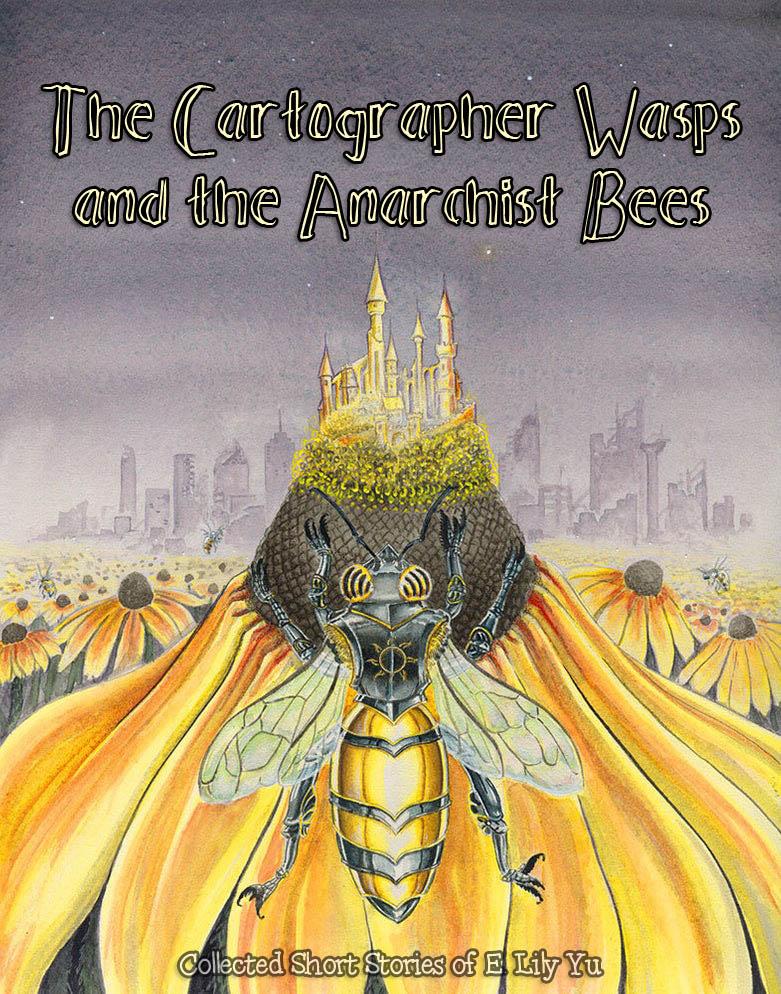

The Cartographer Wasps & The Anarchist Bees

Collected Short Stories of E. Lily Yu

The Transfiguration of María Luisa Ortega

The Cartographer Wasps and the Anarchist Bees

Local Stop on the Floating Train

Braid of Days and Wake of Nights

The Gardener and the King's Menagerie

Paul Flitch's Slap-Bang Fracas with Mister Delusio

The Witch of Orion Waste and the Boy Knight

The Wretched and the Beautiful

The White-Throated Transmigrant

The View From the Top of the Stair

The No-one Girl and the Flower of the Farther Shore

Three Variations on a Theme of Imperial Attire

The Transfiguration of María Luisa Ortega

The first time María Luisa Ortega cursed, after stabbing herself with a pair of steel tweezers, she turned into a sea urchin. Two weeks passed before a peripatetic priest found her lying in the sand and uncursed her. It was a frequent occurrence, he explained, and for this reason he always carried a squirt bottle of holy water in his bag, to bless the poor souls he found in the shapes of dolphins, fish, lobsters, or, in less fortunate cases, mollusks. “You were there only two weeks,” he said as she wrung water from her clothes. “I once found a fisherman turned into a mussel for six months, during which time his wife presumed him drowned and married another. It was only by the grace of Christ that no murder was done, for when he found them together in bed he swore the most horrible oath that had ever been heard in that town and in that instant became a starfish. His wife keeps him in a bowl of water with their wedding ring and kisses him every morning. I thought this for the best, because there is no sin in being married to both a man and a starfish. Our Lord has been gracious to you.”

“I have lost my tweezers,” she sighed, “as well as the specimens I was collecting for the university. They will think I have walked away from my job.”

“But are you not now more valuable to them than any heap of kelp could be? You know exactly how Arbacia punctulata masticates its crumbs of algae and compounds its poisons and ambulates with dreadful slowness across the tidal pool. You could write reams of papers on the details that you researched so closely these last two weeks, and perhaps they will give you a lectureship. But you must be careful not to swear.”

He smiled at her, a beautiful strong smile like the sun on the sea, and because she could not bear that smile she looked at his straw sandals and his leather bag, which was glassy and soft with use.

And María Luisa Ortega said, “No, I will not go back to the laboratory and the students dissecting their oysters, not even for a professorship. I will take holy orders, and then I shall wander the sands and collect lost souls, even as you do.”

“It is a hard and lonely life I lead,” the priest said. “I live on periwinkles and sleep on the sand, and I speak to no one but the birds and those I recover to human form.”

“I am prepared for such a life, Father,” she said.

“Then take my bag and my sandals,” he said, “and may God walk with you always.”

And smiling a beatific smile, he uttered a profanity so terrible that the seagulls dropped out of the sky.

Even as a sea lion he was handsome, with skin like silk and caramel and sweet black eyes. María Luisa kissed him on one whiskered cheek, because that was now permitted, and watched him swim into the sea, waves breaking over his golden head, until she saw him no more. Then she put on his sandals and slung his bag over her shoulder and set off across the sand.

The Cartographer Wasps and the Anarchist Bees

For longer than anyone could remember, the village of Yiwei had worn, in its orchards and under its eaves, clay-colored globes of paper that hissed and fizzed with wasps. The villagers maintained an uneasy peace with their neighbors for many years, exercising inimitable tact and circumspection. But it all ended the day a boy, digging in the riverbed, found a stone whose balance and weight pleased him. With this, he thought, he could hit a sparrow in flight. There were no sparrows to be seen, but a paper ball hung low and inviting nearby. He considered it for a moment, head cocked, then aimed and threw.

Much later, after he had been plastered and soothed, his mother scalded the fallen nest until the wasps seething in the paper were dead. In this way it was discovered that the wasp nests of Yiwei, dipped in hot water, unfurled into beautifully accurate maps of provinces near and far, inked in vegetable pigments and labeled in careful Mandarin that could be distinguished beneath a microscope.

The villagers’ subsequent incursions with bee veils and kettles of boiling water soon diminished the prosperous population to a handful. Commanded by a single stubborn foundress, the survivors folded a new nest in the shape of a paper boat, provisioned it with fallen apricots and squash blossoms, and launched themselves onto the river. Browsing cows and children fled the riverbanks as they drifted downstream, piping sea chanteys.

At last, forty miles south from where they had begun, their craft snagged on an upthrust stick and sank. Only one drowned in the evacuation, weighed down with the remains of an apricot. They reconvened upon a stump and looked about themselves.

“It's a good place to land,” the foundress said in her sweet soprano, examining the first rough maps that the scouts brought back. There were plenty of caterpillars, oaks for ink galls, fruiting brambles, and no signs of other wasps. A colony of bees had hived in a split oak two miles away. “Once we are established we will, of course, send a delegation to collect tribute.

“We will not make the same mistakes as before. Ours is a race of explorers and scientists, cartographers and philosophers, and to rest and grow slothful is to die. Once we are established here, we will expand.”

It took two weeks to complete the nurseries with their paper mobiles, and then another month to reconstruct the Great Library and fill the pigeonholes with what the oldest cartographers could remember of their lost maps. Their comings and goings did not go unnoticed. An ambassador from the beehive arrived with an ultimatum and was promptly executed; her wings were made into stained-glass windows for the council chamber, and her stinger was returned to the hive in a paper envelope. The second ambassador came with altered attitude and a proposal to divide the bees’ kingdom evenly between the two governments, retaining pollen and water rights for the bees — “as an acknowledgment of the preexisting claims of a free people to the natural resources of a common territory,” she hummed.

The wasps of the council were gracious and only divested the envoy of her sting. She survived just long enough to deliver her account to the hive.

The third ambassador arrived with a ball of wax on the tip of her stinger and was better received.

“You understand, we are not refugees applying for recognition of a token territorial sovereignty,” the foundress said, as attendants served them nectars in paper horns, “nor are we negotiating with you as equal states. Those were the assumptions of your late predecessors. They were mistaken.”

