Lance Robertson & Diane Dietz

Debate stirs over anarchist tactics

Tim Ream: The onetime conservative has evolved into a passionate activist leader.

“These guys are show-stealers”

“He always had a strong mouth”

Arrest was “uplifting experience”

“Big timber beast is just laughing”

Property: Police, businesses say vandalism isn't an acceptable way to express a political opinion.

Tim Ream: The onetime conservative has evolved into a passionate activist leader.

By LANCE ROBERTSON

The Register-Guard

Looking at him now — with his scruffy Che Guevara beard, green bandana and shoulder length hair he sometimes braids — it’s hard to believe that Tim Ream voted for Ronald Reagan.

Twice.

“I bought Into the whole Reagan thing,” Ream says. “1 bought into the whole ‘morning in America' trip."

But that was then.

Today. Ream is a radical environmental activist who wants to tear down multinational corporations, save old growth forests, kill the World Trade Organization and dissolve the United States.

When anarchists took the international stage at the violent protests two weeks ago in Seattle. Ream helped organize protests and set up an “independent" media center. producing a videotape of the demonstrations, police response and melee that ensued when anarchists from Eugene and elsewhere smashed windows and vandalized stores

On the surface. Ream's traditional Midwestern upbringing makes him an unlikely leader of a movement that hopes to bring down the corporate world and advocates private property destruction as a way to achieve political gain. But his life experiences over the past 15 years, from serving in the Peace Corps to his lead role in the famed Warner Creek logging road blockade near Oakridge, shaped his progression from a conservative college kid to a 37-year-old revolutionary.

Ream calls himself an anarchist for want of a better label. “I'm not a communist. I’m not a capitalist. So yeah, I guess I’m an anarchist.” he says.

He is but one example of how antiauthoritarian Eugene — a longtime incubator of protest and free speech — has become home to a nucleus of radical demonstrators.

Business owners, much of the public and even longtime activists may condemn their actions or not understand them, but Ream’s story sheds some light on what draws people to adopt extreme views.

“These guys are show-stealers”

Ream also is an example of how anarchists come in all different stripes.

At one extreme, there are those who think Unabomber Ted Kaczynski is a hero and support violent revolution. But there also are those who hand out free food and clothing to people in the Whiteaker neighborhood, the hub of Eugene’s anarchist movement. Others run an anarchist school or sit in trees in the Willamette National Forest to protest logging plans. They have a radio station and run the “Cascadia Alive” program on public-access television.

The Earth Liberation Front — a shadowy group blamed for several acts of sabotage in the United States since the mid-1990s, including an arson at a Forest Service ranger station east of Salem and the burning of the ski resort at Vail, Colo. — has anarchist ties.

Ideological differences are OK, anarchists say, because that is the essence of anarchy: Each person is free to define it in his or her own way.

"It would be a mistake to write these people off as hooligans and petty vandals,” Eugene environmental activist James Johnston says. “Ninety-eight percent of this crowd are well-spoken and pretty rational. They have an impressive and sophisticated political agenda. They sometimes may look like it, act like it and talk like it, but they aren’t hooligans.”

That view isn’t shared by everyone in Eugene’s activist community.

“I beg to differ with these self-named anarchists,” says Vip Short, a longtime Eugene peace and anti nuclear activist who has participated in several civil disobedience actions at nuclear test sites in Nevada. “Their approach — we’re going to smash things up and then figure out a peaceful world among the ruins — that pretty much sums up their whole philosophy. They just don’t get it.”

Short says that by vandalizing private property, the anarchists are “serving the very forces of repression they claim to oppose. They’re giving more power to their enemy in the long run” by provoking police and creating a backlash against the message they’re trying to convey to the general public.

But in the wake of the WTO melee, even activists who reject anarchy and property destruction concede that the anarchists focused global attention on the World Trade Organization, though in reality the thou sands of people who blocked city streets — not those busting out windows at Starbucks — shut down the WTO.

“Some people feel that if it (the property damage) hadn’t happened, we wouldn’t have gotten so much coverage,” says Lisa Wisnewski, a Eugene activist with the Alliance for Democracy, which took a strict nonviolent stance at the WTO protests.

Although the group rejects the destructive tactics of the anarchists, mainstream

activists recognize that “this would have been a front page story for one day without the window smashing,” Wisnewski says.

Short sees it another way: The anarchists detracted from the peaceful demonstrators’ message.

“These guys are show-stealers,” he says. “There’s nothing that irks a political activist more than to put so much time and effort into a peaceful demonstration and then to have it literally ripped off in a few moments’ time.”

“He always had a strong mouth”

Eugene’s anarchist movement is rooted in the 1995-96 protest over the U.S. Forest Service plan to log timber in the arsonist-burned Warner Creek area east of Oakridge. In September 1995, activists threw up a blockade across Forest Road 2408 near Oakridge, the only way into the timber sale.

