Kelly Struthers Montford and Chloë Taylor

Colonialism and Animality

Anti-Colonial Perspectives in Critical Animal Studies

Routledge Advances in Critical Diversities

Foreword: Thinking “critically” about animals after colonialism

Colonialism and animality: An introduction

Section I. Tensions and alliances between animal and decolonial activisms

1 An Indigenous critique of Critical Animal Studies

The logics of white supremacy: anthropocentrism

The colonial politics of animal recognition

Indigenous cosmologies and animality

Positions and perspectives on the seal hunt

Grounded normativity, Indigenous modernity, and the colonial politics of recognition

Beyond shallow coalitions: what might a decolonizing solidarity look like?

Animal resistance against capitalist domination

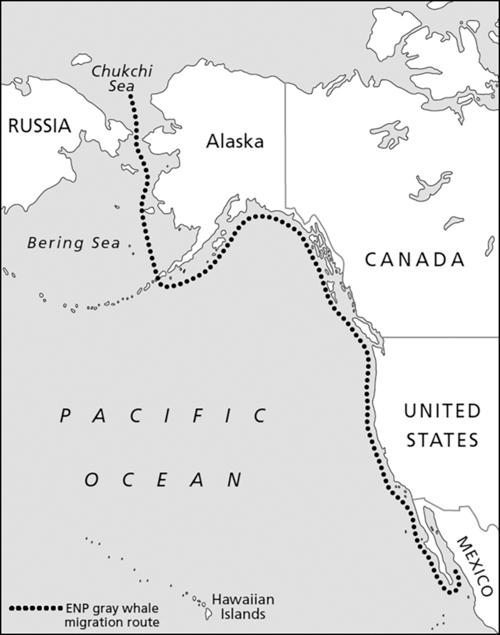

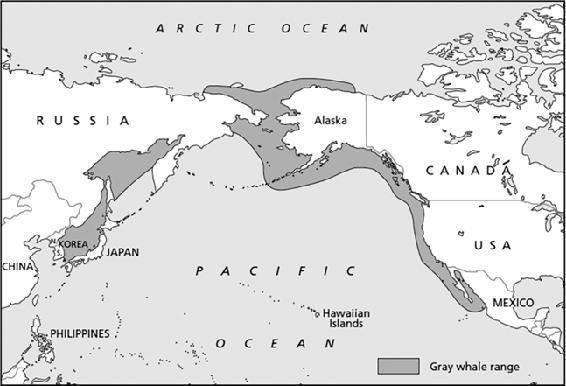

3 Makah whaling and the (non)ecological Indian

Histories: the Makah, gray whales, the International Whaling Commission

The Makah whale again: scientific and legal uncertainties

The optics of ecological and ethical harm

Mutual disavowal in the Makah whaling conflict

Section II. Revisiting the stereotypes of Indigenous peoples’ relationships with animals

4 Veganism and Mi’kmaq legends

5 Growling ontologies: Indigeneity, becoming-souls and settler colonial inaccessibility

6 Beyond edibility: Towards a nonspeciesist, decolonial food ontology

Critical ontologies and ontological veganism

The politics of dominant food ontologies in Western settler colonial societies

The politics of alternative food ontologies

Conclusions: for a contextual, relational, and ontological veganism

Section III. Cultural perspectives

7 He(a)rd: Animal cultures and anti-colonial politics

8 Dingoes and dog whistling: A cultural politics of race and species in Australia

‘According to the shooter he was “a hybrid”’

9. Haunting pigs, swimming jaguars: Mourning, animals and ayahuasca.

Section IV. Colonialism, animals, and the law

10 Constitutional protections for animals: A comparative animal-centred and postcolonial reading

Part I: Constitutional hopes and disappointments – the persistence of legal welfarism

Part II: Constitutional initiatives outside of Europe – resisting imperial representations

The Louisiana State Penitentiary: a plantation prison

The geography of the Angola Prison Rodeo

Colonial encounters in the meeting of the South and the West

Conclusions: race, animality, and the animal

12 Towards a theory of multi-species carcerality

Overview of penitentiary agriculture in Canada

Enclosure and territorialization

Front Matter

Colonialism and Animality

The fields of settler colonial, decolonial, and postcolonial studies, as well as Critical Animal Studies are growing rapidly, but how do the implications of these endeavours intersect? Colonialism and Animality: Anti-Colonial Perspectives in Critical Animal Studies explores some of the ways that the oppression of Indigenous persons and more-than-human animals are interconnected.

Composed of 12 chapters by an international team of specialists plus a Foreword by Dinesh Wadiwel, the book is divided into four themes:

-

Tensions and Alliances between Animal and Decolonial Activisms

-

Revisiting the Stereotypes of Indigenous Peoples’ Relationships with Animals

-

Cultural Perspectives

-

Colonialism, Animals, and the Law

This book will be of interest to undergraduate and postgraduate students, activists, as well as postdoctoral scholars, working in the areas of Critical Animal Studies, Native Studies, postcolonial and critical race studies, with particular chapters being of interest to scholars and students in other fields, such as Cultural Studies, Animal Law, Critical Prison Studies, and Critical Criminology.

Kelly Struthers Montford is Assistant Professor at the Department of History and Sociology at the University of British Columbia Okanagan.

Chloë Taylor is Professor of Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada.

Routledge Advances in Critical Diversities

Series Editors: Yvette Taylor and Sally Hines

5 Exploring LGBT Spaces and Communities

Eleanor Formby

6 Marginal Bodies, Trans Utopias

Caterina Nirta

7 Sexualities Research

Critical Interjections, Diverse Methodologies, and Practical Applications

Edited by Andrew King, Ana Cristina Santos and Isabel Crowhurst

8 Queer Business

Queering Organization Sexualities

Nick Rumens

9 Queer in Africa

LGBTQI Identities, Citizenship, and Activism

Edited by Zethu Matebeni, Surya Monro and Vasu Reddy

10 Gender Verification and the Making of the Female Body in Sport

A History of the Present

Sonja Erikainen

11 Colonialism and Animality

Anti-Colonial Perspectives in Critical Animal Studies

Edited by Kelly Struthers Montford and Chloë Taylor

12 Disability and Animality

Crip Perspectives in Critical Animal Studies

Edited by Stephanie Jenkins, Kelly Struthers Montford, and Chloë Taylor

For more information go to https://www.routledge.com/sociology/series/RACD

Title Page

Colonialism and Animality

Anti-Colonial Perspectives in Critical Animal Studies

Edited by

Kelly Struthers Montford

and Chloë Taylor

Publisher Details

First published 2020

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2020 selection and editorial matter, Kelly Struthers Montford and Chloë Taylor; individual chapters, the contributors

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Montford, Kelly Struthers, editor. | Taylor, Chloë, 1976– editor.

Title: Colonialism and animality : anti-colonial perspectives in critical animal studies / edited by Kelly Struthers Montford and Chloë Taylor.

Description: Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY : Routledge, 2020. |

Series: Routledge advances in critical diversities | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019054020 (print) | LCCN 2019054021 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Animal rights. | Imperialism. | Speciesism. | Human-animal relationships.

Classification: LCC HV4708 .C655 2020 (print) | LCC HV4708 (ebook) | DDC 179/.3—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019054020

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019054021

ISBN: 978-0-367-85612-0 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-003-01389-1 (ebk)

Typeset in Times New Roman

by codeMantra

Dedication

Dedicated to the memory of the animal residents of Farm Animal Rescue and Rehoming Movement (FARRM) who died in the Spring of 2019. The human and animal residents at FARRM were integral to the conference from which this volume emerges, generously opening their homes and allowing us the joy of their company.

Figures

Contributors

Billy-Ray Belcourt is a writer and academic from the Driftpile Cree Nation. He is a PhD candidate and 2018 Pierre Elliott Trudeau Foundation Scholar at the Department of English and Film Studies in the University of Alberta; his doctoral project is a creative-theoretical one called “The Conspiracy of NDN Joy.” He is also a Rhodes Scholar and holds an MSt in Women’s Studies from the University of Oxford. In the First Nations Youth category, Belcourt received a 2019 Indspire Award, which is the highest honour the Indigenous community bestows on its own leaders. Billy-Ray’s debut book of poems, This Wound Is a World (Frontenac House 2017), won the 2018 Griffin Poetry Prize (making him the youngest winner ever) and the 2018 Robert Kroetsch City of Edmonton Book Prize. It was also named the Most Significant Book of Poetry in English by an Emerging Indigenous Writer at the 2018 Indigenous Voices Awards. This Wound Is a World was a finalist for the 2018 Governor General’s Literary Award for Poetry, the 2018 Robert Kroetsch Award for Poetry, the 2018 Gerald Lampert Memorial Award, and the 2018 Raymond Souster Award, both of the latter via the Canadian League of Poets, and was named by CBC Books as the best “Canadian poetry” collection of 2017.