“I trust I will do better,” the diplomat said stiffly. She was older than the others, and the hairs of her thorax were sparse and faded.

“I do hope so.”

“Unlike them, I have complete authority to speak for the hive. You have propositions for us; that is clear enough. We are prepared to listen.”

“Oh, good.” The foundress drained her horn and took another. “Yours is an old and highly cultured society, despite the indolence of your ruler, which we understand to be a racial rather than personal proclivity. You have laws, and traditional dances, and mathematicians, and principles, which of course we do respect.”

“Your terms, please.”

She smiled. “Since there is a local population of tussah moths, which we prefer for incubation, there is no need for anything so unrepublican as slavery. If you refrain from insurrection, you may keep your self-rule. But we will take a fifth of your stores in an ordinary year, and a tenth in drought years, and one of every hundred larvae.”

“To eat?” Her antennae trembled with revulsion.

“Only if food is scarce. No, they will be raised among us and learn our ways and our arts, and then they will serve as officials and bureaucrats among you. It will be to your advantage, you see.”

The diplomat paused for a moment, looking at nothing at all. Finally she said, “A tenth, in a good year — ”

“Our terms,” the foundress said, “are not negotiable.”

The guards shifted among themselves, clinking the plates of their armor and shifting the gleaming points of their stings.

“I don't have a choice, do I?”

“The choice is enslavement or cooperation,” the foundress said. “For your hive, I mean. You might choose something else, certainly, but they have tens of thousands to replace you with.”

The diplomat bent her head. “I am old,” she said. “I have served the hive all my life, in every fashion. My loyalty is to my hive and I will do what is best for it.”

“I am so very glad.”

“I ask you — I beg you — to wait three or four days to impose your terms. I will be dead by then, and will not see my sisters become a servile people.”

The foundress clicked her claws together. “Is the delaying of business a custom of yours? We have no such practice. You will have the honor of watching us elevate your sisters to moral and technological heights you could never imagine.”

The diplomat shivered.

“Go back to your queen, my dear. Tell them the good news.”

It was a crisis for the constitutional monarchy. A riot broke out in District 6, destroying the royal waxworks and toppling the mouse-bone monuments before it was brutally suppressed. The queen had to be calmed with large doses of jelly after she burst into tears on her ministers’ shoulders.

“Your Majesty,” said one, “it's not a matter for your concern. Be at peace.”

“These are my children,” she said, sniffling. “You would feel for them too, were you a mother.”

“Thankfully, I am not,” the minister said briskly, “so to business.”

“War is out of the question,” another said.

“Their forces are vastly superior.”

“We outnumber them three hundred to one!”

“They are experienced fighters. Sixty of us would die for each of theirs. We might drive them away, but it would cost us most of the hive and possibly our queen — ”

The queen began weeping noisily again and had to be cleaned and comforted.

“Have we any alternatives?”

There was a small silence.

“Very well, then.”

The terms of the relationship were copied out, at the wasps’ direction, on small paper plaques embedded in propolis and wax around the hive. As paper and ink were new substances to the bees, they jostled and touched and tasted the bills until the paper fell to pieces. The wasps sent to oversee the installation did not take this kindly. Several civilians died before it was established that the bees could not read the Yiwei dialect.

Thereafter the hive's chemists were charged with compounding pheromones complex enough to encode the terms of the treaty. These were applied to the papers, so that both species could inspect them and comprehend the relationship between the two states.

Whereas the hive before the wasp infestation had been busy but content, the bees now lived in desperation. The natural terms of their lives were cut short by the need to gather enough honey for both the hive and the wasp nest. As they traveled farther and farther afield in search of nectar, they stopped singing. They danced their findings grimly, without joy. The queen herself grew gaunt and thin from breeding replacements, and certain ministers who understood such matters began feeding royal jelly to the strongest larvae.

Meanwhile, the wasps grew sleek and strong. Cadres of scholars, cartographers, botanists, and soldiers were dispatched on the river in small floating nests caulked with beeswax and loaded with rations of honeycomb to chart the unknown lands to the south. Those who returned bore beautiful maps with towns and farms and alien populations of wasps carefully noted in blue and purple ink, and these, once studied by the foundress and her generals, were carefully filed away in the depths of the Great Library for their southern advance in the new year.

The bees adopted by the wasps were first trained to clerical tasks, but once it was determined that they could be taught to read and write, they were assigned to some of the reconnaissance missions. The brightest students, gifted at trigonometry and angles, were educated beside the cartographers themselves and proved valuable assistants. They learned not to see the thick green caterpillars led on silver chains, or the dead bees fed to the wasp brood. It was easier that way.

When the old queen died, they did not mourn.

By the sheerest of accidents, one of the bees trained as a cartographer's assistant was an anarchist. It might have been the stresses on the hive, or it might have been luck; wherever it came from, the mutation was viable. She tucked a number of her own eggs in beeswax and wasp paper among the pigeonholes of the library and fed the larvae their milk and bread in secret. To her sons in their capped silk cradles — and they were all sons — she whispered the precepts she had developed while calculating flight paths and azimuths, that there should be no queen and no state, and that, as in the wasp nest, the males should labor and profit equally with the females. In their sleep and slow transformation they heard her teachings and instructions, and when they chewed their way out of their cells and out of the wasp nest, they made their way to the hive.

The damage to the nest was discovered, of course, but by then the anarchist was dead of old age. She had done impeccable work, her tutor sighed, looking over the filigree of her inscriptions, but the brilliant were subject to mental aberrations, were they not? He buried beneath grumblings and labors his fondness for her, which had become a grief to him and a political liability, and he never again took on any student from the hive who showed a glint of talent.

Though they had the bitter smell of the wasp nest in their hair, the anarchist's twenty sons were permitted to wander freely through the hive, as it was assumed that they were either spies or on official business. When the new queen emerged from her chamber, they joined unnoticed the other drones in the nuptial flight. Two succeeded in mating with her. Those who failed and survived spoke afterward in hushed tones of what had been done for the sake of the ideal. Before they died they took propolis and oak-apple ink and inscribed upon the lintels of the hive, in a shorthand they had developed, the story of the first anarchist and her twenty sons.

Anarchism being a heritable trait in bees, a number of the daughters of the new queen found themselves questioning the purpose of the monarchy. Two were taken by the wasps and taught to read and write. On one of their visits to the hive they spotted the history of their forefathers, and, being excellent scholars, soon figured out the translation.

They found their sisters in the hive who were unquiet in soul and whispered to them the strange knowledge they had learned among the wasps: astronomy, military strategy, the state of the world beyond the farthest flights of the bees. Hitherto educated as dancers and architects, nurses and foragers, the bees were full of a new wonder, stranger even than the first day they flew from the hive and felt the sun on their backs.

“Govern us,” they said to the two wasp-taught anarchists, but they refused.

“A perfect society needs no rulers,” they said. “Knowledge and authority ought to be held in common. In order to imagine a new existence, we must free ourselves from the structures of both our failed government and the unjustifiable hegemony of the wasp nests. Hear what you can hear and learn what you can learn while we remain among them. But be ready.”

It was the first summer in Yiwei without the immemorial hum of the cartographer wasps. In the orchards, though their skins split with sweetness, fallen fruit lay unmolested, and children played barefoot with impunity. One of the villagers’ daughters, in her third year at an agricultural college, came home in the back of a pickup truck at the end of July. She thumped her single suitcase against the gate before opening it, to scatter the chickens, then raised the latch and swung the iron aside, and was immediately wrapped in a flying hug.

Once she disentangled herself from brother and parents and liberally distributed kisses, she listened to the news she'd missed: how the cows were dying from drinking stonecutters’ dust in the streams; how grain prices were falling everywhere, despite the drought; and how her brother, little fool that he was, had torn down a wasp nest and received a faceful of red and white lumps for it. One of the most detailed wasp's maps had reached the capital, she was told, and a bureaucrat had arrived in a sleek black car. But because the wasps were all dead, he could report little more than a prank, a freak, or a miracle. There were no further inquiries.

Her brother produced for her inspection the brittle, boiled bodies of several wasps in a glass jar, along with one of the smaller maps. She tickled him until he surrendered his trophies, promised him a basket of peaches in return, and let herself be fed to tautness. Then, to her family's dismay, she wrote an urgent letter to the Academy of Sciences and packed a satchel with clothes and cash. If she could find one more nest of wasps, she said, it would make their fortune and her name. But it had to be done quickly.