They dug trenches across the road, piled up rock barricades and built a log fort, complete with parapet and drawbridge across a deep ditch in the road. Cascadia Free State, they called it.

And there they stayed for 11 months, until federal agents raided it — two weeks after the Clinton administration, bowing to intense public pressure, canceled the logging.

They created a little village, very similar in structure to the kind of locally based community anarchists want for this world. There was a government, so to speak, but it consisted mainly of the group making decisions by consensus.

There was even a form of law enforcement, only without weapons or use of physical force. Two people were expelled from the Warner Creek encampment, one for bringing a weapon into camp.

Tim Ream was in the thick of the Warner Creek fight. His brain power and gift for spitting out short sound bites to reporters made him a natural for the media covering the story. He sported short hair, a winsome smile and a clean-cut image — a sharp contrast to the ragtag-looking crowd camped out at Warner Creek.

“He’s always had a strong mouth,” says his father, James Ream. “I never argue । with the kid on anything, whether it’s politics, abortion, guns. He’s very knowledgeable and articulate on so many subjects, and I’m not likely to change his mind.”

After living at Warner Creek for a few weeks, Ream thrust himself into the spotlight with a hunger strike outside the Federal Building in Eugene to protest old growth logging. He lasted 75 days, gaining national notoriety and earning the respect of forest activists.

He escorted a crew from “60 Minutes” to Warner Creek. He flew to Washington, D.C., to lobby Congress to repeal the law that allowed the continued logging of old growth forests. He went on a whirlwind, 34-city national speaking tour.

Ream’s forest activism, hunger strike and five arrests for protesting government logging policies — including one in which he was dragged by his hair down a hallway at the Lane County Jail — help explain how his philosophy of protest evolved.

“Tim is analogous to the New Left leadership of the '60s ... the same people who became leaders in the Vietnam War protests,” says Tim Ingalsbee, a forest activist who heads a wildfire ecology center in Eugene. “They were America’s best, brightest and most motivated people. Many of them got radicalized at the end of a policeman’s baton. That will change you more than any class you can take in college. Tim reminds me a lot of those folks.”

Peace Corps duty opens eyes

Ream grew up in Aurora, Ill. His father worked for the Social Security Administration and his mother was a high school science teacher.

He played high school football, wrestled, was a Boy Scout and participated in his church youth group. He was always interested in politics and current affairs. He remembers his mom yelling at him for staying up so late to watch one of the political conventions — perhaps the 1968 Republican convention when Richard Nixon was nominated.

“He was always very smart, very inquisitive,” his father says. “I remember taking him to museums when he was little. He would stop and study everything to death. Here we were, trying to move on and he’d linger and linger on.”

Raised a Catholic, Ream went to Jesuit-run Creighton University in Omaha, Neb., majoring in science and psychology, then on to graduate school at Loyola University in Chicago.

Creighton has a strong philosophy of social justice and encourages students to travel abroad and help others in the Third World.

“I was raised to be service-oriented," Ream says. “1 had very idealistic teachers who believed in a world where you had to do good.”

In 1986, Ream joined the Peace Corps and was assigned to teach high school in Lesotho, a kingdom surrounded by South Africa. It was an experience that changed his life dramatically and pushed him toward environmental and social activism. It also helps explain many of his views about the need to dissolve big corporations.

He saw poverty, apartheid in nearby South Africa and the influence of corporations and media conglomerates that controlled the news.

Tom Ostrom, a Peace Corps volunteer who served with Ream in Lesotho, says Ream had a “less is good” viewpoint about government and a favorable attitude about big business when he first arrived in the country.

Ream says he was generally conservative, especially on fiscal issues and foreign affairs. He remembers being horrified when another Peace Corps volunteer played the song, “Free Nelson Mandela,” as they left the United States on a jet to their assigned countries.

“Being a Reagan Republican, I thought, he’s (Mandela) a communist terrorist, and here I am with all these people who support this communist terrorist.” Ream says. “I bought into the whole corporate view of the world, that corporations provide us with free enterprise that makes us the greatest country in the world.”

But that changed fast.

“I didn’t like what I saw”

“Politically, Tim went through a transformation,” says Ostrom, a fisheries biologist now on sabbatical from his job in the Puget Sound area and living in England. “Tim saw the oppressive apartheid regime in South Africa. There was the poverty. His world view slowly changed. He started to understand the role of information and the media in being instruments of repression in authoritarian places.”

Ostrom says Ream would get upset reading newspapers that ignored the oppression in South Africa. And most American media giants either ignored Africa or relegated international news to the back pages, Ostrom added.

“For the first time, I saw my country from the outside, and I didn’t like what I saw,” Ream says. “I had race and class issues articulated to me by people in ways I’d never heard before. I saw how foreign corporations controlled the diamond mines of South Africa. Apartheid no longer was a theory, but an economic tool to exploit labor and take resources away from people.”