Darren Chang is an independent scholar who completed an MA in political philosophy and Critical Animal Studies at Queen’s University in 2017, under the supervision of Will Kymlicka. Darren’s MA research explored how farmed animal sanctuaries and animal rights/liberation activists could overcome the speciesist zoning bylaws segregating farmed animals and excluding them from urban spaces, while invisibilizing and confining them to rural agricultural zones. Darren has been participating in grassroots animal rights/liberation activism since 2011.

Lauren Corman teaches classes in the areas of Critical Animal Studies and contemporary social theory. Her intersectional research draws on feminist, anti-racist, posthumanist, post/anti-colonial, and environmental approaches to the “question of the animal.” Subsequent to her studies on slaughterhouse labour, Corman’s PhD focused on voice, politics, and the animal rights and liberation movements. Her current scholarship carries forward these threads to investigate ideas related to agency, resistance, and (interspecies) subjectivity. Her interdisciplinary work bridges the social and natural sciences through cognitive ethology, which explores non-human animal cultures and societies. Corman is interested in coalition building across social, environmental, and animal movements, and links her work to larger anti-capitalist struggles. She maintains her longstanding commitments to critical pedagogy, and also publishes in this area. She hosted and produced the animal advocacy radio show, Animal Voices, for about a decade. She is currently collaborating with filmmaker Karol Orzechowski (Maximum Tolerated Dose) on a documentary about non-human animals and intersectionality.

Maneesha Deckha is Professor and Lansdowne Chair in Law at the University of Victoria in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. Her research interests include Critical Animal Studies, critical animal law, health law and policy, postcolonial theory, and feminist theory. Her interdisciplinary scholarship dedicated to an intersectional and Critical Animal Studies analysis of law and legality has appeared in American Quarterly, Hypatia, the Journal of Critical Animal Studies, and the McGill Law Journal, among other venues, and has been supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. She has held the Fulbright Visiting Chair in Law and Society at New York University for her work on animals, culture, and legal subjectivity. She currently serves as Director of the Animals & Society Research Initiative at the University of Victoria as well as on the Editorial Boards of Politics and Animals and Hypatia.

Kathryn Gillespie is a writer, feminist geographer, and Critical Animal Studies scholar. Her research and teaching interests focus on feminist theory and methods, food and agriculture, political economy, Critical Animal Studies, critical race theory, postcolonial studies, incarceration/prison studies, gender and sexuality, and human-environment relations. She is the author of The Cow with Ear Tag #1389 (University of Chicago Press, 2018). She has also published in numerous scholarly journals and has co-edited three books: Vulnerable Witness: The Politics of Grief in the Field (University of California Press, 2018, co-edited with Patricia J. Lopez), Critical Animal Geographies: Politics, Intersections and Hierarchies in a Multispecies World (Routledge, 2015, co-edited with Rosemary-Claire Collard), and Economies of Death: Economic Logics of Killable Life and Grievable Death (Routledge, 2015, co-edited with Patricia J. Lopez). Gillespie was an Animal Studies Postdoctoral Fellow at Wesleyan University and has taught various courses at the University of Washington. She has volunteered with Freedom Education Project Puget Sound (a Puget Sound, Washington-based prison education organization), Books to Prisoners (a Seattle organization that receives and fills book requests from prisoners throughout the United States), Food Empowerment Project (a food justice organization in Cotati, CA), and Pigs Peace Sanctuary (a sanctuary for pigs in Stanwood, WA).

Alexandra Isfahani-Hammond is Associate Professor Emeritus of Comparative Literature and Luso-Brazilian Studies at the University of California, San Diego. She has written extensively on the legacies of African enslavement and Critical Animal Studies, with publications including White Negritude: Race, Writing and Brazilian Cultural Identity (Palgrave-Macmillan, 2008) and the edited collection The Masters and the Slaves: Plantation Relations and Mestizaje in American Imaginaries (Palgrave-Macmillan, 2005). Isfahani-Hammond’s current book project, “Home Sick,” blends theory with creative nonfiction to meditate on grief, end of life, the medical-industrial complex, Islamophobia, and the commodification of (human and non-human) animals. “Home Sick” is concerned with interconnected forms of caregiving, ministering to both the dying and living in attunement to the suffering of billions of animals each day, for intimate dealings with dying bodies reframe what it means to be an animal. In addition to her scholarly publications, Isfahani-Hammond has written for popular news media, with publications in The Advocate, CounterPunch, Ms. Magazine (blog), Persianesque: Iranian Magazine, and Truthout.

Claire Jean Kim is Professor of Political Science and Asian American Studies at University of California, Irvine, where she teaches classes on comparative race studies and human-animal studies. She received her BA in Government from Harvard College and her PhD in Political Science from Yale University. Her first book, Bitter Fruit: The Politics of Black-Korean Conflict in New York City (Yale University Press 2000), won two awards from the American Political Science Association: the Ralph Bunche Award for the Best Book on Ethnic and Cultural Pluralism and the Best Book Award from the Organized Section on Race and Ethnicity. Her second book, Dangerous Crossings: Race, Species, and Nature in a Multicultural Age (Cambridge University Press 2015), received the Best Book Award from the APSA’s Organized Section on Race and Ethnicity as well. Dr Kim has also written numerous journal articles, book chapters, and essays. She was co-guest editor of a special issue of American Quarterly, “Species/Race/Sex” (September 2013), and co-organizer of the Race and Animals Institute at Wesleyan University in 2016. She is a past recipient of a grant from the University of California Center for New Racial Studies, and she has been a fellow at the University of California Humanities Research Institute and a visiting fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, NJ. She is currently working on a book entitled Asian Americans in an Anti-Black World.

Fiona Probyn-Rapsey is a Professor of Humanities and Social Inquiry at the University of Wollongong, Australia. Previously, Fiona was Associate Professor at the Department of Gender and Cultural Studies in the University of Sydney from 2003 to 2016. Fiona’s research connects feminist critical race studies and animal studies (also known as human-animal studies), examining where, when, and how gender, race, and species intersect. Her first book, Made to Matter: White Fathers, Stolen Generations (2013), examines how the white fathers of Indigenous children (many now part of the Stolen Generations) reacted to and were positioned by Australian assimilation policies. This book highlights a research interest in the reproductive and biopolitical nature of settler colonial societies, a common thread that extends into more recent research in animal studies, including three co-edited books, Animal Death (2013), Animals in the Anthropocene: Critical Perspectives on Non-Human Futures (2015), and Animaladies (2018). From 2011 to 2015, Fiona was convenor (and founder) of HARN: Human Animal Research Network at the University of Sydney. Fiona is currently working on a monograph on the cultural politics of eradication.

Margaret Robinson is a feminist scholar from Eskikewa’kik, Nova Scotia, and a member of the Lennox Island First Nation. She is currently Assistant Professor in the Departments of English and of Sociology and Social Anthropology at Dalhousie University, and an Affiliate Scientist at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto.

Kelly Struthers Montford is Assistant Professor at the Department of History and Sociology in the University of British Columbia Okanagan. Previously, she was a postdoctoral research fellow in punishment, law, and social theory at the Centre for Criminology and Sociolegal Studies in the University of Toronto. She received her PhD in sociology from the University of Alberta in 2017. Her research bridges settler colonial studies, punishment and captivity, animal studies, and law, and has been published in Radical Philosophy Review, the New Criminal Law Review, PhiloSophia, the Canadian Journal of Women and the Law, Societies, and PhaenEx: Journal of Existentialist and Phenomenological Theory and Culture, among other venues.

