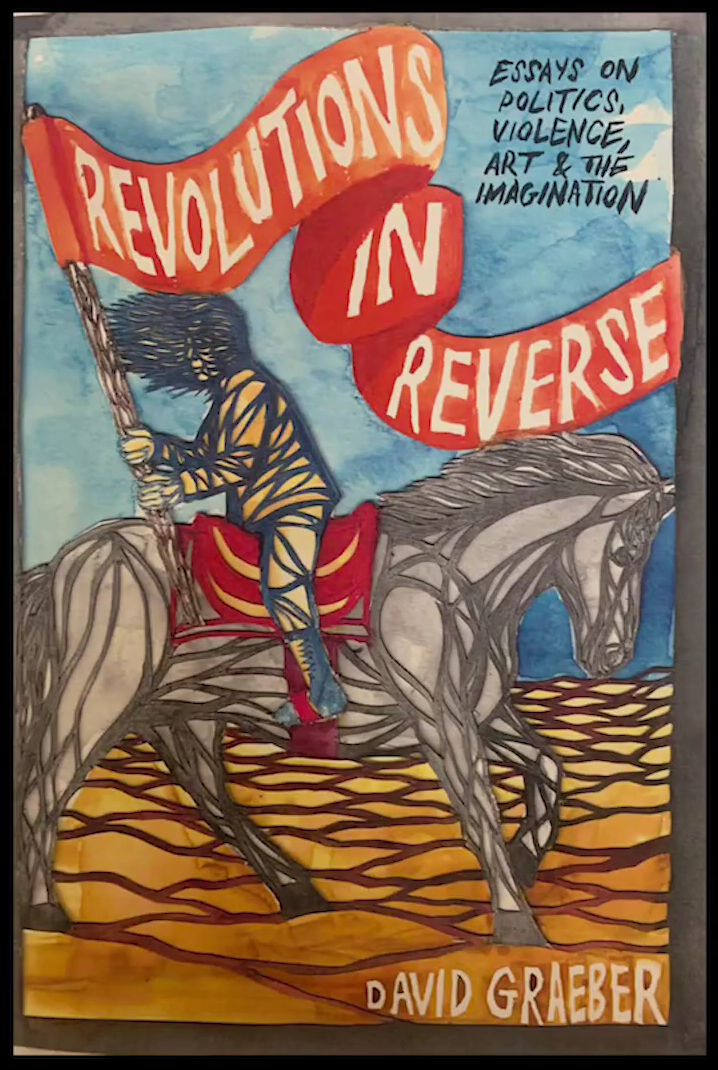

But in the end, does the book itself constitute a better materialist analysis all the time than some of that stuff? Maybe not always. And maybe we could blame Wengrow, or blame the review process and all that. But maybe that’s also a bit of a cop-out. If the book is idealistic, it is also partly because of how David liked to work with the idea of the imagination and its power, for better or for worse, right? Which we can see, for example, in the essay, “Revolution in Reverse” which originally published by RAG!:

Chris: It was in the very first issue of the Radical Anthropology. And then he published sorts of other places, which I suppose is allowed.

Erica: That’s it, it was published by RAG and then later by Autonomedia. And in fact, I brought the book, I brought like a whole bunch of a stack of these books today, actually kindly advanced to me by Jim at Autonamedia. Thank you, Jim, if you’re there. And it’s super fortuitous. I love it because check it out. The essay, I think it’s so funny that this is the essay that you guys published. It starts, “all power to the imagination”. The first line there.

Chris: It was a slogan in the ’68 rebellion.

Erica: Yeah, I mean, I know, and he’s put it in quotes.

Erica: “Anyone involved in radical politics has heard these expressions 1000 times.” So he knows he’s putting it in quotes.

Chris: “You’re not just your television. There is a fault in reality.”

Erica: And then on the following page, there’s this. Okay, I just thought I’d point us to this briefly.

Right and Left political perspectives are founded, above all, on different assumptions about the ultimate realities of power. The Right is rooted in a political ontology of violence, where being realistic means taking into account the forces of destruction. In reply the Left has consistently proposed variations on a political ontology of the imagination, in which the forces that are seen as the ultimate realities that need to be taken into account are those forces (of production, creativity...) that bring things into being.[2]

And you know, there’s so much about This is just one example. There’s a lot of places where David writes about the imagination itself. There’s, oh, I meant to say there’s a piece that just came out in an Italian special issue done by Irene that Simona is in the Zoom room. Plug Irene’s piece now. And also, there’s the Malinowski lecture. I don’t even remember what it’s called, but the Malinowski lecture. It’s got the words imagination in the title. Right before the lecture, I thought, oh, I’d squeezed that in, but I didn’t get it here. But I always-- it’s the one that’s got the analysis of crime TV. And I always remember it. When I do my property and propriety lecture, I always put up this taboo diagram that I made with Microsoft Word that I feel very proud of. And I call myself a small god of Microsoft Word every time I show this. I’m so proud of being able to do this thing. And it’s because every time I do it, I remember David preparing his Lecture, trying to get these two arrows to stop going like this, Microsoft Word, so that they can make a perfect triangle, and it was like, and no, and it’s just it struck in my mouth forever. Occultist, yeah, I know, but yeah, more triangles, more triangles, no, it’s great, it’s about anyway. Check the Malinowski lecture, check this essay, check, you know, the various secondary sources that are now talking about.