In the morning, before the cockerels woke and while the sky was still purple, she hopped onto her old bicycle and rode down the dusty path.

Bees do not fly at night or lie to each other, but the anarchists had learned both from the wasps. On a warm, clear evening they left the hive at last, flying west in a small tight cloud. Around them swelled the voices of summer insects, strange and disquieting. Several miles west of the old hive and the wasp nest, in a lightning-scarred elm, the anarchists had built up a small stock of stolen honey sealed in wax and paper. They rested there for the night, in cells of clean white wax, and in the morning they arose to the building of their city.

The first business of the new colony was the laying of eggs, which a number of workers set to, and provisions for winter. One egg from the old queen, brought from the hive in an anarchist's jaws, was hatched and raised as a new mother. Uncrowned and unconcerned, she too laid mortar and wax, chewed wood to make paper, and fanned the storerooms with her wings.

The anarchists labored secretly but rapidly, drones alongside workers, because the copper taste of autumn was in the air. None had seen a winter before, but the memory of the species is subtle and long, and in their hearts, despite the summer sun, they felt an imminent darkness.

The flowers were fading in the fields. Every day the anarchists added to their coffers of warm gold and built their white walls higher. Every day the air grew a little crisper, the grass a little drier. They sang as they worked, sometimes ballads from the old hive, sometimes anthems of their own devising, and for a time they were happy. Too soon, the leaves turned flame colors and blew from the trees, and then there were no more flowers. The anarchists pressed down the lid on the last vat of honey and wondered what was coming.

Four miles away, at the first touch of cold, the wasps licked shut their paper doors and slept in a tight knot around the foundress. In both beehives, the bees huddled together, awake and watchful, warming themselves with the thrumming of their wings. The anarchists murmured comfort to each other.

“There will be more, after us. It will breed out again.”

“We are only the beginning.”

“There will be more.”

Snow fell silently outside.

The snow was ankle-deep and the river iced over when the girl from Yiwei reached up into the empty branches of an oak tree and plucked down the paper castle of a nest. The wasps within, drowsy with cold, murmured but did not stir. In their barracks the soldiers dreamed of the unexplored south and battles in strange cities, among strange peoples, and scouts dreamed of the corpses of starved and frozen deer. The cartographers dreamed of the changes that winter would work on the landscape, the diverted creeks and dead trees they would have to note down. They did not feel the burlap bag that settled around them, nor the crunch of tires on the frozen road.

She had spent weeks tramping through the countryside, questioning beekeepers and villagers’ children, peering up into trees and into hives, before she found the last wasps from Yiwei. Then she had had to wait for winter and the anesthetizing cold. But now, back in the warmth of her own room, she broke open the soft pages of the nest and pushed aside the heaps of glistening wasps until she found the foundress herself, stumbling on uncertain legs.

When it thawed, she would breed new foundresses among the village's apricot trees. The letters she received indicated a great demand for them in the capital, particularly from army generals and the captains of scientific explorations. In years to come, the village of Yiwei would be known for its delicately inscribed maps, the legends almost too small to see, and not for its barley and oats, its velvet apricots and glassy pears.

In the spring, the old beehive awoke to find the wasps gone, like a nightmare that evaporates by day. It was difficult to believe, but when not the slightest scrap of wasp paper could be found, the whole hive sang with delight. Even the queen, who had been coached from the pupa on the details of her client state and the conditions by which she ruled, and who had felt, perhaps, more sympathy for the wasps than she should have, cleared her throat and trilled once or twice. If she did not sing so loudly or so joyously as the rest, only a few noticed, and the winter had been a hard one, anyhow.

The maps had vanished with the wasps. No more would be made. Those who had studied among the wasps began to draft memoranda and the first independent decrees of queen and council. To defend against future invasions, it was decided that a detachment of bees would fly the borders of their land and carry home reports of what they found.

It was on one of these patrols that a small hive was discovered in the fork of an elm tree. Bees lay dead and brittle around it, no identifiable queen among them. Not a trace of honey remained in the storehouse; the dark wax of its walls had been gnawed to rags. Even the brood cells had been scraped clean. But in the last intact hexagons they found, curled and capped in wax, scrawled on page after page, words of revolution. They read in silence.

Then —

“Write,” one said to the other, and she did.

The Lamp at the Turning

For ten years the streetlamp on the corner of Cooyong and Boolee kept vigil with the other lamps along the road. They were surrogate moons for an age when the moon itself was too distant and dim to guide travelers in the night, and they performed their duties faithfully and with pride in their high purpose. With the rest of its battalion, the streetlamp opened its one eye when night fell and shut it in the gray hours of morning. When it rained and water pooled in the gutter it could sometimes see itself, swan-necked and orange and not, it thought, unlovely.

Besides the quiet presence of the other lamps, it had for company a sea gull who would perch on its head and gossip about his chicks and in-laws and the rubbish heaps he had visited. Sometimes a migrant with brilliant feathers would bring news from far-off countries. There was very little the streetlamp wanted that it did not have.

One morning in autumn, as the leaves were beginning to crisp and curl, the streetlamp saw a young man in a red jacket walking along Boolee. It knew the people who passed it every day juggling cell phones and briefcases, dragging groceries, jogging, and it had seen him often before, but this time it noticed the sunlight flashing off the facets of his watch and glasses and the electric currents that oscillated through and around him, sinoatrial node to atrioventricular node, nerve to nerve, silver oxide battery to shivering grain of quartz. It pondered his fluttering damp hair and fluted ears and how he held himself with the careful gravity of the young pretending to be old. After he vanished from sight the streetlamp found itself hoping he had forgotten a book on the kitchen table or left the stove on, so he would turn back and it could watch him a few minutes longer.

In the park across the street the elms and oaks were browning at their tips; magpies conferred and conspired in the grass. Now and then a car or bicycle chortled by, ripping the air with its wheels. None of these things interested the streetlamp any more. It was impatient for the evening and the migration of office workers and clerks homeward, the young man among them.

It lived now for the moment early in the morning when he hurried up Boolee, his shirt neat, his hair combed to velvet, and for the moment in the afternoon or evening when his shadow preceded him down Cooyong. The night and day seemed miserably long, the other streetlamps dull and unfeeling. Even the conversation of the gull, when he dropped by, became tiresome.

For a month the streetlamp marked its mornings and evenings by his footsteps. It wanted him to meet its orange eye and understand that it loved him with every wire and soldered synapse of its being. Instead of snapping to attention with the rest of the lamps, it waited until it saw him before it flickered on. Though he worked long hours in the office and came home at irregular times, the streetlamp always watched for him. When he passed he would glance at it with curiosity but without slowing his step.

Finally, one night when he had stayed at the office until seven, he paused beneath the streetlamp, which had lit up as soon as it saw him. He put his hand on its metal post and said, “You wait for me every day, don't you?”

The streetlamp thought it would short out for happiness. It watched him go with brightness in its heart, and long after the heat of his hand had dissipated it remembered its shape and pressure.

He didn't stop again after that, but when he passed by he nodded at it as though to say hello, and sometimes he would smile. Sometimes the streetlamp winked at him. There were mutters of disapproval along the street, and even the sea gull said it was a bad business, but nothing could perturb the streetlamp's profound joy.

One evening the young man was not alone. A woman with hair braided to her waist walked beside him, and she looked at him the way the streetlamp looked at him, as if she wished a spark would jump between them. The streetlamp felt a black, sputtering anger in its circuits.

They stopped on the corner under the streetlamp.

“This light always goes on when I walk by,” he said. “See?”

She tilted her head to meet the streetlamp's gaze. On the surface of her pupils it saw two points of orange light, and below that, secret and sad, a loneliness like its own.

“It must be in love with you,” she said.

“That's cute.”

They went on, their heads bent toward each other, talking but not touching. Once she glanced back at the streetlamp.

The winter went by quickly. The streetlamp grew icicles and lost them but hardly felt the cold. Twice each day it saw the man in the red jacket turn the corner, and that was all the summer it wanted. If he coughed on the sharpness of the air, or if his face paled in the wind, it only made him more beautiful to the lamp, and it flung its light lovingly around his shoulders, as though to warm him.

Then a day came when the young man should have gone to work but did not. He did not pass the streetlamp in the evening, nor the next day. It waited for him, keeping its sodium tubes dark well past midnight and bright well past noon, but he did not appear.