Chloë Taylor is Professor of Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada. She has a PhD in Philosophy from the University of Toronto and was a postdoctoral fellow at the Department of Philosophy in McGill University. Her research interests include 20th-century French philosophy, philosophy of gender and sexuality, Critical Animal Studies, food politics, and Anthropocene Studies. She is the author of Foucault, Guidebook to Foucault’s the History of Sexuality (Routledge 2016) and The Culture of Confession from Augustine to Foucault (Routledge 2008), and the co-editor of Feminist Philosophies of Life (McGill-Queens University Press 2016) and Asian Perspectives on Animal Ethics (Routledge 2014). She has also published peer-reviewed articles in journals such as Hypatia, Feminist Studies, Philosophy Today, Ancient Philosophy, Postmodern Culture, Foucault Studies, Social Philosophy Today, and the Journal for Critical Animal Studies.

Dinesh Wadiwel is a senior lecturer in human rights and socio-legal studies, with a background in social and political theory. He has had over 15 years of experience working within civil society organizations, including in anti-poverty and disability rights roles. Dinesh’s current book project explores the relationship between animals and capitalism. This builds on his monograph, The War against Animals (Brill, 2015). Dinesh is also the co-editor of Foucault and Animals (Brill, 2016) and Animals in the Anthropocene (University of Sydney Press, 2015). He is also involved in a project exploring the application of the United Nations Convention against Torture to the treatment of people with disability.

Vanessa Watts is Mohawk and Anishinaabe Bear Clan from Six Nations of the Grand River. She is Academic Director of Indigenous Studies at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. Vanessa’s research focuses on Indigenous material knowledge production sites among the Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe. She examines the roles of gender, sexuality, spirit, and other-than-humans in how material knowledge is produced and inherited within Indigenous communities amidst colonialism. Her research is framed within broader discussions of how epistemology and ontology are oriented to Indigenous cosmologies. Vanessa also holds an Arts Research Board grant entitled, “Working Colonial Sexualities: Indigenous Sex Workers and the Colonial Desire,” which will interrogate feminist approaches to agency in the sex trade industry in an effort to make space for the voices of Indigenous sex workers. This research will document how power and agency are particularly inaccessible to Indigenous women in the sex trade as well as contextualize discussions of prostitution, colonization, and Indigenous women in Canada’s efforts towards decriminalization of sex work, and the discourse of empowerment embedded within it.

Foreword: Thinking “critically” about animals after colonialism

Dinesh Joseph Wadiwel

In the colonial context the settler only ends his work of breaking in the native when the latter admits loudly and intelligibly the supremacy of the white man’s values. In the period of decolonization, the colonized masses mock at these very values, insult them, and vomit them up.[1]

Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth.

As this volume attests, the colonial project—encompassing diverse rationalities of elimination, exploitation, and assimilation[2]—cannot be easily disentangled from our prevailing relationships with animals. In part, this reflects the material reality that colonialism was also accompanied by the radical remaking of non-human animals and “nature.” For example, the relation between European expansion, invasion, settlement, and domination, and the development of large-scale industrial animal agriculture represents what David Nibert describes as an “entangled violence.”[3] Thus, Billy-Ray Belcourt notes (see this volume) that the context for understanding “speciesism” today includes:

the historic and ongoing elimination of Indigenous peoples and the theft of Indigenous lands for settler-colonial expansion, including animal agriculture. For that reason, we cannot address animal oppression and liberation without beginning from an understanding that settler colonialism and white supremacy are the bedrock of much of the structural violence that unfolds on occupied Indigenous territory.

Colonialism also participated in the conversion of almost all non-human life into objects for capitalist accumulation, transforming pre-existing human animal relations, and altering food production and consumption. Early forms of globalized capitalism, founded on developing supply lines of raw materials and labour between Europe and the colonies, established the beginnings of a global transformation in food production; as Eric Holt-Giménez notes this “colonial food regime was the first hegemonic regime…and had consolidated a powerful set of institutions and rules that influenced food production, processing and distribution on a world scale.”[4] Relevant to thinking about animals, this transformation of the world has intimately shaped the diets of populations globally, so that the “promotion of meat production and consumption accompanied Western political, economic, and cultural influences.”[5] Finally, the colonial project came armed with a strong set of epistemic effects which produced overt resonances between processes of racialization and the construction of the non-human animal: in this respect, it is not accidental that Achille Mbembe observes that “discourse on Africa is almost always deployed in the framework (or in the fringes) of a meta-text about the animal.”[6] The distinctive form of racialization that accompanied colonialism was one that placed humans and animals within the imaginary of the “chain of being”;[7] Syl Ko offers the succinct summary that “what condemns us to our inferior status, even before we speak or act, is not merely our racial category but that our racial category is marked the most by animality.”[8] Thus, it would appear that, and despite very different histories, the challenge of thinking “critically” about animals has to grapple with the very real material transformations, violences, and erasures of colonialism, all of which paved the way for what we “know” about animals today.

All of this beckons us to think about animals in truly “critical” ways, which requires a simultaneous project of disarming colonial logics. But this is not straightforward by any means. First, how did “Critical Animal Studies” arise as a tendency, and to what extent was it complicit in the colonial project? Various histories have understood CAS as an intervention into animal studies or human/animal studies,[9] or suggested that CAS was developed “some forty years ago as a specialization within analytic philosophy.”[10] This reading of CAS appears to locate its origins within pro-animal liberation movements in industrial societies, predominantly located in the Global North. But such a perspective relies on imagining that “critical” perspectives or studies of animals have their location within venerated institutions, discourses, and debates—e.g. animal ethics after Peter Singer’s Animal Liberation, the emergence of a critique against mainstream human/animal studies in contemporary universities, the rise of vegan movements in the Global North, etc.—and forgets that diverse cultures and traditions have thought about animals in “critical” ways for a very long time; and that these ethics, practices, and ontologies continue to offer a profound critique of colonial ways of seeing, knowing, and relating to animals. The point here isn’t to pretend that CAS as an institutional formation did not have the historical location, or string of intellectual forebears that its proponents claim for it; rather, the aim is to push us to ask the more fundamental, and interesting, question: what does it mean to think critically about animals?

Secondly, in identifying these boundaries, we might then ask: which anti-colonial perspectives should be included within the boundaries of CAS? Which discourses are nominated to challenge colonial master narratives? And who initiates these projects of decolonization? For example, the conviction that veganism functions as a “moral baseline”[11] for CAS, while serving a function in aligning personal practices with scholarly commitments, also governs the borders of who we might imagine as being a committed CAS scholar. Certainly, it would appear odd that ethical vegetarians who belong to non-Judeo-Christian faith traditions such as Jainism, Hinduism, and Buddhism, which are informed by hundreds if not thousands of years of careful ethical thought and practice relating to animals, should be regarded as have nothing to offer CAS because they do not obey an imperative towards veganism. What are the rules of inclusion in CAS, and who gets to decide?

Thirdly, we might ask epistemically, to what extent does CAS participate in seeing and knowing animals in ways that reflect settler rationalities? Is it even possible to think about animals “critically” outside of the tools we have inherited from colonialism? After all, we are reminded again and again that the colonial project did not just seek to materially remake the world through social, economic, and political violence, but simultaneously wrought an epistemic violence that shaped how we saw the world; and impressed upon us values that shaped how we saw ourselves. As Edward Said pointed out, the colonial enterprise required the establishment of the object of imperialist knowledge as a site of both domination and truth: “to have such knowledge of such a thing is to dominate it, to have authority over it.”[12] This makes it difficult to even think about decolonization without simultaneously evoking the language of the colonists—since their perspective continues, almost everywhere, to dominate with apparent universality as the only world that appears rational and comprehensible. As discussed above, animals too were framed as part of this remaking of the world. We thus face an extraordinary challenge to think “critically” about animals, while simultaneously holding in check and resisting colonial logics. For example, as Claire Jean Kim describes in an analysis of contention over Makah whale hunting (see this volume), some animal advocates openly reproduce settler logics which trivializing “concerns about tribal or racial justice.” Resistance to colonial violence here depends upon being able to produce an alternative set of realities without simply, by default, reinscribing the master’s discourse.

Finally, in reproducing alternative knowledges about animals, how do we avoid simply cataloguing diverse and irreconcilable perspectives which do not in themselves lead to change? How do we engage in decolonization work that actually leads to the transformation of societies, and heads towards a break in the cycle of colonial violence and the elimination of violence towards animals? As Fayaz Chagani notes: “The normative horizon for postcolonial thinking—its reason for critiquing humanism in the first place—has been a world in which non-coercive relationships between cultures and societies are possible.”[13] What does this project look like? And who gets to decide?