Ream also tried to buck the system, Ostrom says. For example, Ream wanted to launch a grass-roots, anti-poverty effort to get food to local villages, but Peace Corps higher-ups wouldn't go for it. Despite orders to halt his program, Ream went ahead with it anyway. It was a project “outside our normal assignment, so he came under a lot of heat from the director,” Ostrom says.

“He’s never shied away from confrontation with authority,” Ostrom says.

Ream also developed a “strong environmental ethic" while in the Peace Corps, says Ostrom, who traveled around Africa with Ream for six months after their tour of duty ended in 1989. They stay in touch only infrequently now.

“I saw the destruction of the African rain forests,” Ream says. “I got a sense of how we could decimate the ecosystem on a worldwide basis.”

When Ream returned to the United States, he went to work right away for the Environmental Protection Agency in New York. His job was to evaluate various environmental cleanup and protection plans developed by the agency. He also taught some internal courses for employees on preventing fraud and waste. In the meantime, he finished work on his master’s degree in psychology, which was awarded by Loyola in 1990.

After 18 months in New York, he transferred to the EPA’s office in North Carolina, where he largely analyzed the effectiveness of air-quality plans.

He also worked with corporations, environmental groups and others on “lifecycle assessments,” which looked at the environmental effects of certain choices people make. The program tried to gain consensus on environmental programs the EPA was responsible for.

“I’d try to answer questions like, paper vs. plastic or cloth vs. disposable diapers,” Ream says.

In late 1993, although he was making nearly $50,000 a year, he soured on government work and quit, setting off a series of events that landed him in Eugene two years later.

“I never thought I was making much of a difference,” he says. “I saw a lot of well-intentioned people work hard on projects that could benefit the Earth, and every step up the management ladder they were twisted and softened so that when they were enacted, they did nothing or the opposite of what they were intended to do.”

Arrest was “uplifting experience”

Ream had begun reading the Earth First Journal, the publication of the radical, loose-knit environmental group that advocates vandalizing such things as logging equipment to keep public forests from being cut.

He also read up on Zen Buddhism, and when an engagement broke up, he drifted West and entered a Buddhist monastery in Northern California.

“I just needed to get away for a while,” he says.

He gave some thought to making the monastic life permanent. But he left after a year, deciding he wanted to get active in environmental and social issues. I realized 1 was much more oriented in the real world,” he says. “I knew my work should be focused on helping people outside the monastery walls.

Ream still occasionally retreats to the monastery. What’s ironic about it is that wake-up times and other rules are rigid inside the monastery, a sharp contrast to the anarchist way of thinking. But he says he finds that the monastic life helps him become “much more clear and positive about the world.”

In late 1994. activists were battling Pacif ic Lumber Co. and the government over the Headwaters forest, the last remaining stand of old gi-owth redwoods in private hands.

He went to a rally outside the California Department of Forestry office, sat down with others and got arrested — the first of five arrests for protesting government logging policies.

“I was conditioned as a kid to be a good boy, obey the law and fear the police and the government,” Ream says. “Getting arrested was an uplifting and empowering experience."

Ream had met some Eugene activists in the redwoods and decided to move to Oregon in 1995. By then, he was knee deep in forest activism. He attended Earth First's Round River Rendezvous in Arcata, Calif,, earlier that year and says he slowly became a believer in “eco-sabotage” practiced by Earth First.

Ream says he chose to keep his views about sabotage to himself, even through the Warner Creek blockade and hunger strike.

“He was very Gandhi-esque”

In fact, it wasn’t until recently that Ream began to openly advocate property destruction as a political tool. He admits that he "has destroyed property” but won’t give details.

In the past, he publicly pushed a more traditional approach to protest: Nonviolent, nondestructive civil disobedience. Block a road, then go limp when the police come to arrest you. Sit in trees, but don’t resist physical force by the police.

In mid-1995, Ream was living in the Cottage Grove area, “couch surfing” with friends and activists so he didn’t have to pay rent. The Warner Creek logging looked imminent, thanks to a legislative rider that Congress attached to a spending bill that allowed the project and others.

Activists had set up a base camp at Warner Creek and prepared for tree sits, blockades or whatever might be necessary to stop the logging.

One day, Ream went to Warner Creek with Ingalsbee, who was fighting the Forest Service over its plans to log trees in the area east of Oakridge that an arsonist burned in 1991. Ingalsbee and Ream took a long walk together up Forest Road 2408, where Ream saw for the first time the area slated for logging.

Ingalsbee says Ream was thinking of going back into the monastery.

“I talked about what a moving experi ence the defense of Warner Creek would be,” Ingalsbee says. “It was a beautiful day, and he could see what was at stake. He was sold on the idea.”