A few weeks later, the woman came and stood under the streetlamp, her hands in the pockets of her leather skirt, her green scarf shivering in the wind. Her eyes were smudged and dark.

“He's gone,” she said. “New job, different town. I thought you might want to know.”

She touched the base of the streetlamp with one gloved finger and was gone.

Spring came, and the furred buds along the branches of trees burst softly into bloom. One day the town's electric company drove their van up the street and parked under the streetlamp, which had stopped lighting up at all.

“This one's a mess,” one of the electrical workers said, examining the paper on his clipboard. “Been erratic all winter.”

“What's it done?”

“Turned on and off at odd times.”

“That shouldn't be possible.”

“I want a look at the photoelectric control.”

They removed the panel at the base of the street light and cut out the small box from its entangling wires. A small sigh moved the air, but it was impossible to say where it came from, whether the watching streetlamps or the trees. The electrical workers did not hear.

“You're right, it's dead.”

“Got a spare?”

“Right here.”

They scraped, knotted, snipped, then gathered their red-handled tools and left.

When the sunlight slanted and faded into darkness, all the lights on the street flashed to life at once, like a string of stars fallen to earth. A sea gull rowed by on black-tipped wings, but not finding anyone it knew, flew on.

Tiger in the BSE

There was once a tiger in Mumbai, a Kshatriya and a ruthless trader of stocks, who lived in a glossy high-rise the color of the sea. His suits of slick poplin and seersucker were confected by two tailors in Milan; his bath was cut from marble as rich as soap, and always drawn warm and fragrant for him at the end of each day; and his suppers, which threw the meat markets into an uproar, were prepared under the hands of some of the finest cooks from Mangalore and Chengdu. He had, in short, the kind of life that any well-bred tiger could hope to have. But he lacked one thing, and it made him pace between the red walls of his living room and bite the pads of his paws.

He went to the house of an old friend, where he and his trading tips were always welcome, and said, “Brother, I have no mother or father to help me in this matter, and no family except my friends. For the sake of the tricks we played in school, for the beatings I took for you, will you help me find a bride?”

“My sisters are all spoken for,” the man said quickly. But seeing his whiskers quiver in distress, said, “Nevertheless I can inquire for you. What sort of bride are you looking for?”

Loss, with Chalk Diagrams

Never before in her life had Rebekah Moss turned to the rewirers, not as a tight-mouthed girl eavesdropping by closed doors on her parents’ iceberg drift toward divorce, nor after she heard with bowed head, her body as blushingly full as a magnolia bud, the doctor describing the scars that kept her from having Dom's child. She took few risks and accepted all outcomes with equanimity. But when her old friend Linda was found beneath a park bridge in Quebec with her wrists slit lengthwise to the bone, leaving no note, no whisper of explanation, she hesitated only a moment before linking to the rewiring center. Saturday next was the first available appointment, a silvery voice informed her, and she took it. When she ended the call she wrapped her arms around her legs and tilted back and forth, blinking hard, her own breathing a foil rustle in her ears.

She had been twelve years old when rewiring was first approved for use on a limited clinical population. The treatment involved a brew of sixteen neurotoxins finely tuned to leave normal motor, memory, and cognitive processes intact, burning out only those neural pathways associated with grief and trauma. It was recognized as a radical advancement in medicine, and the neuroscientists involved in its development had been decorated with medals, presidential visits, and a research foundation in their names.

Her family supported her choice, of course. They pressed lemon tea and tissues and bitter chocolate upon her while she stumbled through the week, her whole world gone faint and gray and narrow. The sky seemed always clouded over, though she knew there was sunlight. She could not eat by herself. Dom fed her soup by hand and patted her rather awkwardly as she sobbed, both of them embarrassed by her access of sorrow. It was the only time in their marriage that she had cried.

She and Linda had grown up together, small and very different but fiercely loyal, as children can be. Linda had been her first real friend, all temper and rainstorms and rainbows, quick to scrape, to bleed, to run, to tumble, to climb. Her whole head of copper curls trembled when she laughed, and she had laughed often. She hummed pop songs off-key. She danced. Rebekah could often see the passions singing inside her, darkening and flushing and paling her cheeks, contorting her mouth, dilating or slitting her eyes. Sometimes Linda would blow up a squall — over Darrell, a thin boy with scarred and freckled knees who held Rebekah's hand once, by accident, and Linda's twice; over Rebekah's remark to another friend about Linda's father's drinking; over classroom prizes and movies they loved or loathed — but as Rebekah didn't fight back, only listening with a pale calm, these were quickly over, forgiven and forgotten.

They used to chalk coded messages for each other on the blacktop behind school, though chalk and chalkboards had long since vanished from classrooms, because they had read about it and wanted to try. They had mixed, colored, and molded the sticks out of plaster of Paris and paint. Once the sticks had been written to nubs, the girls crushed them to powder between their fingernails. It was a private art. Every stroke on the classroom screen, every voicelink, every comma and misspelling sent through the flow was documented and preserved perfectly for the ages, but the rain wiped clean their messages to each other and let them have secrets.

In high school the two of them drifted apart, distracted variously by clubs, boys, academic distinctions, other friends. Rebekah absorbed herself in the quiet pleasure of her French horn and regional orchestras; Linda realized a passion for biology, herpetology in particular, and acquired a lime-green lizard named Otto that she would smuggle to school in her pocket. Linda began to kiss boys; Rebekah only looked sidelong at one or two who made her glow inside when they laughed, and never spoke.

In the spring of their junior year, Linda's mother died. No one was quite sure why. She had seemed healthy, although Linda said once, when pressed, that it was cancer and she didn't want to talk about it.

The funeral was private. Linda vanished from school for several weeks, reappearing in caked makeup with dark, defiant eyes. She was prone to bursting into tears. The guidance counselor and several teachers pointed out to her that, as a bereaved minor, she was a prime candidate for rewiring. Treatment would allow her to focus on her schoolwork and college applications, they said: her grades had become erratic. They were worried about her future. Moreover, her outbursts were disturbing the other students.

Linda refused. After the fifth or sixth recommendation that she apply for rewiring, there was a firm suggestion that she take a year off from school, at which point she started shouting at the counselor and had to be restrained. Within days the whole school knew.

By that time, Rebekah was too distant from Linda to hear all of what was happening, but one day at lunchtime she brushed into her in the hall and was unwillingly drawn into a conversation about Mrs. Lubrick, for whom Linda felt a deep disdain. Linda pressed close; Rebekah could see the tiny, fine cracks in her foundation. There was a faint smell of alcohol on Linda's breath.

“She thinks it's something you can snip off, like hair or nails,” Linda said. “That you can chop off loss without losing anything. But it's mine and I want it. It's horrible but it's mine.”

Her eyes were narrowed, her lips badly chapped.

“My dad had people come and take away her clothes in bags. All of it. It was like watching someone slice open the family and pull out all the organs. I didn't want him to, but he couldn't stand it, her things lying around. I'm keeping every minute of this hurting. I'm keeping it.”

She hugged herself, the oversized sweater lapping over her hands, and glared. Rebekah shrugged and turned away.

By the beginning of their senior year Linda discovered a reservoir of manic energy, and when spring came around she had been accepted to five of her seven schools. Rebekah applied to one and was accepted there, as she had known she would be.

It was at Grierson, three years after she had last spoken to Linda, that she opened her mailbox one morning to find a postcard with a picture of a marbled library, a California postmark, and a barely legible scrawl: Dear Rebekah, I know we didn't talk much in high school, but I was thinking of you lately and looked up your address. I am doing well. Do you remember the chalk? Write to me if it's not too silly for you.

After thinking for two days, Rebekah dug up a stamp, a pen, and a card from the depths of the university museum shop — postal correspondence was an anachronism then, kept running by advertising, nostalgia and the government's good graces — and scribbled in large letters shaky with disuse: Dear Linda, happy to hear from you. What has your life been like? I am awful at postcards. Sorry.

In reply she received a dried dahlia in a blue envelope with the note: Charming, dahling. Rebekah held the crisping flower in her palm, the desk lamp lighting the petals like a paper lantern, and remembered the feeling of pastel dust on her fingers and the scrape of asphalt on her skin. Then she set the dahlia on her desk and uncapped her antique pen.

