Unpredictable

Why do People Love this Serial Killer?

Between 1978 and 1995, Ted Kaczynski sent 16 bombs in the mail, killing three. So why do people today love him?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CM4kZ3mCvQI

Introduction

In 1942, Theodore or Ted Kaczynski was born in a Chicago hospital, the first son to his mother, Wanda. who’d grown up in a relatively poor immigrant family from Southern Ohio, and his father, Theodore, described as a blue collar intellectual who’d spent the better part of his life selling sausages.

As a baby, his mother later described Ted as happy and normal until around a year after his birth, when Ted had developed hives and rashes on his stomach and needed to be isolated in hospital. It’s said that after this week-long experience in hospital, Ted had become “a dead lump emotionally”,[1] and wouldn’t respond to anyone in any way. Eventually, Ted would of course return to normal, but Ted’s mother had later said that this experience had shaped Ted’s hatred for his mother as well as a fear of abandonment by his parents.[2] Ted himself, though, says the opposite, while he doesn’t deny that this experience affected him at all, he later said that “...as I look back on it now, I don’t think I was any more anxious about being left alone than the average kid of my age.”[3] He’d also said that “[After thirteen years old], my parents never again mentioned my supposed fear of being “abandoned” by them—until many years later, when my mother resuscitated the myth of ‘that hospital experience’ in exaggerated and melodramatic form.”[4]

But as we’ll see in later years, this was only the first of many events that would later influence his life.

Early Start (1943-1958)

During his early years living in the heart of Chicago, Ted had described himself as shy but still able to make friends and socialize in his neighborhood and elementary school. However, because the kids on his block had been, quote, “turning to delinquency”, he’d decided to take a step back and spend more time alone.[5]

At around seven years old, Ted’s parents would have his baby brother, David Kaczynski, before moving to Evergreen Park, where, his parents hoped, Ted would have better friends to play with.

But this is when the first big turning point in Ted’s personality would happen. After transferring to a new school, a guidance counselor recommended that Ted skip a grade because of his advanced understanding of various subjects and high IQ. And so, Ted skipped Grade 6, going directly into Grade 7, a decision, he says, “was a disaster for [him]”.[6] Now with kids a year older, he struggled to be accepted by them, and was often subjected to insults by, who he described as, the “dominant” or “tough” kids.[7] Along with this, Ted recalls that, after having his little brother, his mother’s personality had become more pessimistic and verbally abusive. So, along with the kids from school, he says his parents would, “have frequent outbursts of rage during which her face would become contorted and she would wave her clenched fists while unleashing a stream of unrestrained verbal abuse.”[8] Because of these things, Ted spent more and more time alone, and quickly became bored with his friends and with school.

Later, Ted would again skip a grade, and go straight into senior year. At this point, Ted had become resentful towards his parents and his guidance counselors for creating the pressure of getting good grades. “I took no pride in my grades and resented the school. So a couple of times I did cheat on exams. I never felt ashamed of this.”[9]

With a good academic record and advanced understanding of subjects, especially math, Ted was encouraged to apply to Harvard. As a part of the application, he was required to write an autobiographical essay, where he describes himself as unsocial and someone who keeps to himself,[10] character traits that would later shape his time at Harvard.

System failure (1958-1972)

So, at 16, Ted graduated high school and started university at Harvard. Ted later said that he wasn’t particularly excited about going as the pressure and tension was starting to get to him, in part because of the social aspect, but also because he was going to be living alone at 16 years old. Ted, more now than ever, felt completely isolated. “The statement that I isolated myself from my classmates is not quite correct. It would be more accurate to say that my classmates isolated me. They never invited me to go anywhere with them or do anything with them, they never invited me to their rooms, they showed little or no interest in having conversations with me ... I did at first try to make friends with them, but they appeared unresponsive...”[11]

In his second year at Harvard, Ted was convinced, against his better judgment, to join a psychological study that measured how people reacted under stress. Students who joined the study were told to write an essay detailing their personal values and ideology,[12] which would then be used to interrogate and attack the students. It was described as “sweeping, and personally abusive”.[13] Unbeknownst to the students, who were told the experiment would be one year long, it took place over three academic years, and it was said that Ted had spent 200 hours in the study. Was this when Ted’s distrust in science and technology formed? Ted says that while he despised the experiment and the people involved, it had no significant effect on his life.[14]

It’s impossible to say what exactly sparked Ted’s “anti-tech” ideology but it’s likely that, during his Harvard years, a mix of personal issues along with his critique of society, was enough for him to put together a theory to explain his anger and isolation. On one hand, he was becoming more and more distant from his family and began to resent them, as previously mentioned, Ted felt his mother had become verbally abusive and he’d been pressured to achieve at Harvard and in clubs. Socially, Ted wasn’t much better, feeling more and more isolated from the other students. One thing that especially bothered Ted was the amount of “snobbery”,[15] as he called it, at Harvard. On the other hand, as Ted became increasingly immersed in Harvard readings and courses, he started to believe that technology and science were destroying nature and people’s individual freedom, and Harvard was contributing to it.[16]