In September 1995, Ream and Ingalsbee were among a number of eventual Warner Creek activists attending a training camp run by the Ruckus Society at Breitenbush, east of Salem, when a court ruling cleared the way for the Warner Creek logging to begin. They immediately drove to Warner Creek and blocked Forest Road 2408.

Johnston, the Eugene environmental activist, remembers Ream’s involvement in the early days of the blockade. He advocated nonviolent civil disobedience and wanted alcohol banned from the encampment.

“He was very much committed to a paci fist, nonviolent code. He was very Gandhi-esque,” Johnston says.

But, like most of the more extreme forest activists at the time, Ream wanted an end to all commercial logging on public lands.

“Big timber beast is just laughing”

Although activists won at Warner Creek — it was the first time an already-sold timber sale had been canceled as the result of direct action — Ream began moving even further toward a philosophy of anarchy that advocates property destruction and the breaking up of the United States into small, locally run communities that govern themselves by consensus.

Ream says he came to the conclusion that forest policy wastft going to change without a different approach. He helped organize many of the tree-sits and protests through the last half of the 1990s against other West Coast timber sales whose names are as familiar to local forest activists as Iwo Jima and Guadalcanal are to the U.S. Marines: Judie, Headwaters, China Left. Growl and Howl and Sugarloaf.

“Although we continued to have some victories, their scope was trivial compared to the defeats,” Ream says. “Forest- byforest victories are great, but it isn t enough. The big timber beast is just laughing. While it didn’t get to take a bite out of Warner Creek, it just turned and took a bite out of the forests somewhere else.”

Ream was convinced that nothing would change as long as big timber companies and other multinational corporations continued to operate and wield influence over politi cians and people. So he figured the best way to solve the problem was to get rid of the corporations.

“We have to go after the root of the problem, and that is the shield of corporate irresponsibility.”

Property destruction, he adds, “is a way to take away their profit” and ultimately force them to dissolve.

But Ream draws the line at destruction of “corporate property,” such as logging equipment and the businesses or offices of multinational companies that exploit workers or harm the environment.

He doesn’t advocate violence against people and rejects damage to “personal” property, such as someone's home, car or small business. He’s disgusted with recent acts of vandalism in the Whiteaker neighborhood, where telephone lines have been cut and windows broken at small businesses there.

“It’s extremely misguided and destructive to our community,” he says.

Ream says private property destruction to achieve political gain is “as old as the American Revolution. ... That was corporate tea that was dumped into Boston Harbor.”

The United States also should give way to small communities or groups within established cities that govern themselves, Ream says.

“Power would rest in the hands of local communities, not big government and big corporations," he says. “It tends toward a very American West kind of anarchy: 1 do what I want to do. In a way, you could say that Ronald Reagan was an anarchist.”

Ingalsbee says Ream’s philosophy is similar to “communitarian anarchy,” the way some of America’s early colonies began.

“There’s a lot of components of anarchy that we just call democracy,” says Ingalsbee, who has taught classes at the University of Oregon on anarchist philosophy. “Individual rights, for example, is an anar chist philosophy.”

Johnston says one reason anarchy is growing in popularity is that “the old tactics of social change aren’t working. You can stand in front of the Federal Building, waving a sign, until the cows come home, and it’s not going to change a dang thing. The logging continues despite overwhelming public opposition. A lot of people are starting to feel that this protest crap just isn’t cutting it anymore, and so we need to go break some windows.”

Ream says the public and media don’t understand that there is a difference between violence and property destruction. Most anarchists are nonviolent, he says, but advocate property destruction against specific targets to achieve a political goal.

But Ream says he’ll use “whatever tool in the toolbox will work.” He admires the thousands of people in Seattle who just sat down and blocked intersections in a more classic form of civil disobedience because it worked.

“Tim’s a doer”

Ream lives in a small, two-bedroom house in the Whiteaker neighborhood, near the replica of Eugene Skinner’s cabin at the park named for the city’s founder. He doesn’t work and says he’s living off savings from his EPA job. Ream thinks it would be great to find a homeless family to live in Skinner’s cabin, since he supposedly opened his door to those in need soon after building it more than 150 years ago.

In one room is the video equipment he and fellow activist and videographer Tim Lewis use to make videos. The kitchen is simple, with avocado-colored appliances. A set of barbells sits in the middle of the tiny, Spartan living room.

Ream doesn't have a television or compact disc player, but an answering machine usually has a half-dozen messages waiting for him whenever he gets home.

He doesn’t own a car and either rides his bike or walks. He bought his kitchen table from a neighbor for $10. His only form of electronic entertainment at home is an AM FM clock radio.

His Peace Corps experience taught him “to live real cheap,” Ream says. A large backyard garden provides food. After returning from Seattle two weeks ago, he harvested a giant Hubbard squash, which took a prominent spot on his kitchen counter as he slowly whittled it away for several meals.