The above challenges might be read as invitation to inaction. However, inaction is not a possibility. This is because of the political urgency of the colonial violence we are responding to; this violence is not insignificant, at least to those who experience it. We need to respond; the question is how. In other words, the problem before us is strategic in nature. If we must act, how do we act? What approach do we take? What are the effects we are seeking to induce?

Reflecting on the project of teaching towards transformation, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak offers I think a useful way to explore our strategy with respect to the recognition and production of anti-colonial perspectives. In this context, Spivak is particularly concerned about a tendency of teaching spaces to resist change by peddling a kind of “pluralism” which responds to the colonial narrative by simply offering alternative discourses, without necessarily engaging in change: Spivak remarks that “Most of us are not interested in changing our social relations, and pluralism is the best we can do.”[14] Against this tendency, Spivak suggests a strategy of building a collective process of change, starting with an acknowledgment of the limits of one’s own capacities and understanding:

Once we have established the story of the straight, white, Judeo-Christian, heterosexual man of property as the ethical universal, we must not replicate the same trajectory. We have limits; we cannot even learn many languages. This idea of a global fun-fair is a lousy teaching idea. One of the first things to do is to think through the limits of one’s power. One must ruthlessly undermine the story of the ethical universal, the hero. But the alternative is not constantly to evoke multiplicity; the alternative is to know and to teach the student the awareness that this is a limited sample because of one’s own inclinations and capacities to learn enough to take a larger sample. And this kind of work should be a collective enterprise. Other people will do some other work. This is how I think one should proceed, rather than make each student into a ground of multiplicity. That leads to pluralism. I ask the U.S. student: “What do you think is the inscription that allows you to think the world without any preparation? What sort of coding has produced this subject?” I think it’s hard for students to know this, but we have a responsibility to make this lesson palliative rather than destructive.[15]

I believe Spivak offers us here some useful cautions for the work of decolonization. We must “ruthlessly” take away the universalizing foundation that apparently structures what we see and take for granted. But we simultaneously must know the limits of our own knowledge and invite others to be part of the collective enterprise of making sense of a world outside of “the straight, white, Judeo-Christian, heterosexual man of property as the ethical universal.” Importantly, Spivak always reminds us of the importance of knowledge as strategy:[16] the classroom aims to use knowledge strategically to disrupt the students’ own self-certainty. Knowledge here does not proclaim to be universal; instead, it only reminds the student that the master’s discourse cannot make a claim to universality in the way that was previously taken for granted.

The present volume arose out of a very successful conference held in June of 2016, “Decolonizing Critical Animal Studies, Cripping Critical Animal Studies.” The conference in itself was an overdue offering within the circuit of animal studies conferences that had been occurring over the last decade, many of which had scarcely or not adequately addressed issues relating to race and legacies of colonialism. The 2016 conference provided some highly powerful provocations to the field, some of which I suspect challenged the self-certainty of many involved, including myself. As such this volume is timely. However, this volume was never intended as a complete or final statement on anti-colonial perspectives in CAS, nor should it be regarded as such. Instead, in line with Spivak’s commentary above, this volume might be understood as offering a strategic intervention that might provoke us to think critically about Critical Animal Studies; perhaps, as such, to actually think “critically” about animals. First, the volume provides us some insight into the functioning of the “straight, white, Judeo-Christian, heterosexual man of property as the ethical universal” within the field of animal studies, whether this is in the form of resistive ontologies, such as those discussed by Vanessa Watts, or legal analysis that challenges the presumed authority of the Global North in driving improvements in animal welfare and rights (see Maneesha Deckha). Secondly, the volume shows us the way that colonial violence towards humans interconnects with violence towards animals through colonial logics, shaping policies of annihilation (see Fiona Probyn Rapsey) and incarceration (see Kelly Struthers Montford). Finally, and importantly, this volume provides an opening to a continuing conversation on strategies of decolonization and their relationship to social movements that organize around animals. In part, these openings are relevant for the material alliances that will be required to effect decolonialization: “this kind of work should be a collective enterprise.” This will require a careful assessment of how the political terrain of existing contestation is constructed, and care in thinking about strategy and alliances (see for example Darren Chang).

By necessity such a politics requires an evolving commitment to self-determination in guiding futures and actions. The opposite of coercion—that wrought by material or symbolic violence—is the freedom to collectively determine one’s own pathway and conditions of flourishing. It is on the latter point that Margret Robinson (this volume) offers a remarkable vision for a future of flourishing, tying Indigenous sovereignty with plant-based diets and ethics:

At stake in the creation of an Indigenous veganism is the authority of Aboriginal people, especially women, to determine cultural authenticity for ourselves. Dominant white discourse portrays our cultures as embedded in the pre-colonial past. This perspective must be replaced with the recognition that Aboriginal cultures are living traditions, responsive to changing social and environmental circumstances.

This sort of vision helps me make sense of Spivak’s desire for the decolonial lesson to be “palliative rather than destructive.” Robinson here announces the demise of settler project, while simultaneously declaring a different vision for flourishing, one which might connect together Indigenous self-determination and animal flourishing. The place of veganism here is important in so far as Robinson explicitly does not embrace imperatives to plant-based diets driven by white vegan cultures, but instead unsettles the master narrative by asking how veganism might reaffirm self-determination, and with this offer a vision for non-human flourishing. Here, decolonization is necessarily a collective enterprise—one driven and articulated by those who experience the violence of colonialism. With reference to Māori communities and the development of plant-based ethics and lifestyles, Kirsty Dunn has recently observed:

It is vital, though, in this context, that any kōrero regarding veganism, plantbased kai or ‘kaimangatanga’ and any challenges or conflicts that arise with regards to customary and contemporary practices involving nonhuman animals, must be conducted by and within Māori communities. Otherwise, the imposition of a vegan ethics without the knowledge, understanding, or respect Māori experiences, narratives, concepts, and knowledges, can only repeat the role of yet another colonial project.[17]

I don’t at all intend to privilege veganism as a practice or strategy in this discussion: the strategies deployed by communities resisting legacies of, and continuing realities of, colonialism must be determined by those communities themselves within the context of a real political terrain. However, I want to highlight the way that any number of pro-animal strategies, created by those who resist colonial power, might disorient the master narratives of settler logics and provide a mechanism “by which collective power and community may be built.”[18] In this sense, many who resist colonialism are also actively resisting industrial animal agriculture;[19] the lesson for animal studies, including by necessity those who want to build a “critical” voice, is to pay attention: to know the limits of our power; understand the specifics of our history and its relation with others; avoid believing we are the movement or can control who comprises the collective project; and remain alive to those outside of our experience can teach us about the non-universality of “the story of the straight, white, Judeo-Christian, heterosexual man of property.”

This collection overall has prompted me to think again about what it means to affect a “critical” perspective on animals. What does it mean to actually be critical in our viewpoint; that is to look at the world in ways that do not simply reproduce the logics of domination that we have been forced upon us? And what does this mean for “critical” animal studies? I hope this volume helps to move these considerations forward.

I would add that there are Indigenous veganisms too, and that kaimangatanga is but one iteration of these, with its own variations or branches. Some might even choose to refrain from using the ‘vegan’ label entirely: this is my reason for refraining from presenting ‘veganism’ and ‘kaimangatanga’ as simple equivalents. Whilst some may see the word, ‘kaimangatanga’, for example, as a translation of the word ‘veganism’ or ‘vegetarianism’, others, including myself, assert that kaimangatanga stands on its own as a decolonial food ethic. Whilst there will indeed be similarities between veganism and kaimangatanga, it is my view that the latter term can accommodate a more nuanced approach towards kai-related practices and the creation and preservation of taonga, and one that can adapt and change where needed. That some of us may choose to name this way of being and relating to the world in our own language makes it, for me, a powerfully decolonial act: an act of tino rangatiratanga. This also helps us to kōrero with others in our own whānau, hapū, iwi, and in our own homes, communities, and wharekai, and to continue forging our own responses to the exploitation of animals and the environment, and the ramifications of intensive animal agriculture in Aotearoa and beyond.