Chris: A pessimistic response to the feeling that the revolution is going in reverse, of course. I mean, it’s post-Seattle. I mean, Seattle reverse for David.

Erica: Oh, it’s so hard. It’s so hard to read both. David, my own dissertation, like some of the, just written, my dissertation is written as a critique of. It’s written in a moment where it seems possible and politically useful to critique anarchist social movements from within as if we have a vibrant social movement that is capable of managing self-critique and improving and like it’s just written at a certain moment where there’s like a lot of optimism where and now when I look at it, it’s very hard to read this stuff. Very hard.

Chris: It’s emotionally difficult.

Erica: Yeah, it’s very sad. The political... but you know. It’s really hard to read stuff for a lot of reasons. But anyway, does this material, for example, on the imagination in this essay and elsewhere, which is really interesting, David does really great work with good imagination.

Chris: As we haven’t got all that much time, are you going to say anything about the main question asked in the Dawn of Everything? How did we get stuck?

Erica: I’m gonna continue... No, I mean, no, I’m not gonna do that. No, I’m not actually gonna do that.

Chris: Oh, I see.

Erica: I could do that when I finish what I’ve got prepared here, actually. Like, I don’t mind if you, you know, if there’s time, I don’t mind, we can get to that. I don’t mind addressing that, but I’m not gonna cut myself off.

Chris: That’s fine.

Erica: I’m just gonna finish. So, because I wanted to make sure to get in, does this, the point is, does this, the material, theorizing the imagination that I pointed to and everything, does it justify every, I mean, in a way I’m addressing what you’re asking, does this justify everything in the dawn of everything? Am I trying to justify the... approach to history and freedom and everything taken in the dawn of everything by pointing to what I think is some pretty good stuff on imagination? No, but I do think it provides a vantage point and a generous one, a useful one, on why the dawn might be a little overdrawn in the idealism category.

So my best apologia for the optimism and idealism and the privileging of freedom, okay, in ‘The Dawn’, would possibly be to point people to this and other essays David wrote about the imagination, and also point people to the playful manifesto about play, which you can’t find easily yet, but maybe you will soon, which I mentioned before.

I can skip through some of this, but not much. I want to just make sure I get the summary points in, which is what? Yes, my inner historical materialist is unsatisfied in certain aspects of the book, okay? But also, as I said before, I don’t want this statement to be taken to mean that I’m somehow against David’s anthropology in general. The collection of David’s work is large, it’s heterogeneous. It’s dialogical. It’s emerging in conversations. David wrote about this A lot. As I said, a lot of his articles are conversations with a particular person. So all the books are different. ‘The Dawn’ is the Wengrow book. And it wasn’t supposed to be the be-all and the end-all, you know, the capstone of his career. He just very sadly happened to die right before that one came out, with those who survived him, making as big of a show of it as possible. But for David, for example, the pirate book was like... more interesting, maybe, and we don’t even have it. We do have the Pirate Enlightenment book, but that text is just the chapter on pirates that was cut from the Salon’s book because the King’s book got really long. And that chapter was really long, like very indulgently long, precisely because it was the seed essay for a book. The book was supposed to be filled out in all sorts of ways. And in the end, that book didn’t happen and we don’t have the whole thing. We just have the long essay that was supposed to be a short chapter, but it’s the fact it’s so long that it looks like what the book was supposed to be. But you know, so there was the pirate’s book, there was the sacrifice book, there were supposed to be many other books, okay, above and beyond the Wengrow book. The value book is great. Now, the fragments of an anarchist anthropology is great, obviously.

I just want to remember the good times. And I think I’m fussing here because I’m like, How am I going to end this thing?

I want to explain that I kind of, like, the reason I arranged to, it’s a little late, it’s a little wonky as usual, but the reason that I planned the thing today, like, I’m going to do my lecture, and then we’re going to have a debate, and then I’m going to talk, and then we’re going to leave, is because I just, I wanted to explain that I’m not really that into, like, taking questions, related to David right now. And I know that’s what would happen if like we had an old discussion period at the end of this talk, like we’d end up talking about it. And like I’m happy to share what I’ve shared. I really am. And I’m super happy for the invitation. But if anyone wants more of the backstory, you know, the ethnography related to David himself and all this, it’s just some really important stuff needs to happen first.

I don’t want to be asked any more questions about the famous ex. Well, I am having trouble publishing my own very excellent work. So this is why I’m ending today with a public service announcement, okay? This is why I really wanted to make sure I get in...

Then you can drill me about the macaw. Everything I didn’t say.

Chris: Unless you were joking about saying anything whatsoever about one macaw or any other macaw.

Erica: The macaw is a placeholder. For all that is.

Okay, so the point is, where’s Mark? We also had a conversation. You’ll appreciate this, because we had a, not just pick you up, but we had a conversation a couple weeks ago where this sort of stuff came up a little bit, so you’ll feel like seen a little bit here.