Ream worked with Lewis to produce a video of the Seattle protests. They've distributed or sold for $5 each about 1,500 copies, and “60 Minutes II” relied on some of the footage for a recent broadcast on Eugene’s anarchists.

Ream’s family still lives in Aurora. His parents are divorced. His mother, Carol, visited him in Eugene last year and appeared on the “Cascadia Alive” public-access television show Ream helped start. She says she supports his efforts to save old growth forests.

His dad doesn't approve of his son’s anarchist tendencies, but “as far as the environmental issues he's concerned with, I support what he’s doing.”

Ream still remembers to send a birthday card every year to his grandmother, Rose Ream, who is 87 and also lives in Aurora.

“He’s a wonderful kid,” she says. When Ream comes to visit, she hides all the paper napkins and paper plates because they aren’t reusable.

Ream’s role in the Eugene anarchist scene is one of support rather than leader. And he’s certainly not a “guru” that other anarchists look to for philosophical guidance, like John Zerzan, the Eugene anarchist writer.

Ream moves easily between divergent groups, networking and maintaining relationships with black-clad anarchists as well as mainstream environmental groups such as the Sierra Club and Oregon Natural Resources Council. He refuses to talk about his connections with the anarchists who participated in the June 18 riot or other actions in Eugene.

“There aren’t any real leaders,” says Johnston of Eugene’s anarchist movement. “Tim’s a doer. He’ll sit in the trees or talk to the cameras. He can move a crowd and he commands respect. But there’s no Martin Luther King of this movement. That’s on purpose. There’s more a spirit of individualism.”

Property: Police, businesses say vandalism isn't an acceptable way to express a political opinion.

By DIANE DIETZ

The Register-Guard

A new attitude about property destruction in the Eugene activist community is alarming police, business leaders and some old guard activists

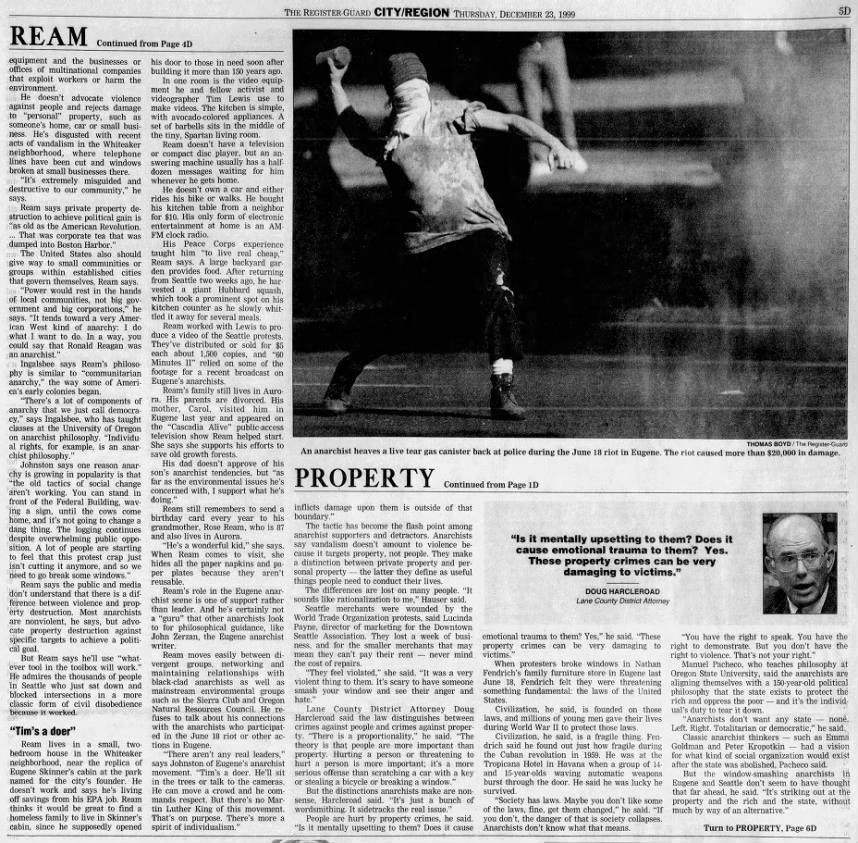

In June In Eugene and November in Seattle, protesters smashed windows, threw rocks or spray painted businesses to make anti government, anti-corporate points.

“The freedom to express your point of view is not without boundaries." said Dave Hauser, president of the Eugene Area Chamber of Commerce. “Any activity that endangers people's lives or inflicts damage upon them is outside of that boundary.”

The tactic has become the flash point among anarchist supporters and detractors. Anarchists say vandalism doesn’t amount to violence because it targets property, not people. They make a distinction between private property and personal property — the latter they define as useful things people need to conduct their lives.