(56–7)

To adopt a form of veganism – a plant-based lifestyle and ethics – that acknowledges, is based upon, and celebrates Te Ao Māori, is a break from the dominant and from the status quo and but also an act of decolonialism. It is a way to reclaim sovereignty and exercise individual choice. And finally, it is a means by which collective power and community may be built; this is evident in the existence of online forums and comment threads on Māori-based vegan and plant-based social media accounts.

The resurgence of Indigenous movements is predicated not only on the recognition of Indigenous self-determination. At a more fundamental level, it calls for the restoration of the relationship between human beings and the lifeworld, for a profound recognition of our deep interconnectedness across all species and for the recognition of the sacred in all things. Resilience, on this account, is the stand by Indigenous peoples who put their bodies on the line to protect the rights of nature. Resilience is the re-enacting of deep sacred connection. Looking towards an uncertain and increasingly problematic future, it is perhaps our best hope for survival.

(76)

Acknowledgements

This volume emerged from a conference that the co-editors organized in June of 2016, “Decolonizing Critical Animal Studies, Cripping Critical Animal Studies.” A pendant volume in Critical Animal Studies, including some of the proceedings from the conference with crip theory and critical disability studies themes, will be published separately. We would like to thank all of the participants, student helpers, and audience members who made this conference such an overwhelming success. We would also like to express our gratitude to the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the Faculty of Arts at the University of Alberta, the Kule Institute for Advanced Studies at the University of Alberta, and the Department of Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of Alberta, whose financial support made the conference possible. Billy-Ray Belcourt’s contribution to this volume is an expanded and revised version of an article that was originally published in Societies. Margaret Robinson’s chapter was originally published in the Canadian Journal of Native Studies. Fiona Probyn-Rapsey’s chapter was first published in the Animal Studies Journal. Kathryn Gillespie’s chapter is reprinted from Antipode. We thank each of these journals for permission to reproduce these articles.

We would also like to thank Dr Eloy LaBrada for their careful reading and feedback on the entirety of this text. Tessa Wotherspoon also provided research support for which we are grateful.

Colonialism and animality: An introduction

Kelly Struthers Montford and Chloë Taylor

In 2015 the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada delivered its final reports and 94 Calls to Action. The TRC was meant to document, pay witness to, and create an official record of Canada’s use of residential schools which operated for more than 100 years and targeted multiple generations of Indigenous persons with the expressed purpose of cultural assimilation. With the goal of “civilizing” Indigenous children, residents were prohibited from speaking their native languages, were malnourished, used as experimental bodies, and experienced normalized emotional, physical, and sexual violence.[20] Many residents did not survive these schools. The TRC, amongst others, has referred to residential schooling as “cultural genocide”:

Cultural genocide is the destruction of those structures and practices that allow the group to continue as a group. States that engage in cultural genocide set out to destroy the political and social institutions of the targeted group. Land is seized, and populations are forcibly transferred and their movement is restricted. Languages are banned. Spiritual leaders are persecuted, spiritual practices are forbidden, and objects of spiritual value are confiscated and destroyed. And, most significantly to the issue at hand, families are disrupted to prevent the transmission of cultural values and identity from one generation to the next.[21]

Residential schools are but one manifestation of settler colonialism’s genocidal drive that has targeted both humans and non-human others.

Other mechanisms include the Indian Act, the 60s scoop, the disproportionate and racialized apprehension of Indigenous children by child welfare agencies, lack of clean drinking water and sanitary housing conditions on reserves, the mass imprisonment of Indigenous persons, the fur trade upon which imperial wealth was amassed and consolidated, and animal agriculture that contributed to the institution of settler lifeways and the privatization of land—all of which support the Canadian state’s singularity of rule and control of territory through the suppression of Indigenous persons and self-governance.[22] The report of the National Inquiry in Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, released in 2019,[23] also included a supplementary report devoted to a legal analysis of the concept of “genocide” wherein the Inquiry concluded that the evidence and testimony collected through its process “provide[s] serious reasons to believe that Canada’s past and current policies, omissions, and actions towards First Nations Peoples, Inuit and Métis amount to genocide, in breach of Canada’s international obligations, triggering its responsibility under international law.”[24]

Paradoxically, Canada, a state charged with genocide, is also officially in a time of reconciliation, where the federal government has committed to implementing the TRC’s Calls to Action, to providing funding to support the rebuilding of First Nations, and implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.[25] Until 2016 Canada was one of four original objectors to the declaration, along with Australia, the United States, and New Zealand—each of which have reversed their position. The TRC imagines reconciliation as the abandonment of “the paternalistic and racist foundations” that have structured settler colonialism in order to go forward with nation-to-nation relationship premised on “mutual respect.” Ultimately, the TRC positions responsibility squarely upon the Canadian state and its citizens that will require a wholesale shift in relations: “Reconciliation is not an Aboriginal problem; it is a Canadian one. Virtually all aspects of Canadian society may need to be reconsidered.”[26] Although the current volume is not restricted to the Canadian context or even to settler colonialism in North America, it is in taking seriously this responsibility to reconsider the societies in which we live that this volume is premised. Reconciliation requires accounting for the past, coming to terms with the causes of and acknowledging the harm that has occurred, and a commitment to change future behaviours and relations.[27]

In fact, Maneesha Deckha has recently argued that reconciliation cannot be accomplished through a singular focus on humans, because colonialism has attempted to remake not only intra-human relationships but targeted relationships that are intertwined and play out across territory, animals, and humans.[28] By examining Indigenous Legal Orders—which position animals as persons in the sense that they are subjects, have consciousness, have their own social and familial communities, and exist for themselves rather than as property, objects, and resources—Deckha shows that reconciliation itself will have to be an inter-species process to advance decolonial efforts. Because many Indigenous worldviews often share a focus on the interconnectedness of humans, animals, and the environment, and do not draw sharp distinctions between humans, animals, and territory, the property status of animals under our current laws will impede reconciliatory initiatives in multiple registers. As Deckha writes, “If Indigenous peoples’ subjectivities are enmeshed with animal identities, bodies, and beings, then a legal order that draws a sharp and diametrically different distinction as Canadian state laws do, arguably eclipse the personhood of Indigenous peoples themselves.”[29] Given how colonialism and other projects of white supremacy have relied on the denigrated status of the animal to justify the subjugation of non-white humans and non-humans, an inter-species and more-than-human approach to decolonization is all the more urgent.

This volume is meant as a beginning, rooted in a commitment to taking seriously human-animal relations in contexts of colonialism. The insights from the TRC are not constrained to the Canadian context, but are instructive for thinking through past and ongoing projects of empire, imperialism, and colonialism that structure how we conceptualize humanity, animality, and territory. As Billy-Ray Belcourt argues, reconciliation and decolonization are not mutually exclusive. Rather, we need to be vigilant as to how claims of engaging in reconciliation can be used to support ongoing settler projects that attach themselves to, and structure our institutions and dominant practices.[30] Importantly, tension exists between how reconciliation is viewed, with the Canadian state seemingly believing that it requires Indigenous peoples to accept the singularity of colonial rule, whereas Indigenous persons understand it as “an opportunity to affirm their sovereignty and return to the ‘partnership’ ambitions they held after Confederation.”[31] This volume supports and aims to contribute to the latter understanding of reconciliation as decolonial, in that it interrogates the taken-for-grantedness of colonial states and offers alternative ways of relating at the intersections of animality and colonialism—relations that national inquiries such as the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (1996) and the TRC have shown to be profoundly altered as a driver and consequence of colonialism.[32]

The use of animals and the institution of speciesism have been integral to colonization, with humans continuing to deploy animals to achieve colonial ends. Historians have examined how settlers in North America and Australia used animals imported from Europe in their projects of conquest.[33] Some settlers could not build enclosures fast enough to contain their farmed animals, and roaming farm animals often determined the settlers’ next town. Under English law farmed animals grazing on territory provided the legal grounds for colonists to lay property rights as this constituted “productive use.”[34]

The claim that Indigenous persons were closer to animals than to white European men also functioned to cast them without culture and as inferior persons requiring civilization, justifying colonial projects. Indigenous people in North America were, for example, compared to wolves because they purportedly lived in forests and their relations were unmediated by legal property statues. Other categories of animals, such as the domesticated dog, were used to subdue those likened to wolves. Political theorist Claire Jean Kim’s research shows that influential religious leaders advised governors to use dogs to pursue Native Americans as “they act like wolves and are to be dealt with as wolves.”[35] The use of non-consenting animals and the trope of animality in projects of white supremacy have been ubiquitous. Slave owners weaponized dogs to instil terror and to “hunt” escaped slaves, and military and police regimes continue to rely on horses and dogs to suppress crowds, protests, and individuals—often Indigenous and persons of colour who threaten colonial state order.