Dear Linda, tomorrow I am graduating from Grierson Mech E, cum laude. I have a job in Albany this fall making wireframes for printed engine parts.

Dearest Rebekah, I'm writing from Jakarta. Reporting for private flow feeds as well as the Times of Singapore. Eating jackfruit and rambutan, which is cheap and fresh here. Traffic is like being strangled. I bike sometimes. If this card is black when it reaches you, that's Jakarta smog. Rob left a few weeks ago, and I am lonely. Your last card came at the perfect time.

Dear Linda, this is the house we're moving into next month. I don't like the wooden shingled sides — they're green and brown from too much rain — but it is bright inside. I can make a life here, I think. All is well. Do send me your new addresses when you move. It's not easy keeping track of you.

My dear Rebekah, congratulations on the wedding, and Dom, and all. Are you still playing in your community orchestra? Is that the same horn you had in high school? They don't wear out, right? Love from London.

Dear Linda, thank you for the violin recordings. Where did you find the violinist? I play them at work when my equations stop making sense. Sometimes the noise from the machining rooms downstairs rattles my brain. Your music is a sweet relief. Send more.

Rebekah, I have ditched the last boy — or he ditched me — again. Too fond of blondes. Had to move out, now staying with a friend.

Dear Linda, we saw the doctor yesterday. It is not possible, he says.

Rebekah stacked the postcards in a small tin painted with daffodils, where year by year they faded. By mutual unspoken agreement they continued to write to each other, avoiding calls, flow feeds, emails, everything permanent and certain. It seemed right that their correspondence be an ephemeral thing, somehow, though everything else in Rebekah's life was heavy with deliberation, immense and secure. Dom was the only man she ever dated, and they had married after a brief courtship as careful and formal as a game of chess. They read the news on the glass of their breakfast table and kissed each other before leaving for work. They planted flowered borders of perennials. They did not travel.

It had been inevitable that the postal system would eventually collapse. On the morning that the last post office was shuttered, Rebekah scanned the news on the table and sighed. Then she linked to a node in Montreal, Linda's last known address, and left a tentative message inviting her to visit.

Linda arrived in a whirlwind of loss — lost paperwork, lost passport, lost lover, recently deceased father — her black hobnailed boots striking sparks from the pavement as she walked, her short hair waving like candle flames. She enumerated these losses to Rebekah in a rich rippling alto that sometimes shook with laughter and always gleamed with color, describing her four heartbreaks — Rob, Ajay, Chris, Max — each worse than the last; the three times she had been held up at knifepoint; the one time she had betrayed and the five times she had been betrayed; and for one shivering moment Rebekah saw her quiet happiness pale beside the coruscations of Linda's life.

Grief had written heavy lines on Linda's face. Despite her scars and bruises, her casualties, her innumerable losses, she had not applied for rewiring either. By then it was standard procedure, shading into the cosmetic. Rebekah's parents and most of her other relatives had been rewired. They had pushed Rebekah to apply after she learned she would never have a child, relenting only after six weeks of her pleasant, toneless insistence that she was fine. After all, she told Dom and her family, she had not lost anything.

To all appearances the procedure was a blessing. The suicide rate had dropped nationwide and in those developed countries that could afford to make rewiring available. It was becoming difficult to find songs about heartbreak on flowlines these days, Linda said. Tragedies were disappearing from theaters and screens. Sorrow was no longer a welcome and expected guest. “Except to me,” Linda said, sounding puzzled and proud. As they passed a hallway mirror, Rebekah was startled to see the contrast in their faces; she looked an entire decade younger than Linda, with fewer shadows, fewer lines, fewer softnesses and sinkings. And yet Linda had grown beautiful, richly and ripely beautiful, an awareness that pressed on Rebekah as inexorably as sunlight. It had been years since they last stood in the same room.

“You're so happy,” Linda broke out, over their dinner of salmon and asparagus, Dom smiling benignly at them. Her mouth twisted briefly. “You've lived so well.”

Then she had blushed, a familiar rose blooming in each cheek, and ducked her head, and complimented the food. The conversation veered to politics and immigration law. Linda was entangled in immigration court, having overstayed a complicated sequence of visas. She had traveled too often and lived in too many places, she said. Loved the wrong people, the right people, or too many people. Carried a piece of each place inside her. Sometimes a ring. Once, an unborn child. Her face flickered at that. It all played merry hell with your passport, she said. Her smile was fragile.

Dom brought out the raspberry tart, a silver cake trowel, and a stack of willow plates.

“A good immigration lawyer,” he suggested, piecing out the tart, but she shook her head.

“I had one,” Linda said. “I tried. It's over, really.”

Later, when she went out into the garden to smoke, Rebekah said to her, “You could let go of it all so easily.”

“The sadness? Perhaps.” Linda blew a billow of smoke. Smoking was another anachronism she had picked up; Rebekah wondered when, and why, and with whom.

“Think of how much lighter you'd be,” Rebekah said. “How peaceful you'd feel. You'd live longer.”

Linda laughed. “You're telling me to let go of my grief? You?” She tilted the glowing tip of her cigarette toward Rebekah. “You'll never have the children you want. That would break anyone's heart. But you didn't go for rewiring. Why not? Why not let go?”

Rebekah found she could not answer.

If she closed her eyes she could recall the clinic in crisp, hectic color. The room had been cream-colored, trimmed in pale green, and smelled faintly and cruelly of mother's milk. The stethoscope around the doctor's neck was also pale green. The barrage of scans and tests was over. It was all over. She had sat under the too-bright lights, looking at her hands, her ears full of the dull crash and roar of her blood. I'm very sorry, the doctor said, and she heard herself saying, No, no, it's quite all right. As she had said to Dom, and to her mother, and his, until the words were nonsense in her mouth. It's quite all right, she said, burying the bitterness inside herself, shrugging off the suggestion. No, no rewiring. It's all right.

The air still tasted bitter, under the odor of roses.

“As for me,” Linda said, “grieving makes me whole. Anything and anyone worth having is also worth wearing a scar for, if only on the inside.” She took a drag on the cigarette, and smoke flowered from her mouth.

“I don't understand.”

“Do you love that man? Dom? If he died, would you cry over him? Would you spend years looking for him in the morning and expecting his presence in every room of your house and feeling your heart crack each time you realize he's not there? Or would you go straight to the needles?”

“That's not a fair question,” Rebekah said, waving away the smoke. “He wouldn't want me to mourn.”

“No?”

“He doesn't want me to suffer.”

“You think there can be love without suffering? Having without losing?”

Rebekah looked at her friend, so troubled, so tired, so lovely. “Yes.”

“Would you mourn me?” Linda's eyes were large and luminous. “You're one of the few who still can.”

“If you died? You'd want me to be miserable for losing you?”

“I want to be remembered.” She dropped the cigarette in a spray of sparks and ground it beneath her toe. “I want to be a physical absence in a room. I want to be a void and an ache. I want to be remembered with sorrow, the way I remember so many other people now.”

“That seems selfish.”

“Perhaps.” Linda sighed. “There aren't that many people left to grieve, anyhow. Why haven't you gone for rewiring?”

The vivid, heavy smells of roses and cigarettes were making her dizzy. There were the boys she never kissed, too afraid to speak to them; the trips she had decided not to take; the jobs in other places she had turned down; the child she could not have. Instead of these things, she had Dom's love, a warm house, steady work as a propulsion engineer, and two evenings a week in an orchestra. She supposed she did not regret her choices. What did she have to grieve for, after all?

“I haven't lost very much, I guess.” She pressed her lips together.

“Just possibilities.”

Upstairs the bedroom windows filled with light, then darkened.

Linda extended a finger with a glittering drop of data on it. “Here, I brought this for you. I recorded it in Montreal.”

“What is it?”

“Freeman, French horn. Hard to find that kind of music these days. Don't listen to it now. It's late.”

She kissed Rebekah on the brow before she went, leaving a dusty mark.

Saturday came with terrible slowness. Rebekah could hardly find the strength to leave her bed. She recalled that evening vividly, the taste of butter and raspberry jam, the smell of tobacco smoke, the brush of dry, powdery lips against her forehead. Nothing in that evening had hinted at the horror of white bone and slashed muscle, and yet all of Linda's life seemed full of signs and portents, now that she was gone.

Rebekah barely noticed anything on her walk downtown. Before long she stood before the chrome and glass doors of the district's rewiring center, staring dully up at the silver-lettered signs and the office windows full of desks and blurred figures. Dom could not accompany her; he had been sweetly apologetic; he had to implement new protocols in the lab ahead of state deadlines.