The differences are lost on many people. “It sounds like rationalization to me,” Hauser said.

Seattle merchants were wounded by the World Trade Organization protests, said Lucinda Payne, director of marketing for the Downtown Seattle Association. They lost a week of business, and for the smaller merchants that may mean they can't pay their rent — never mind the cost of repairs.

“They feel violated,” she said. “It was a very violent thing to them. It’s scary to have someone smash your window and see their anger and hate.”

Lane County District Attorney Doug Harcleroad said the law distinguishes between crimes against people and crimes against property. “There is a proportionality,” he said. “The theory is that people are more important than property. Hurting a person or threatening to hurt a person is more important; it’s a more serious offense than scratching a car with a key or stealing a bicycle or breaking a window.”

But the distinctions anarchists make are nonsense, Harcleroad said. “It’s just a bunch of wordsmithing. It sidetracks the real issue.”

People are hurt by property crimes, he said. “Is it mentally upsetting to them? Does it cause emotional trauma to them? Yes,” he said. “These property crimes can be very damaging to victims.”

When protesters broke windows in Nathan Fendrich’s family furniture store in Eugene last June 18, Fendrich felt they were threatening something fundamental: the laws of the United States.

Civilization, he said, is founded on those laws, and millions of young men gave their lives during World War II to protect those laws.

Civilization, he said, is a fragile thing. Fendrich said he found out just how fragile during the Cuban revolution in 1959. He was at the Tropicana Hotel in Havana when a group of 14-and 15-year-olds waving automatic weapons burst through the door. He said he was lucky he survived.

“Society has laws. Maybe you don't like some of the laws, fine, get them changed," he said. “If you don’t, the danger of that is society collapses. Anarchists don’t know what that means.

“You have the right to speak. You have the right to demonstrate. But you don't have the right to violence. That’s not your right.”

Manuel Pacheco, who teaches philosophy at Oregon State University, said the anarchists are aligning themselves with a 150-year-old political philosophy that the state exists to protect the rich and oppress the poor — and it’s the individual’s duty to tear it down.

“Anarchists don’t want any state — none. Left. Right. Totalitarian or democratic,” he said.

Classic anarchist thinkers — such as Emma Goldman and Peter Kropotkin — had a vision for what kind of social organization would exist after the state was abolished. Pacheco said.

But the window-smashing anarchists in Eugene and Seattle don’t seem to have thought that far ahead, he said. “It’s striking out at the property and the rich and the state, without much by way of an alternative.”

But Michael Dreiling, a sociology professor at the University of Oregon, said the young anarchists he has talked with are thinking about alternative social structures.

"The young people we’re seeing involved in this — whether from Seattle or Eugene — they have a very sophisticated understanding of the world," he said.

Neil Van Steenbergen, a human rights activist, tried to keep the peace during the June 18 riot.

He placed himself between anarchists and a motorist who had angered them.

“Anything that violates the rights and dignity and property of anyone else is violence,” he said. “If somebody breaks a window, for me, that’s violence.”

But Van Steenbergen also considers certain corporate practices to be violent, including "working conditions that would not respect the dignity of the workers, that would not provide decent living standards, where women would be pressured to give in to sexual advances, where children would be exploited.”

Steenbergen and others in the Eugene activist community, however, say there are other, more powerful ways to make a point, such as nonviolent demonstrations, passive resistance and exercising individual spend ing power to favor only companies that respect workers and the environment.

Gillette Hall, chairman of the Eugene Human Rights Commission, said violent acts, such as breaking windows, breeds violence.

“It’s a very risky slippery slope trying to parse out what kind of violence is acceptable,” said Hall, who stressed that she was speaking for herself, not the commission. “Frankly, I find that ridiculous and counterproductive. We’re all part of a community. When one member of the community breaks the fiber of trust, that is a destructive act.”

But Ron Chase, also a member of the human rights commission, said a lot of people share the anarchists’ frustration.

ANARCHY’S TOLL

-

Seattle, Nov. 29-Dec. 3: $2.5 million to repair windows and graffiti and $17 million in lost sales during riots.

-

Eugene, June 18: $20,691 in damages to businesses and police cars.

—Eugene Police Department and the Downtown Seattle Association

“If you want to talk violence against windows, how about violence against children who get forced into labor?” said Chase, who also was speaking for himself. “If that’s the only way (anarchists) can be heard, and they are willing to accept the consequences, so be it.”

In the weeks after the Seattle protest, some longtime Eugene activists have been reluctant to condemn the anarchists. In Seattle, Peg Morton said she was bothered by the destruction and wanted to help clean it up.

“When you destroy, you are hurting your own humanness. You’re undermining your own humanness,” she said.

But, now, she said she's listening to — not condemning — local anarchists.