State service animals are used as racialized weapons and are themselves exploited and killed in the “line of duty.” Yet this is duty in the service of white supremacy to which they cannot consent. Police dogs and military animals are said to have “sacrificed” their lives to the country and may be bestowed the honorary status of police officers and military heroes. In Canada, the killing of Quanto, a police dog stabbed to death by a man fleeing arrest, not only led to the incarceration in solitary confinement of an Indigenous man, Paul Joseph Vukmanich, but catalysed the Justice for Animals in Service Act, which became law on June 23, 2015.[36] The stated purpose of this Act is to “to ensure that offenders who harm those animals or assault peace officers are held fully accountable.”[37] Under this Act, those found guilty of killing law enforcement, military, or service animals carry a mandatory minimum sentence of six months. As such the killing of animals mobilized by institutions of colonialism/Indigenous suppression is an offense under the Criminal Code of Canada, even while police officers routinely kill and sexually assault persons of colour without legal or professional repercussion, animals continued to be farmed and killed for food, animals are cut open and tortured in military medical training exercises, and animals are routinely poisoned and destroyed in medical, pharmaceutical, and cosmetics testing facilities with no consequences.

While some theorists have turned to non-Western and Indigenous cultures for examples of less or non-speciesist worldviews, the relationship between anti-colonial politics and animal activism has been fraught.[38] Single-issue animal activist campaigns have often functioned to justify racism, xenophobia, and exclusion, with, to adapt Gayatri Spivak’s phrase, white humans saving animals from brown humans. For instance, the racialized practices of eating shark fins and dog meat have been marked as cruel and backward, in contrast with dominant constructions of (equally animal-based or even more carnist) Western diets as sophisticated and humane. Indigenous rights activists and animal rights activists have clashed over the issue of hunting charismatic animals such as whales and seals, often eclipsing more widespread forms of animal, colonial, and racial oppression in Western, settler societies. Ecofeminist approaches to animal ethics have been riven over the issue of Indigenous hunting; some ecofeminists have expressed dismissive views of the spiritual significance of hunting for Indigenous people[39] or have charged Indigenous people with cultural imperialism towards the animals they hunt,[40] while others, such as Val Plumwood, Deanne Curtin, and Karen Warren, have argued for contextual rather than universalizing forms of ethical vegetarianism.[41]

While these debates over hunting have focused on cultural practices of meat-eating, ecofeminist Greta Gaard and Critical Animal Studies scholar Vasile Stǎnescu have recently offered complex studies of dairy production, dairy promotion, and milk consumption at the intersections of feminism, postcolonial theory, and posthumanism.[42] In “Toward a Feminist Postcolonial Milk Studies,” Gaard shows that milk—beginning with breastmilk—is a feminist issue, and, given the ways that environmental toxins are biomagnified in human and other animals’ breastmilk, milk is an ecofeminist issue in particular. Because female non-human animals are “milked”—which, as Gaard notes, in vernacular English means “to take for everything you can get”[43]—for human consumption, milk is also a Critical Animal Studies issue, and a feminist Critical Animal Studies issue specifically. Milk is moreover a postcolonial issue because its consumption as a “pure,” “white” beverage has long been taken as a cause of European racial superiority, with people of colour purportedly being weaker and less virile because many are lactose-intolerant. Milk is also a postcolonial issue because Indigenous people have been robbed of their lands so that white settlers could graze dairy cows; because environmental pollutants from this dairy industry have harmed Indigenous people and people of colour in exacerbated, environmentally racist ways; and because food colonialism and the exportation of Western dietary norms have resulted in exponential and ecologically disastrous increases in dairy consumption in countries such as China and India.[44] For reasons such as these, Gaard demonstrates that milk must be considered at the intersections of posthumanism, feminism, and postcolonial studies, and her article begins to explore this intersectional field.

For his part, in “‘White Power Milk’: Milk, Dietary Racism, and the ‘Alt Right’,”[45] Stǎnescu examines some of the ways that milk, like Ivory soap, has been taken as a symbol of racial purity. In particular, Stǎnescu describes recent ways in which male white supremacist members of the extreme right have taken up milk consumption and lactose-tolerance as an indicator of racial superiority and white masculinity in their social media posts. In so doing, he tracks how this phenomenon perpetuates intersecting 19th- and 20th-century histories of colonialism, xenophobia and anti-immigrant sentiments, sexism and animal oppression. Perhaps most troublingly, Stǎnescu shows that this ongoing history of gender-inflected dietary racism is not only prevalent in the social media of the extreme right, but has had uptake in mainstream media and academic scholarship through the 20th century until today.

Other decolonial and postcolonial scholars have also demonstrated the interconnections between animal oppression, imperialism, and settler colonialism, and have argued for the need to centre race in Critical Animal Studies. Legal scholar Maneesha Deckha, for instance, has highlighted the ways that imperialism is justified through animalizations of racial others and condemnations of the ways colonized others treat animals, even while imperial identities are constituted through the consumption of animal bodies.[46] Jacqueline Dalziell and Dinesh Wadiwel’s article, “Live Exports, Animal Advocacy, Race and ‘Animal Nationalism’,”[47] interrogates the success of animal advocacy in cases where such advocacy taps into pre-existing perceptions of white superiority, taking the controversy over and legislative responses to live animal transport from Australia to Indonesia as their case study. Political theorist Claire Jean Kim has provided detailed examinations of the intersection of race and species in disputes over how immigrants of colour, racialized minorities, and Native people use animals in their cultural traditions, focusing on the live animal markets in San Francisco’s Chinatown, whale hunting by Indigenous peoples, and anti-Black racism in animal advocacy campaigns against dog fighting.[48]

The chapters in Section I, “Tensions and Alliances between Animal and Decolonial Activisms,” forefront these conversations. Together, Chapters 1–3 show the need for further dialogue and solidarity between decolonial and Critical Animal Studies scholars and activists. In Chapter 1, “An Indigenous Critique of Critical Animal Studies,” Cree scholar Billy-Ray Belcourt revisits his influential article, “Animal Bodies, Colonial Subjects,” arguing that speciesism and animal oppression are made possible in settler colonial contexts through the prior and ongoing dispossession and erasure of Indigenous people from the lands on which animals are now domesticated and exploited. Belcourt critiques the ways that Critical Animal Studies typically assume and operate within the “givenness” of a settler colonial state, and suggests that Critical Animal Studies should centre an analysis of Indigeneity and call for the repatriation of Indigenous lands. In Chapter 2, “Tensions in Contemporary Indigenous and Animal Advocacy Struggles: The Commercial Seal Hunt as a Case Study,” Darren Chang argues that despite conflict between multiple groups about the Canadian commercial seal hunt, foundational attention to colonial and racial capitalist relations, themselves embedded in animal exploitation, must be meaningfully thought together and addressed if we are to have any hope of addressing systems destroying wildlife. In Chapter 3, we reproduce Claire Jean Kim’s “Makah Whaling and the (Non) Ecological Indian,” first published in her important monograph, Dangerous Crossings: Race, Species, and Nature in a Multicultural Age.[49] In this chapter, Kim analyses disputes about the Makah’s decision to resume whaling after a multi-decade hiatus. Whereas animal advocates seeking to prevent the hunt relied on ecological and ethical arguments, some members of the Makah Indian nation claimed that the hunt was fundamental to their culture, and that they were once again the target of cultural imperialism. Providing a case study on single-issue versus multi-issue advocacy, Kim argues that a politics of truly considering the validity of another group’s claims would provide the conditions to recognize and attend to each other’s needs, be that of tribal justice, non-Western ontologies of life, environmental preservation, or animal protection.