Everything in the center was painfully gleaming and new, from the young man who greeted her at the desk, the crispness of college still on him, to the white leather sofas she was directed to. The interior was lit by a gentle but intense white light, enough to pierce through the fog in her head.

“Let me explain the procedure to you,” the doctor said. “We will be making eight injections into your insula, anterior temporal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and prefrontal cortex. You will be under general anesthesia for the entire operation. It should take three hours. We have not found significant side effects but a small number of patients have reported lethargy lasting a week, loss of appetite, lingering sadness, and feelings of confusion. Would you please sign here?”

First they shaved small squares on her scalp where the thin drills and then the needles would pass through. She watched dark strands of her hair fall into her lap, scattering over her white paper robe. Then they left her in a room to wait.

Rebekah sat alone on the bed, numb and cold, toying with the strange spiky shapes of her grief. Rather than listen to the unbearable symphony of beeping, chiming monitors, she pulled up the recording that Linda had given her.

It began with scraping chairs and indistinct voices, some swift French, some English. There was shuffling, and coughing, and silence. Then she heard a slender silver note, the winding of a hunting horn. Foxes and deer slid through the mist, tearing up the wet earth, followed by men and women and sleek hounds. The horn urged them on. The best of the hunters took aim and fired through the fog, but the bullet killed his lover instead of the deer.

She heard grief in the music, flashing like lightning beneath the silver notes. It had been a very long time since she had heard music like it. Her community orchestra was very good at light, pensive, or melancholy music, but when they tried the tragic, their performance rang empty. Freeman was something else altogether. She had missed that kind of music. It was a good gift.

Rebekah closed the file and raised her head to see two blue-scrubbed nurses approaching.

They were wiping and tying her arm for the anesthetic, the faces around her friendly and smiling, when she realized how jealous she had become of her black, broken grief. It hurt, but it was hers. That had also been a gift.

Wait, she wanted to say. I don't want this anymore. She opened her mouth, then closed it again. She told herself: You refused her. You don't deserve to grieve.

The needle slid beneath her skin.

You never learned how to lose someone.

A thick soft darkness swallowed her, a sinking without bottom, through which she swam ever deeper down. Somewhere rain fell and washed the pavement clean.

When she awoke, she was not in pain.

Ilse, Who Saw Clearly

Once, among the indigo mountains of Germany, there was a kingdom of blue-eyed men and women whose blood was tinged blue with cold. The citizens were skilled in clockwork, escapements, and piano manufacture, and the clocks and pianos of that country were famous throughout the world. Their children pulled on rabbit-fur gloves before they sat down to practice their etudes, for it was so cold the notes rang and clanged in the air. It was coldest of all in the town on the highest mountain, where there lived a girl called Ilse, who was neither beautiful nor ugly, neither good nor wicked. Yet she was not quite undistinguished, because she was in love.

One afternoon, when the air was glittering with the sounds of innumerable pianos, a stranger as stout as a barrel and swathed to his nosetip walked through the town, singing. Where he walked the pianos fell silent, and wheat-haired boys and girls cracked shutters into the bitter cold to peep at him. And what he sang was this:

Ice for sale, eyes for sale,

If your complexion be dark or pale

If your old eyes be sharp or frail,

Come buy, come buy, bright ice for sale!

Only his listeners could not tell whether he was selling ice or eyes, because he spoke in an odd accent and through a thick scarf.

He sang until he reached the square with its frozen marble fountain. The town had installed a clock face and a set of chimes in the ice, and now they were striking noon.

“Ice?” he said pleasantly to the crowd that had gathered. He unwound a few feet of his woolen cloak and took out a box. The hasp gave his mittens trouble, but finally it clicked open, and he raised the lid and held out the box for all to see. They craned their necks forward, and their startled breaths smoked the air.

The box was crammed with eyes.

There were blue eyes and green eyes and brown eyes, eyes red as lilies, golden as pollen; eyes like pickaxes and eyes like diamonds. Each eye had been carved and painted with enormous care, and the spaces between them were jammed with silk.

The stranger smiled at their astonishment. He unrolled a little more of his cloak and took out another box, and another, and then it was clear that he was really quite slender. He tugged his muffler past his mouth, revealing sunned skin and neat thin lips.

“The finest eyes,” he said to the crowd. “Plucked from the lands along the Indian Ocean, where the peacock wears hundreds in his tail. Picked from the wine countries, where they grow as crisp as grapes. Young and good for years of seeing! Old but ground to perfect clarity, according to calculations by the wisest mathematicians in Alexandria!” His teeth flashed gold and silver as he talked.

He ran his fingers through the eyes, holding this one to the light, or that. “Is this not pretty?” he said. “Is this not splendid? Try, my good grandmother, try.”

That old woman peered through eyes white with snow-glare at the gems in his hands. “I can't see them clearly,” she admitted.

“Well, then!”

“Lucia,” she said, touching her daughter's hand. “Find me a pair like I used to have.”

“How much?” Lucia said.

“For you, the first, a pittance. An afterthought. Her old eyes and a gold ring.”

“Done,” the old woman said. Lucia, frowning, fingered two eyes as blue as shadows on snow.

The stranger extracted three slim silver knives with ivory handles from the lining of his cloak. With infinite care and exactitude, barely breathing, he slid the first knife beneath the old woman's eyelid, ran the second around the ball, and with the third cut the crimson embroidery that tied it in place. Twice he did this. Then, in one motion, he slid her old eyes out of their hollows and slipped in the new. Her old blind eyes froze at once in his hands, ringing when he flicked them with a fingernail. He dropped them into his pockets and tilted her chin toward him.

“I can count your teeth,” the old woman said with wonder. “Your nose is thin. Your scarf is striped red and yellow.”

“A wonder,” someone said.

“A marvel of marvels.”

“A magician.”

“A miracle.”

She pulled off her mitten and gave him the ring from her left hand. “He's been dead twenty years,” she said to Lucia, who did not look happy. “I can see again. Clear as water. What a wonder.”

Then, of course, the stranger had to replace the shortsighted schoolteacher's eyes, after which the old fellow cheerfully snapped his spectacles in two; the neglectful eyes of the town council; six clockmakers’ strained eyes; crossed eyes; eyes bleared with snow light and sunlight; eyes that saw too clearly, or too deeply, or too much; eyes that wandered; eyes that were the wrong color.

When the sun was low and scarlet in the sky, the stranger announced that he would work no longer that day, for want of illumination. Half the town immediately offered him a bed and a roaring fire. But he passed that night and many more at the inn, where the fire was lower, colder, and less hospitable, and where, it was said unkindly, one's sleeping breath would freeze and fall like snow on the quilts. He ate cold soup and sliced meats in the farthest corner, answered all questions with a smile, and went to bed early.

After twelve days he bundled his boxes about him and left the town, his pockets sunken and swinging with gold. The townspeople watched as he goat-stepped down the steep trail until even their sharp new eyes could no longer distinguish him from the ice-bearded stones and the pines and the snow.

These new eyes, they found, were better than the old. The makers of escapements and wind-up toys found that they could do far more delicate work than before, and out of their workshops came pocket watches and pianos carved out of almond shells, marching soldiers made from bluebottles, wooden birds that flew and sang, mechanical chessboards that also played tippen, and other such wonders; and the fame of that town went out throughout the whole world.

Summer heard, in her house on the other side of the world, and came to see.

The first notice they had of her approach was a message in a blackbird's beak, then a couple red buds on the edges of twigs, and then she was there. Out of respect she had put on a few extra flowers this year. It was still cold — summer high in the mountains is like that — but the air was softer, the light gentler.

No one saw her courteous posies, however. A little before she arrived, their eyes had begun to blur, then blear, then melt. They saw each other crying and felt their own tears running down their faces, and for no reason at all except summer. Then they understood, and wept in earnest, but it was too late.

By summer's end everyone had cried out the new eyes. The workshops fell still and silent, and tools gathered tarnish on their benches. The hundreds of clocks around the town stopped, since no one could find their keys and keyholes to wind them up again. Only the pianos still rang out their frozen notes now and again, but the melodies were all in minor keys. The town was full of a cold, quiet grief.