She chooses to focus on the subject of their actions: repressive practices by corporations, which are allowed or supported by governments, including the United States, she said

“The violence done by the World Trade Organization,” she said, “creating starvation and poverty and violent repression in the developing world is infinitely more important than breaking windows.”

Eugene activist Charles Gray, who participated in nonviolent protest in Seattle, said the argument for or against property damage is nothing new. Similar discussions went on between the followers of Martin Luther King Jr. and the Black Panthers in the 1960s.

The discussion is particularly heated in a capitalist country, where the laws and many people’s values center on property rights, and that’s not necessarily good for human beings, in Gray’s view.

“In my mind, there certainly is a sharp distinction between harming human beings and harming property,” Gray said. “But in our culture we have sanctified property. Somehow property is sacred, and it can’t be touched.”

Vip Short, a founding member of Eugene Peaceworks, said the window-smashing protesters are making a false distinction. They contend that corporations are nameless and faceless, he said, but that’s not true. Human beings are always there.

“I am very disturbed by this notion emanating out of corners of Eugene. It’s basically and end-justifies- the-means distinction,” he said. “It’s an extremely thin pretext.”

Downtown Eugene business owners don’t even want to talk about anarchists.

They say they’re afraid that expressing their views will make their businesses the target of anti-corporate activity.

“It’s probably easier not to say anything,” said Hauser, the chamber president.

“It’s a bit ironic, isn’t it?”

Several activist, political groups call Eugene home

Eugene is a home to all kinds of political activism. Thirty-year-old anti-nuclear and anti-war groups are turning their attention to human rights and trade issues and finding new vigor.

In two years, a half-dozen new activist groups have emerged locally. Most are dedicated to nonviolent activism; a few are willing to damage other people’s property to make a political point.

Here’s how Eugene’s activist groups describe themselves and their activities:

Alliance for Democracy:

Age: 1% years

Membership: 60

Goals: To educate the community about globalization and related issues; to mobilize against threats to the environment, workers and democracy. Applying to incorporate as a nonprofit group.

Tactics: Members participated in nonviolent civil disobedience on Nov. 30 in Seattle.

Anarchist Action Collective

Age: 1 year

Membership: A group of writers, publishers and public speakers who distribute literature and coordinate events, including the co-sponsorship of last year’s Northwest Anarchist Conference. Anarchist author John Zerzan is a prominent member.

Goals: To present a radical perspective.

Tactics: Publishes a catalog of anarchist literature.

Anti-Authoritarians Anonymous:

Age: 20 years

Membership: a handful

Goals: To alter corporate logos and other advertising images to make a point. Submits its work to “Anarchy” and “Green Anarchist” magazines.

Tactics: Called “culture jam-ming," the group uses irony to promote anarchist viewpoints. Also known to skewer some of Eugene’s pacifist activists.

Black Army Faction

Age: 1% years

Membership: unknown

Goals: Has advocated violence in posters.

Tactics: A shadowy group that has made militant threats and violent claims. A hooded representative appeared on the "Cascadia Alive” cable talk show and read a statement in favor of breaking windows. Anarchist author John Zerzan said the group is no longer active.

Cafe Anarchista

Age: 3 years

Membership: a handful

Goals: Serves coffee and rolls to homeless people and other neighbors on the streets in the Whiteaker neighborhood. A low-key, informal service.

Cascadia Forest Defenders

Age: 4 years

Membership: hundreds

Goal: Formed when a group of forest activists split from the local chapter of Earth First to disassociate themselves from Earth First’s negative image, but members share the goal of protecting wild places.

Tactics: Tree sitting, road blockades, school presentations, slide shows, distributing fliers at community events.

Cascadia Wildlands Project

Age: 3 years

Membership: about 24

Goals: Works on public lands issues, mostly in the Cascade Mountains. Tries to educate, organize and agitate for better land management.

Tactics: A registered nonprofit organization that works within the bureaucratic and legal structures. Does not advocate illegal activities.

Community Alliance of Lane County

Age: 26

Membership: 1,200 on the newsletter list

Goals: Started in opposition to the Vietnam War. Now works in three areas: Communities Against Hate, researching and monitoring white supremacy; Youth for Justice, a youth leadership development project; Immigrant Rights, which challenges human rights abuses.

Tactics: Conducts forums, organizes rallies, presses government officials. In September, staged a march against skinhead activities in south Eugene. The march included the Eugene mayor and chief of police — and the Lane County district attorney.

Citizens for Public Accountability

Age: 4% years

Membership: 200 active

Goals: Making sure that governments and corporations are accountable to the public for decisions that affect the public. Started in opposition to government handling of Hyundai. Pushed for the Toxics Right to Know law in Eugene. In the future, will look at the extinction of salmon.

Tactics: Holds weekly public meetings, discusses and prioritizes issues. Testifies at public hearings, meets with government staff, interviews political candidates, informs public members via an e-mail network.