Public Service Announcement

Erica: So, the point is that

And to be honest, it was kind of annoying to have to explain that nobody there treats Lagley’s like they’re raw material. When me and my talent could eat them for breakfast like my milk is cereal, you know?

And this is a letter that I just don’t want to have to write again. I just really don’t want to have to write this letter again.

So let it be known around the world!

That if I’m not already known as “...Graeber’s girl...”

...it’s because that’s how I arranged it!

As David got famous and lived his life on Twitter,

I kept our social media lives apart, succeeding for a decade.

Meanwhile, I published as June Thunderstorm in The Baffler.

And it never came out, not even in Best American Essays.

So, Livelies, a.k.a. a cult feature of anarchism number one, personified,

needs no rescuing from invisibility

by bourgeois subjects, the kind to treat

my current professional obscurity

as their own convenient economic opportunity.

But that anyone interested in the Graeber biography

will feel free to offer me an appropriate contract in advance.

Well, in my respect for my highly gendered, highly ethnographic authority.

Would they like it in the format of a dialogical interview?

Or perhaps they prefer my prose with style of peer review?

A folio of crystallarias collaged by Lagulitha’s Benjamin.

Theoretical exegesis or vinettes from behind the scenes.

‘Cause transcendent or eminent, Latvia or gory,

I think I’m gonna take Barbara Ehreich’s advice and write our own story.

I mean, come on. As if that is something, I would let another bro sell.

I don’t throw it on like Barksdale when I could play Stringer Balk.

One, Two, Three, Four, Five!

O, okay, who’s laughing?

Who made it out alive?

And who’s hitting a wall

in the hallowed halls

between thunderstorms

mimetic archive?

Which reminds me,

just one more thing.

Are we having our video? Yeah. Dramatic pause. This is the caveat. Coming through and all.

There’s one more thing. Just one thing that bothers me. So anytime we all want to hear the story of the clever anthropologist. It’s like an archaeologist with red smoke people that are still alive. See, I know this because, see, I heard of the guy, very, very smart guy, important guy. To what? Because all these books are done. Let me read some of the past one myself. Think one. Thought or something. Very interesting stuff. So I can understand why... My goodness, I’m sorry. Oh, just... Let me, just wipe that, wipe that, wipe that up. Lieutenant Colombo, I’m sorry. I really must protest. You’ve been harassing me and my wife in our own home for over a week now, and I really must ask you to get to the point. I’m sorry, sir. I’m sorry. Listen, I don’t want to take your time and... I’ll just get straight to the point. Here’s my question. We all want to hear the story of the clever row and apology. Sorry. That’s clear. But now, why? Why would the ex-girlfriend want to write the book about that ex-boyfriend had the power? Like, yeah, she’s clearly got the material. She’s, you know, clearly the best person to do it out. I’m convinced there. But what’s the motivation? I mean, you know, because I was talking to this lady last week, you know, I’m doing a round of interviews and I had to get by and I was sitting in the row, and we were talking and, you know, she’s a very nice lady. And you know, she’s an anthropologist, too. She’s got her book herself. She’s got her own book. She’s sent it to a very fancy press four years ago or something. It’s an embroiled type canon. Duke. That was it. Duke University Press. So she’s got her own book. And she’s wanted to finish it for four years. So-- and apparently, she hasn’t been able to because I know it’s a fortunate business. So my question is, is she really going to write the book about the ex-boyfriend, which she could write her own book? And it would seem to me, from her perspectives, you know, that this guy’s already, you know, wasted a lot of her time, you know. And she cleverly seem to hate about it from her perspective. So it’s pretty good to put that in one book. Make this book first. That’s my question. It’s a question of motivation. This is not clear to me.[3]

You know, sometimes I think if ever I do, write something about David as a person, it might be in the genre of a Colombo episode. It wouldn’t be called a clever anthropologist. It would be called the King’s Two Bodies.

Chris: Yes.

Erica: If you know, you know. Anyway, if you’re interested to hear more about that or my work in general, please do click to subscribe. This is the moment where we put the... You know, where we try to take people’s money.

Chris: Erica, a question we’re all asking is, are you coming to the pub?

Erica: Of course I’m coming from the pub. All things end, all good things end with the pub. And I’m coming back next year. And, you know, that is the final, final, final word. There we go:

This is where we ask you for money. And say... no, actually, it’s more than that, I’m taking the piss. Yes, I’m wanting you to donate, but also the idea is I’m going to be getting off of the social media stuff, Facebook, Instagram, and all this, and I am going to be using this as my main way of keeping in touch with people, so it’s just good for you to know about.

So I wanted to plug that and just finish by saying, if you’re interested in anything you heard today, the first part, the middle part, the end part, the fabulous closing scene, then I will be back for a sequel next fall, I believe, with RAG in October to discuss my latest piece ‘On Authenticity’, which is also available online, in hard copy, and I was going to read something from it, but we don’t have time.

I think I will just say that, one more, one more little verse. I just need to make sure I get in, you know? And it says,

There’s maybe just one more thing

that’s important to wrap down

which is that

Lagulis, AKA Thunderstorm

is a master of form and content!

of prophecy and portent!