Winter was coming, and they would have starved without Ilse, who hadn't sold her eyes. Her sweetheart had written atrocious poems to them, and although they were the same plain blue as anyone else's, she couldn't bear to part with them even for new eyes the colors of violets, blackberries, and marigolds. So she helped the town tend and bring in its meager harvests of beets and cabbage, and on Wednesdays she filled a sack with clocks and toys and went down the mountain to sell them at market, until there were none left. During the day her head swam with the pianos’ lugubrious complaints, and at night she ached in every bone.

“Mother,” she said, as they ate their bare breakfast together, “shouldn't someone go looking for the surgeon?”

“No one will find him.”

“What will you do if you never find your eyes?”

“We'll manage. We have you to see for us.”

“I'm going to look for him,” she said.

“Absolutely not.”

So Ilse packed up her summer clothes, a loaf of bread, two onions, and the fourteen silver coins her mother kept in a jar on the shelf, and the next day she set off down the mountain.

In all her sixteen years, she had never strayed beyond the market in the shadow of the mountain, where the town's clocks and pianos were sold. But now she passed town after town, few of which she knew, and bridges, and streams, and meadows stained with the dregs of summer, and now trees that did not stand as straight as soldiers but spread their shoulders broad and wide. She climbed up one of these as night fell, and tucked her head against her knees, and slept.

A soft noise, like paper or feathers, woke her in the middle of the night. Ilse opened her eyes in fear, expecting robbers and thieves, but saw nothing. Still she was full of dread. She thought of the silver she had stolen, and her sightless mother in a silent house, and her sweetheart, lonely and wondering. She thought of the long road ahead of her, with likely failure at its end, and shivered. For where could she begin to look?

“You are thinking too loud,” someone said close to her ear. She nearly fell out of the tree. Next to her, an old crow shifted from foot to foot, cleared its throat, and spat.

“You can talk?”

“Only when people's thoughts are so noisy I can't sleep.” It sighed. “What would it take to quiet down your brain?”

“I am looking for my townsmen's eyes.”

“Eyes!” The crow whistled. “A treat, a delectable treat. I should follow you.”

Ilse snatched sideways, swiping a bit of dark down between her fingers. The crow tumbled out of the tree with a screech.

“You'll do no such thing,” she said.

“Peace, peace.” A wing brushed her brow. “You'll find what you're looking for. You'll find your sight, and theirs. And you'll not like what you see when you see the world truly, too-quick girl with the odor of onions.”

He flapped his way to a higher branch; she could hear him combing out his rumpled feathers. “I don't take kindly to being grabbed at, onion girl.”

“Just let me find what I'm looking for,” she said, and shut her eyes. Afterwards, but for the bit of down stuck to her clothes, she could not say whether she had dreamt it all.

On the third day, as she trudged down the road that went nowhere she knew, she met a flock of spotted goats with yellow bells about their necks, and then their shepherd, who was chewing a stalk of grass. He greeted her, and she asked with no great hope whether he'd heard of a peddler of eyes.

“Yes, miss,” he said. “Walk a little farther, until you reach a village with sunflowers around it, and go down the street to the last house. My daughter is home, and she knows much more about your magician than I do.”

Ilse thanked him and went on. The village ringed by sunflowers was smaller and muddier than her own, and the road ended at the smallest and muddiest house. The cat on the roof had only half his coat, as he had been a fierce warrior in his day, but he opened one eye and yawned at her. A young woman opened the door. Asked about the peddler, she smiled and winked her eyes one after the other. One of them was a shade greener than the other.

“I lost this one falling out of a window. My father and I waited four years before the good man came back. We had nothing to pay him with, at least nothing worth it, and I would have gladly taken a grandmother's cataract. But he said I was a lovely girl and picked out a greener eye than my first for me. A sweet soul.”

“He left my village blind.”

“You must be mistaken. He wouldn't do such a thing.”

“He has three silver knives with ivory hafts, with ivy engraved in the ivory. His skin is dark and his nose is sharp.”

“Well,” the goatherd's daughter said. “Well. He does look like that. And he does have three knives. But I really don't think — ”

“How can I find him?”

“Now, that's tricky. That will take a little explanation. But you're in no rush, are you? He doesn't travel quickly, and you don't look like you've eaten yet today.” She hewed a generous piece of brown bread for Ilse and poured out a bowl of cream for her, as well as a bowl of milk for the cat.

“I still think you're wrong somewhere. Surely he wouldn't. So kind.”

Ilse ate the bread and drank the cream so fast she left a crumb on her cheek and a pale spatter on her chin.

“Now,” the goatherd's daughter said presently, “you'll be going to the city. If you unraveled today down the road, you'd find the city at the end of next week. There are three towers at the corners of the city, with three broad streets between them, and where the streets meet is a brick square. Ask in the square where your magician might be. Someone there will know more.

“But you're not taking the road in those clothes, are you?”

Ilse was suddenly aware of how heavy and hot her woolen summer smock and rabbit-fur cloak were, and how strongly they reeked of onions.

“Let me find you something lighter. You can leave those here, for when you return.”

So Ilse exchanged her fur and wool for an armful of patched but comfortable linen, put a piece of bread and a slice of cheese in her pocket, and continued on her way. Now and then she passed a farm cart creaking on its way. Now and then, with a nod from the driver, she climbed into one of those carts and rested. She came upon a few crows pecking in the dust, but though she greeted them politely, they never answered.

The longer she traveled, the closer together grew the villages and fields. She was tired of the road and the yellow dust that lay in a film on her mouth, and she thought many times of her soft bed at home, and the color of her sweetheart's hair, and the air as pure as snow. Sometimes she considered turning around, but she never did. After wearing out her shoes by the thickness of seven days, she saw, black against the evening, three towers as formidable as teeth, and that was the city.

A soldier in fine scarlet-and-cream stood to attention at the gate, which was barred. He had a silver spear in his hand and silver mail beneath his tabard.

“It's past sunset,” he said, frowning at her through his helmet. “No one enters or exits the city at night. Go home.”

She said, “My home is in the mountains, but I've come looking for a magician, a doctor, who can take the eyes out of your head and put them in again. He took all the eyes out of our town.”

“I've heard of such a doctor,” said the soldier. “He mended my fourth cousin's weak eyes, years ago. But you can't mean him. He wouldn't do such a thing.”

“Perhaps it was unintended.”

“You'd do well to ask in the square tomorrow. Tomorrow, mind you. I cannot let you through.” He held his spear a little straighter. “Unless you can show me something as bright as sunlight. That might fool me for a little while.”

“I only have a little silver,” she said, patting her pockets. But they were empty.

“Moonlight will do.”

“No, I have nothing. I left my silver in my smock, and I left my smock at a goatherd's cottage, and that's a week's walking.”

The soldier huffed into his moustache. “What a foolish girl you are.” He took a key from his belt and opened a low door in the gate, just tall enough for her to slip through. “I have a little one your age, just as silly as you. You'd feed yourself to wolves if I kept you outside. Hurry up, won't you. And stay out of trouble.”

“Thank you,” Ilse said, and he shut and locked the door behind her.

Here and there the flame in a lamppost flickered and swayed. There were many more streets than she had expected, running every which way. Uncertain of what to do, she went back and forth, past dark windows and bolted doors; open doors with laughter, hectic music, and light spilling out of them; past rubbish in the gutters and pools of water shining in the dark. Shadows slid past her, silent and purposeful. She felt unseen eyes following her.

At last, lost and dispirited, she peered into a shop window and saw a vitrine lined with pocket watches and the pale faces of tall clock cases in the dimness beyond. Some of them looked familiar. She pressed her nose to the gold-lettered glass, wondering if she knew the hands that had made them. She wanted very much to touch them, but the door was locked.

There was nowhere else she could go. She sat down in the doorway and put her head in her hands and, unwillingly, fell asleep.

If strange hands rifled her pockets while she slept, they found nothing, and she did not know. When she woke, it was morning. An old man with a broom was standing over her, displeased.

“Well, get along now,” he said. “Go on.” He held the shop door open and swept a little dirt over her, then tried to sweep her off the step.

“Please, which way to the square?”

“Which way to the square?” The shopkeeper stared. “Are you mad?”

“I came into the city yesterday,” she said.

“With no place to stay? You are mad.”

“Won't you tell me?”

“Never let it be said I was uncharitable toward the insane,” the shopkeeper said. He disappeared into the shop — a bell jangled inside — and just as she decided to leave, reappeared with a small stale cake.