Citizens In Solidarity with Central American People

Age: 17 years

Membership: 500

Goals: To educate the community about the economic and political realities in Central America, Mexico, Cuba.

Tactics: Educational events, bringing speakers to Eugene, lobbying elected officials. Also, protests and petitioning. No policy on the form a protest might take.

Eugene Springfield Solidarity Network

Age: 11 years

Membership: 360, including labor, religious and community members.

Goals: Affiliated with the national Jobs with Justice Coalition. Raises concerns of worker rights and economic justice as communitywide issues.

Tactics: Union organizing drives involving religious and other community groups. Sent a busload to Seattle to march in protest of World Trade Organization policies. No official position on civil disobedience; but, in practice, members engage in nonviolent civil disobedience.

Eugene Peaceworks

Age: 20 years

Membership: 400

Goals: Started as an anti-war and anti-nuclear group, but now concerned with peace and justice issues — from capital punishment to food irradiation. Activities include helping to establish Eugene as a Nuclear Free Zone, encouraging the Eugene City Council to pass a Toxics Right to Know law and helping to train more than 100 participants in nonviolent direct action to shut down the WTO conference in Seattle.

Tactics: Founded on the idea of nonviolent protest.

Food Not Bombs

Age: 4 years

Membership: dozens of people take turns collecting food and preparing meals, which are served four days a week in Washington-Jefferson Park.

Goals: To serve healthy vegan meals for free. Members believe food shouldn’t be sold commercially and should never be denied to anyone because they lack money. Gets food from gardens and garbage containers.

Future Political Prisoners of America

Age: 1 year

Membership: 6 to 200, depending on the activity

Goals: To highlight the erosion of human rights and emphasize how people involved in protest become the targets of police. Working for the release of Robert Thaxton, who was sent to prison for throwing a rock at a police officer during the June 18 riot in Eugene. Also, works to free Mumia Abu-Jamal, who is on death row in Philadelphia.

Tactics: Puts on the Subversive Pillow Theater, which shows radical videos on Sunday nights at the Grower’s Market in downtown Eugene. Organized a fall rally against police brutality.

Homeless Action Coalition

Age: 11 years

Membership: 200 members, including former mayors, church activists, homeless people, former homeless people, agency workers.

Goals: Uses the political system and the courts to protect the right of homeless people to vote, sleep legally and be free of harassment or discrimination. Works toward low-income housing.

Tactics: Will use nonviolent protest as necessary. Had plans to occupy City Hall when protesting the city’s no-camping ordinance, but the protest was unnecessary because the city modified the ban.

Human Rights Alliance

Age: 1% years

Membership: 20 students

Goals: Dedicated to anti-sweatshop issues. In the fall, staged a fashion show in front of the University of Oregon administration building to dramatize inhumane treatment of workers in the garment industry. Encourages university officials to adopt a licensing code of conduct for the manufacturers of UO products. Long term, the group hopes to educate people on general global human rights issues.

Tactics: Committee work within the university. Members attended the WTO in Seattle, some marched and some participated in nonviolent protest. Members support nonviolent tactics, but they don’t condemn property destruction.

Network for Immigrant Justice:

Age: 5 years

Membership: a network of eight organizations

Goals: Guards against antiimmigrant legislation, works against abuses of the federal Immigration and Naturalization Service, educates to dispel anti-immigrant stereotypes.

Tactics: Conducts workshops, lobbies or pressures politicians and rallies in support of immigrant rights. No formal pledge, but operates on an assumption of nonviolence.

Red Cloud Thunder

Age: 114 years

Membership: hundreds

Goals: A highly decentralized group that usually holds no meetings and doesn’t publicly articulate its goals, but the fluid membership participates in actions to protect trees at Fall and Winberry creeks in the Willamette National Forest.

Tactics: Tree sitting and wrecking forest roads.

Southern Willamette Earth First

Age: 13 years

Membership: 50

Goals: An offshoot of the Cathedral Forest Action Group, which was active in the early 1980s. Its mission is to take direct action in defense of wild places.

Tactics: Meets weekly to educate people to discuss local issues, and otherwise supplies and supports the Red Cloud Thunder tree-sitters. Also helps with the publication of the national Earth First Journal, which is produced and printed in Eugene. Provides individual members with information about radical tactics, including property damage.

Survival Center

Age: about 30 years

Membership: hundreds

Goals: Umbrella group for university-based social issues organizations, including Forest Action, Human Rights Alliance, Amnesty International.

Tactics: varied

Third Friday of the Month

Age: 6 months

Membership: hundreds

Goals: Formed after the June 18 protest/riot in Eugene to confront the ideas of global capitalism.

Tactics: Stages themed activities. In December, it was a rally of the “Eugene Anarchists for Torrey,” a tongue-in-cheek endorsement for Eugene’s incumbent mayor.