Indigenous people are both idealized as living in harmony with nature and other animals and simultaneously constructed as having static cultures entirely dependent on the killing of animals. The first view romanticizes what Claire Jean Kim calls “the ecological Indian,” failing to recognize differences between diverse Indigenous cultures, and the ways that interactions with settler colonialism have transformed these manifold cultures. The second view is encapsulated by Indigenous historian Rita Laws (Choctaw Nation), who writes ironically of “How well we know the stereotype of the rugged Plains Indian: killer of buffalo, dressed in quill-decorated buckskin, elaborately feathered headdress, and leather moccasins, living in an animal-skin teepee, master of the dog and horse, and stranger to vegetables.”[50] Like the first view, the stereotype of the Indigenous hunter also fails to recognize the diversity of Indigenous cultures and transformations in these cultures over time. For instance, as Laws demonstrates, the “buffalo-as-lifestyle phenomenon” was “a direct result of European influence,” and was “limited almost exclusively to the Apaches, flourish[ing] no more than a couple hundred years.”[51] As Native Studies scholar Nathalie Kermoal has moreover argued, the focus on the Indigenous hunter privileges men’s contributions to traditional Indigenous foodways, whereas women’s gathering activities in fact provided the mainstay of many Indigenous peoples’ diets and ensured their survival through the winter months.[52] Indeed, many Indigenous cultures were characterized primarily by plant-based diets and complexly critical attitudes towards meat-eating prior to contact with Europeans.[53] For these reasons, some Indigenous activists urge a return to a plant-based diet as a form of decolonization.[54] Significantly, similar arguments have recently been advanced by Black feminist vegans and other vegans of colour,[55] indicating a growing movement challenging the paradoxical stereotype of veganism as elite and white.

Regardless of whether Indigenous people come from traditional hunter-gatherer societies or from societies with traditionally plant-based diets, it should go without saying that is entirely possible for Indigenous people to be critical of contemporary meat-production, industrialized animal agriculture, and the killing of animals in times and contexts where such violence and death are unnecessary and environmentally unsustainable. In a series of articles, Mi’kmaq scholar Margaret Robinson has argued that although the traditional diet of the Mi’kmaq was heavily based on animal foods, given the view of human-animal relations as one of siblinghood that is evident in Mi’kmaq legends, veganism is more consistent with Mi’kmaq values than meat-eating in most contemporary contexts.[56] In Mi’kmaq legends, animals sacrificed their lives to humans who treated them respectfully, and humans took those lives due exclusively to necessity. Today, when many Indigenous people live in locations where plant-based foods are available year-round, and where animal deaths do not occur in the respectful and limited manner that characterized traditional Mi’kmaq hunting, Robinson argues that meat-eating violates core Mi’kmaq values.[57] According to Robinson, veganism is in fact a way to reject the speciesism of settler colonialism which is alien to Mi’kmaq values, and is hence a way to reclaim Indigeneity, to redefine Indigenous tradition and authenticity against settler stereotypes, and to live in greater harmony with nature. For her part, Ojibway nation (Catfish clan) author and artist Linda Fisher also challenges the view of Indigenous cultures as static, and adds that Indigenous peoples are not entirely “defined” by their heritages. In “Freeing Feathered Spirits,” Fisher provides an internal critique of the ongoing use of leather, fur, quills, and feathers in Indigenous ceremonies.[58]

The chapters in Section II, “Revisiting the Stereotypes of Indigenous Peoples’ Relationships with Animals,” contribute to these conversations and challenges. Chapter 4, “Veganism and Mi’kmaq Legends,” is a reproduction of one of Margaret Robinson articles on Indigeneity and contemporary food politics. In this chapter, Robinson provides an ecofeminist argument for an Indigenous veganism. Against the perception of veganism as white and colonial, Robinson looks to Mi’kmaq legends in which humans and animals possess a shared personhood in order to account for a veganism that is “ethically, spiritually and culturally compatible with our indigeneity.” Indeed, in the contemporary colonial context of what is called Canada, Robinson argues that “Meat, as a symbol of patriarchy shared with colonizing forces, arguably binds us with white colonial culture to a greater degree than practices such as veganism, which… is far from hegemonic.” In Chapter 5, “Growling Ontologies: Indigeneity, Becoming-Souls and Settler Colonial Inaccessibility,” Mohawk (Bear Clan, Six Nations) and Anishinaabe scholar Vanessa Watts juxtapose and interrogate Indigenous and Western post-structuralist ontologies of humans and animals. Taking up the fluid, and impossible to fix-in-time nature of Indigenous cosmologies, Watts asks what it means to be always becoming bear, human, animal, and broadly souls. Rather than being constrained within the violence of the Western human/animal dualism, Watts suggests a decolonial ethos rooted in and obligated to cosmologies of animality. Finally, Chapter 6 is a co-authored chapter by the editors of this volume, titled “Beyond Edibility: Towards a Nonspeciesist, Decolonized Food Ontology.” In this chapter, we challenge ecofeminist philosopher Val Plumwood’s influential argument that “ontological vegetarianism” is necessarily “racist” towards Indigenous peoples.[59] On the contrary, we show that ontology and contextualism need not be mutually exclusive concepts. Instead, ontology, including ontologies of life and food, is inherently political and thus contextual. By drawing on archival documents we show that in Canada and the United States, our prevailing ontologies of animals and food are deliberate colonial imports that have been integral to settler land acquisition. With this in mind, we argue for a contextual vegan food ontology that resists property relations and the cogent desubjectification of animality inherent in practices of animal agriculture.

Human exceptionalism has been integral to Western settler colonial projects. Cogent with a racialized, gendered, and speciesist hierarchy of life has been the belief that culture is unique to (typically) white men. Dualisms such as nature/culture, body/mind, female/male, and animal/human have been used to mark those labelled as closer to nature, such as racialized persons, women, and animals, as less human and therefore a-cultural non-agentic non-subjects. The cultural position of animals has also been used as a marker of civility. Reverence, respect, and spiritual communion with animals and nature were used by colonists as evidence of the savagery of Indigenous peoples—a position used to justify the settler project.[60] While the role of animals and animal symbolism to human culture has received sustained academic attention,[61] a context such as ours dominated by “violent hierarchies”[62] of life has meant that little attention has been paid to non-human life worlds and cultures.

Contributing to these conversations, Section III, “Cultural Perspectives,” provides three original chapters by feminist Critical Animal Studies scholars exploring the intersection of animals and culture. In Chapter 7, “He(a)rd: Animal Cultures and Postcolonial Politics,” Lauren Corman argues that despite the forceful criticism levied by postcolonial scholars against imperial ways of knowing, being, and relating, most approaches remain humanist and thus colonial. In a move to resist colonial humanism, Corman urges us not only to account for the impact of colonialism on Indigenous human cultures, but to ask after its effects on animal cultures. By drawing on multi-disciplinary scholarship on animal cultures and societies, Corman demonstrates the interplay between colonialism and humanity’s supposed monopoly on culture. In so doing, Corman urges us to consider our responsibilities to the more-than-human when undertaking postcolonial work. In Chapter 8, “Dingoes and Dog Whistling: A Cultural Politics of Race and Species in Australia,” Fiona Probyn-Rapsey interrogates the supposed purity of the taxonomic categorization of Australian dingoes by situating this in broader discourses of racial purity that have characterized colonial genocide and white supremacy. Coming to the fore after decades of panic is a mounting concern over the extinction of the dingo—extinction that is not framed as their elimination, but rather their “mixing” with domestic dogs. These “queer” relationships between dogs and dingoes, as Probyn-Rapsey terms them, not only point to the rich social and cultural lives of canines, but resist the assumed fixity of colonial taxonomization. Rather than dog-dingo hybridity remaining a symptomatic, but also material, locus of (human) colonial genocide, racist anxiety, and projection, Probyn-Rapsey asks us to consider the potential of thinking race and species together in a manner than resists colonial divisions of life. Finally, in Chapter 9, “Haunting Pigs, Swimming Jaguars: Mourning, Animals and Ayahuasca,” Alexandra Isfahani-Hammond moves through personal and political grief as experienced subconsciously, consciously, and in altered states of consciousness. Demonstrating the inextricably of colonial, nation-state, and globalization politics, Isfahani-Hammond presents us with visceral experiences of racialized social death, animal death, and ethical harm. While the trauma and grief of harm against animals is socially and politically marginalized, Isfahani-Hammond contends that we cannot truly escape the animal transport truck nor the slaughterhouse. Instead, we remain personally and politically haunted by the animals upon whom our worlds are premised.