“There you go,” he said. “Down the lane, a left, a right, a right, a left, a right, two more lefts, and you're there.” And he went back into the shop.

The square was broader than she expected, and busier, lively with stalls and carts and striped awnings, the glitter of gold and silver on tables, the odors of fruit and fish and spices, the squabble of bargainers and women shouting apples.

Weaving her way through the tables and crowds, dazzled and bewildered, she stopped beside a table set with magnificent glass apparatuses: telescopes, periscopes, beakers, loupes, spiral condensers, burning glasses, spectacles. Behind a towering stack of old books sat the glassblower, his nose in a book, a mole at the tip of his nose. She asked whether he knew the magician.

“Of course! Of course!” he snorted.

“Where can I find him?”

“Why, he's marrying our Queen next month! Only,” he said, and winked, “no one knows that it's him, our peripatetic physician, our humble expeller-of-drusen, ablator-of-sties. Word is she's betrothed to a Solomonic magician from far away, the Indies, the Sahara, what have you. But she's had milk eyes from the day she was born, our poor Majesty, and only one fellow could have fixed those. The usual reward, of course, would have been half the kingdom, or ennoblement and emolument. But he's a handsome one, our doctor. And ambitious. Why are you looking for him? Did he steal your heart, too?”

She told him.

“Ha! What a mistake to make. It'll be easy to find him. He's caged in the royal palace; you can't miss it. Finest house in the city, and no one can have finer, for fear of beheading. Tallest house in the city, too, by law. She had all the weathervanes sawn off the churches, and would have chopped down the towers, too, except they persuaded her to build her house a little taller. You can see it from here.”

It was indeed the finest house in the city, ringed by green gardens and ponds full of tame swans. Guards bright with old-fashioned weapons marched around its perimeter.

She crumbled a bit of her cake for the swans as she pondered what to do. Then she looked at the wet black legs of the swans.

It was not easy to tear one of her skirts to strips; she had to put her teeth to it. Every four inches she tied a loop, and when she had finished she spread it loosely and broke the rest of the cake over it. As the swans stabbed up the crumbs, she eased the knots shut around their scaly legs. Then she tugged. One of the swans hissed and bit her finger, but the rest, startled, took off in a white cloud. Clinging to their feet for dear life, she rose higher and higher in the air.

Once she was dizzyingly high above the city, she untied the swans one by one, until she held a single blustering cob by the feet. They sank together through the air, landing painfully on the tiles of the palace roof; and then she let him go, as well, and looked about her.

In one corner was a hunchbacked tower, patchy with lichen. To her left and right the castle walls plunged below the eaves. Ilse scrabbled across the slate tiles, kicking one loose — it skittered down the sloping roof and vanished over the edge — and losing a shoe. When she came to the open window she hauled herself up and into a rich bedroom.

A goat-slender man, studying himself in his mirror, whirled around at the noise. She thought she recognized the pointed nose and chin, the glittering eyes.

“Who are you?”

The room was hung with tapestries; the bed was spread with silks and velvets; even the magician's coat glittered thickly with jewels. She was suddenly, painfully aware of the patches on her clothes. But she thought of her sweetheart and mother, and she stood up straight and addressed him.

“Now!” the magician said, after she had finished her story. “I never meant to do that! I cut ice eyes for you because I thought they'd never melt.”

“Will you give them their eyes back?”

“Impossible. Others needed them.”

“What are you going to do?”

“I am going to marry the Queen in a month,” he said. “It's about time I settled down. She's a lovely woman. Proud, though. She won't permit me to work as a petty physician. Must marry a man of leisure, you know. I can't even make you new eyes of rock crystal and glass. Who would restore them?”

“So you are leaving my town blind,” Ilse said. “So you have taken away their eyes, their wedding rings, and their livelihoods, and you'll never return them. You are going to marry a Queen and live, as they say, happily ever after. What a marvelous magician you are!”

He hesitated. “That's putting it rather badly. I could teach you, I suppose. If you are intelligent enough. If you are nimble enough. It might take five years, or ten, depending on how quickly you learn.” He glanced doubtfully at her clothes. “But afterward you could restore sight wherever you wished.”

“Yes,” Ilse said.

“But we must first ask the Queen.”

They found the Queen reading Schiller with her feet propped on a leather ottoman, now and then weeping a decorous tear. She was not a cruel woman. She listened to Ilse's story and sighed, and afterwards gently reproached her betrothed. But their request displeased her.

“Am I to give you up, my love, for ten years so you can train the girl?”

“Hardly — ”

“You may have his instruction,” she said to Ilse, “for one year. I will postpone the wedding for that long, because it is unseemly for a King to teach surgery. But after one year we shall marry, and you will go home.”

Grateful and dismayed, she kissed the Queen's white hand.

And so for a year she studied under the magician, by sunlight, moonlight, and candlelight, paging through abstruse medical texts and reproducing in wet, squiggling lines on blurry paper the elegant anatomical diagrams her teacher marked with a finger. Often she went without sleep and food in her haste to learn.

The magician taught her the structure and composition of the eye, its fine veining, innervation, and musculature; the operation of light and color; sixteen theories of sight from philosopher-doctors in various kingdoms; and common diseases and their remedies. All of this, he said, he had gathered from years of wandering in strange lands among strange people. And when she was exhausted with studying, he told her stories from his travels.

In the flicker of shadows on the wall, her eyes unfocused from much reading, she thought she could see the people he described: the woman who married a tiger, the parrots who kept state secrets, the ship that flew in the air. She fell asleep in her chair with his words still running in her ears, and he dropped a coat over her before he retired, and so they passed many nights.

By the end of the year she could switch the eyes of rabbits, cats, and sparrows without harming them, without even a drop of blood falling on the magician's knives.

“All that I can teach, you know,” he told her one night. “Take my knives, and take this box. I have had time to fashion new eyes for you and yours. Glass and rock crystal, this time.”

She fell on her knees and thanked him.

“But there is one more thing. I know no one as quick and capable as you, or as kind. If you will have me, I will marry you instead of the Queen.”

“That is kind of you, but I have a sweetheart at home,” Ilse said.

“He won't have waited for you.”

“He has. I am certain.”

“Very well,” he said, annoyed. “Go home to him, then.” He was not gracious enough to invite her to the wedding, or even to replace her tattered clothes. So with the box under her arm, and the three silver knives hung at her side, Ilse left the palace.

The soldier at the gate barred her path with his spear. He had a hard face and a rough red beard.

“What are you carrying, girl?”

“Eyes that the Queen's magician gave me.”

“Gave you? You in those rags? Unlikely. An export fee of three gold crowns.” He laughed at her. “Of course you can't pay. But you've a pretty face, and I'll overlook this for a kiss.”

She turned to go.

“Or,” he said thoughtfully, “I could have you arrested and imprisoned. For theft, probably.”

And she saw that he meant it. So she kissed him on his bristly mouth, a sick twist in her stomach, feeling his hands slide up and down her sides, and then he laughed and waved her through.

The road seemed twice as long now. The days grew colder as she went, for it was autumn again, and her clothes were thin, and the road was rising toward the mountains. The crows in the trees croaked and chuckled as she passed.

After many days of weary walking, she saw with great relief the goatherd's village. The sunflowers were brown and rattled in the wind, but the cat still sat on the goatherd's roof, and it stretched and purred at her.

She rapped on the door. The goatherd's daughter opened it slightly. Faint lines were sketched into her forehead. Somewhere in the cottage, a child began to wail.

“What do you want?”

“I left a wool smock and a fur cloak with you. Last year, it was. And there were fourteen pieces of silver in the pocket.”

“I don't know what you are talking about.”

“You fed me and you gave me these clothes to wear. Don't you recognize them? Keep the clothes, if you like, but please give me my mother's silver.”

“We feed paupers all the time. Of course I can't remember each one. But there's no food in the house today. There's no food in all the village.” She shut the door.

Ilse had no choice but to continue. The higher she climbed, the colder it was, and she shivered when she lay down to sleep on the lichen-studded stones. But she kept herself warm remembering her sweetheart's smile and her mother waiting for her in darkness.

At last she heard the faint sound of pianos. Tired though she was, she quickened her pace. Soon she saw woodsmoke in the sky, then chimney pots, then houses.

It was as she remembered it. Only now the notes that rang in the cold air were cheerful, and the people walked as though they could see. Ilse went into her own house and found her mother slicing vegetables.