Animal subjugation in colonial contexts is rendered possible and normative through imported imperial legal structures. Law (and the absence of its rule, such as in protection for farmed animals and laboratory animals) shapes and regulates animal life in domestic, agricultural, research, and entertainment contexts. It also interacts with ontology and subjectivity, with human superiority and animals as property assumed as natural accounts of beingness. As such, law infiltrates our extralegal realms to shape how and whom we eat, who shares our homes with us, who is categorized as enough like humans to have pharmaceuticals and cosmetics tested on, but who yet remain legally killable, and who can remain incarcerated for entertainment or other purposes. While Western legal structures privatize animals, territory, and relationships, many see legal change as an avenue to improve the lives of animals whose exploitation is bound up in colonial ontologies.

The chapters in Section IV, “Colonialism, Animals, and the Law,” contribute to the examinations of these themes. In Chapter 10, “Constitutional Protections for Animals: A Comparative Animal-Centred and Postcolonial Reading,” postcolonial feminist theorist and animal law scholar Maneesha Deckha examines constitutional protections in Sweden, Germany, Brazil, and India which provide a contrast to the property status of animals in Canadian and US law. While these legal challenges have culminated, to varying degrees, in findings that animals are different from objects and have personhood and dignity, these findings have largely been interpreted in anthropocentric manners and have affected little practical change for animals. By considering Western and non-Western legal contexts, Deckha resists the imperialism of Eurocentric animal advocacy which often demonizes non-Western human-animal relations as uncivilized and barbaric. Deckha then asks us to consider how “progress” in animal law can be bound up in civilizing logics, while at the same time suggesting legal strategies that do not seek to uphold colonial versions of humanity, and which might achieve more practical success in resisting their status of property. In Chapter 11, “Placing Angola: Racialization, Anthropocentrism, and Settler Colonialism at the Louisiana State Penitentiary’s Angola Rodeo,” Kathryn Gillespie mobilizes empirical research on the Angola penitentiary rodeo to consider the overlapping nexus of racial capitalism, chattel slavery, settler colonialism, mass incarceration, and speciesism. Inasmuch as Angola penitentiary now exists on a former site of plantation slavery, Gillespie demonstrates the enduring legacies of colonial and racial power that not only come together in racialized mass incarceration, but through the multiple modes of subjugation and domination inherent in the spectacle of the Angola rodeo. Ultimately Gillespie shows that the analytic of dehumanization is insufficient for addressing forms of racialized and specied injustice. Instead, a decolonial and thus de-anthropocentric approach to justice is required. Finally, in Chapter 12, “Towards a Theory of Multi-Species Carcerality,” Kelly Struthers Montford uses the case of prison-based animal agriculture in the colonial context of Canada to propose four symptoms of multi-species carcerality: enclosure, de-animalization, exploited labour, and ontological and ecological toxicity. By tracing the explicitly colonial logics structuring the institutions of the prison and the animal farm in Canada at the turn of the 20th century, Struthers Montford shows that colonial tactics of territorialization, property relationships to life, and the desubjectification of animality continue to be presented as a benevolent initiative to turn prisoners into proper citizens. The toxicity of prison-based agriculture is then not contained behind prison walls but transposes geographic boundaries to sustain settler colonial aims.

Acknowledgements

Margaret Robinson’s chapter was originally published in the Canadian Journal of Native Studies. Fiona Probyn-Rapsey’s chapter was first published in the Animal Studies Journal. Kathryn Gillespie’s chapter is reprinted from Antipode. We thank each of these journals for permission to reproduce these articles.

References

Anderson, Virginia. Creatures of Empire: How Domestic Animals Transformed Early America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Arnaquq-Baril, Aletha. Angry Inuk. National Film Board of Canada, 2016. www.nfb.ca/film/angry_inuk/.

Belcourt, Billy-Ray. “The Day of the TRC Final Report: On Being in This World without Wanting It.” Rabble.Ca, December 15, 2015. http://rabble.ca/news/2015/12/day-trc-final-report-on-being-this-world-without-wanting-it.

Brueck, Julia Feliz. Veganism in an Oppressive World: A Vegans-of-Color Community Project. Sanctuary Publishers, 2017.

Calvo, Luz, and Catriona Rueda Esquibel. Decolonize Your Diet: Plant-Based Mexican- American Recipes for Health and Healing: 9781551525921: Books – Amazon.Ca. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2015. www.amazon.ca/Decolonize-Your-Diet-Plant-Based-Mexican-American/dp/1551525925.

Canada. Justice for Animals in Service Act (Quanto’s Law) (2015). https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/annualstatutes/2015_34/page-1.html.

Canada. “Reconciliation,” April 9, 2019. www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1400782178444/1529183710887.

CBC News. “Quanto’s Law Brings Closure after Police Dog’s Death, Say Police | CBC News.” CBC, October 18, 2013. www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/quanto-s-law-brings-closure-after-police-dog-s-death-say-police-1.2125668.

Curtin, Deane. Environmental Ethics for a Postcolonial World. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2005. https://rowman.com/ISBN/9780742578487/Environmental-Ethics-for-a-Postcolonial-World.

Dalziell, Jacqueline, and Dinesh Joseph Wadiwel. “Live Exports, Animal Advocacy, Race and ‘Animal Nationalism.’” In Meat Culture, edited by Annie Potts, 73–89. Boston, MA: Brill, 2016. https://brill.com/view/book/edcoll/9789004325852/B9789004325852_005.xml.

Deckha, Maneesha. “Toward a Postcolonial, Posthumanist Feminist Theory: Centralizing Race and Culture in Feminist Work on Nonhuman Animals.” Hypatia 27, no. 3 (2012): 527–545. doi:10.1111/j.1527-2001.2012.01290.x.

———. (forthcoming). “Unsettling Anthropocentric Legal Systems: Animal Personhood, Indigenous Laws, and Reconciliation Projects.” Journal of Intercultural Studies.

Derrida, Jacques. The Beast and the Sovereign, Volume I. Translated by Geoffrey Bennington. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

Fischer, John Ryan. Cattle Colonialism: An Environmental History of the Conquest of California and Hawai’i. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

Fisher, Linda. “Freeing Feathered Spirits.” In Sister Species: Women, Animals and Social Justice, edited by Lisa Kemmerer. 110–116. St. Paul, MN: Paradigm, 2011.

Gaard, Greta. “Toward a Feminist Postcolonial Milk Studies.” American Quarterly 65, no. 3 (2013): 595–618. doi:10.1353/aq.2013.0040.

Gruen, Lori. “The Faces of Animal Oppression.” In Dancing with Iris: The Philosophy of Iris Marion Young, edited by Ann Ferguson and Mechthild Nagel, 225–237. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Harper, A. Breeze, ed. Sistah Vegan: Black Female Vegans Speak on Food, Identity, Health, and Society. New York: Lantern Books, 2010.

Johnson, April. “This Indigenous Scholar Says Veganism Is More Than a Lifestyle for White People – VICE.” VICE, March 27, 2018. www.vice.com/en_ca/article/7xd8ex/this-indigenous-scholar-says-veganism-is-more-than-a-lifestyle-for-white-people.

Kermoal, Nathalie. “Métis Women’s Environmental Knowledge and the Recognition of Métis Rights.” In Living on the Land: Indigenous Women’s Understanding of Place, edited by Nathalie Kermoal and Isabel Altamirano-Jiménez, 107–137. Edmonton: Athabasca University Press, 2016.

Kheel, Marti. “License to Kill: An Ecofeminist Critique of Hunters’ Discourse.” In Animals and Women: Feminist Theoretical Explorations, edited by Carol J. Adams and Josephine Donovan, 85–125. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1995.

Kim, Claire Jean. Dangerous Crossings: Race, Species, and Nature in a Multicultural Age. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Ko, Aph, and Syl Ko. Aphro-Ism: Essays on Pop Culture, Feminism, and Black Veganism from Two Sisters. New York: Lantern Books, 2017.

Lawrence, Bonita. “Gender, Race, and the Regulation of Native Identity in Canada and the United States: An Overview.” Hypatia 18, no. 2 (2003): 3–31.