By the end of his years at Harvard, Ted was offered a student-teaching position at the University of Michigan, where he decided he’d pursue a postgraduate education. While at Michigan, Ted was becoming increasingly dissatisfied with math, pure math was more of a game to him, nothing to make a career out of, but he says, “If I quit my mathematical career, I could expect to get drafted.”[17] The Vietnam war had been going for years at that point but becoming a soldier to Ted, was becoming just another gear in the system, as he says, “I would never become a docile and willing slave to the machine.”[18]

Ted had begun to feel an immense hopelessness in his life and career, but it all changed when he says, “Because the future looked utterly empty to me, I felt I wouldn’t care if I died. And so I said to myself, ‘why not really kill [my] psychiatrist... or anyone else whom I hate.’”[19]

Ted had had the idea of living in the wilderness for a while now, and this was the perfect excuse, he says his plan was to detach himself completely from society, kill someone he hated, and then evade capture for long enough to kill again.[20] He took an assistant teaching job at the University of California Berkeley to save up enough money to execute his plan.

A foothold for revolution (1972-1987)

By 1972, Ted had built a cabin in the wilderness just outside of Lincoln, Montana, he didn’t have electricity or running water and would occasionally ride his bike into Lincoln to visit the library and supplement the food he grew. “Often, when I was alone in the woods and for a long time. my anger would fade away, and I would have a good feeling toward the human race - but only until I was awakened at night by a sonic boom, or disturbed by the sound of a motorcycle tearing up the mountain meadows, or reminded of the fact that my health might be dependent on the judgment of the jerks responsible for maintaining storage facilities for atomic waste.”[21]

As time went on, Ted witnessed how civilization had affected the wilderness around him, and by 1975, he’d started to set small traps in his surroundings, stretching a wire on a motorcycle trail at neck height, vandalizing other people’s camps, smashing windows, and popping people’s tires.[22] But these traps started escalating, “my happiness in my Montana hills is spoiled every time an airplane passes over or anything else happens that reminds me of the inescapability of civilization. There was just one thing that really made me determined. and that was the desire for revenge. I wanted to kill some people, preferably including at least one scientist, businessman, or other bigshot.”[23]

And so, his bombing campaign started. In 1978, Ted had made a makeshift bomb inside of a box that was designed to detonate after opening. After finding the name of an electrical engineering professor at Northwestern University, he addressed the package to him. But after going to downtown Chicago to mail the bomb, he realized it didn’t fit in any of the mailboxes, because of this, he left it in a parking lot near another university, hoping a student or professor would pick it up and be injured.[24] The next day, someone had found the package and delivered it to the professor who it was addressed to, but, obviously suspicious, the professor had called campus security, at which point an officer opened the package, and the bomb was detonated. The officer only sustained minor injuries and the incident wasn’t really reported on. Ted himself wrote, “I checked the newspapers carefully afterward but could get no information about the outcome of what I did - the papers seem to report only crimes of special importance.”[25] So, Ted got to work again.

The next year in 1979, he’d again traveled to Northwestern University and left a bomb disguised in a cigar box. That afternoon, a graduate had opened it and the resulting explosion caused cuts and burns, but again, no serious injury. This one, however, was enough to be put in that day’s newspaper at the Chicago Tribune,[26] and upon reading, Ted writes, “Well, at least I put him in the hospital, which is better than nothing. But not enough to satisfy me^ I wish I knew how to get hold of some dynamite.”[27]

Later that year, Ted set his sight on a higher risk target, this time, an airplane. Equipped with a barometer, Ted says his bomb was set to detonate at 2000ft, but only partially detonated at 34,500ft before smoke filled the cabin and the plane made an emergency landing.[28] Nobody was injured, but because of the safety concern, the FBI had started an investigation. A task force including the ATF and U.S. Postal Inspection Service was formed and named UNABOM, code-name for UNiversity and Airline BOMbing.[29] The FBI noted that the bombs had a sort-of junkyard appearance to them, made by someone who was no doubt clever, but still figuring it out as they go.

Again, a year later, Ted had mailed a bomb in a hollowed out book to the then president of United Airlines. He was hospitalized for severe cuts and burns, but didn’t die.[30] At this point, Ted had begun leaving false clues in his bombs,[31] he would carve the initials FC into various metal components and leave bits of bark or twigs in the bombs.

Over the next few years, Ted would continue mailing and placing bombs at various universities and airline locations, each new bomb being more powerful than the last. The FBI, during this time, had little to no forensic clues as to who this bomber, now dubbed the Unabomber, was. They knew that the bombs were homemade, with materials you could get almost anywhere and they’d theorized that the Unabomber may have an interest in wood, as wood seemed to be the theme for a lot of his bombs.[32]

In the four years between 1981 to 1985, Ted had sent seven bombs, most of which severely injured the recipient, but two of which had been defused.

But, at the end of 1985, things would change. Ted had gone to California to place a bomb behind a computer store in Sacramento, disguising it as a scrap of lumber. This time, however, upon picking it up, the bomb detonated and the owner of the store was killed. The Unabomber had taken his first life.[33] The FBI originally thought that, because the areas being bombed were mostly universities, their suspect should be around university age, and so they narrowed down their search to people born after 1955. Ted was born in 1942.

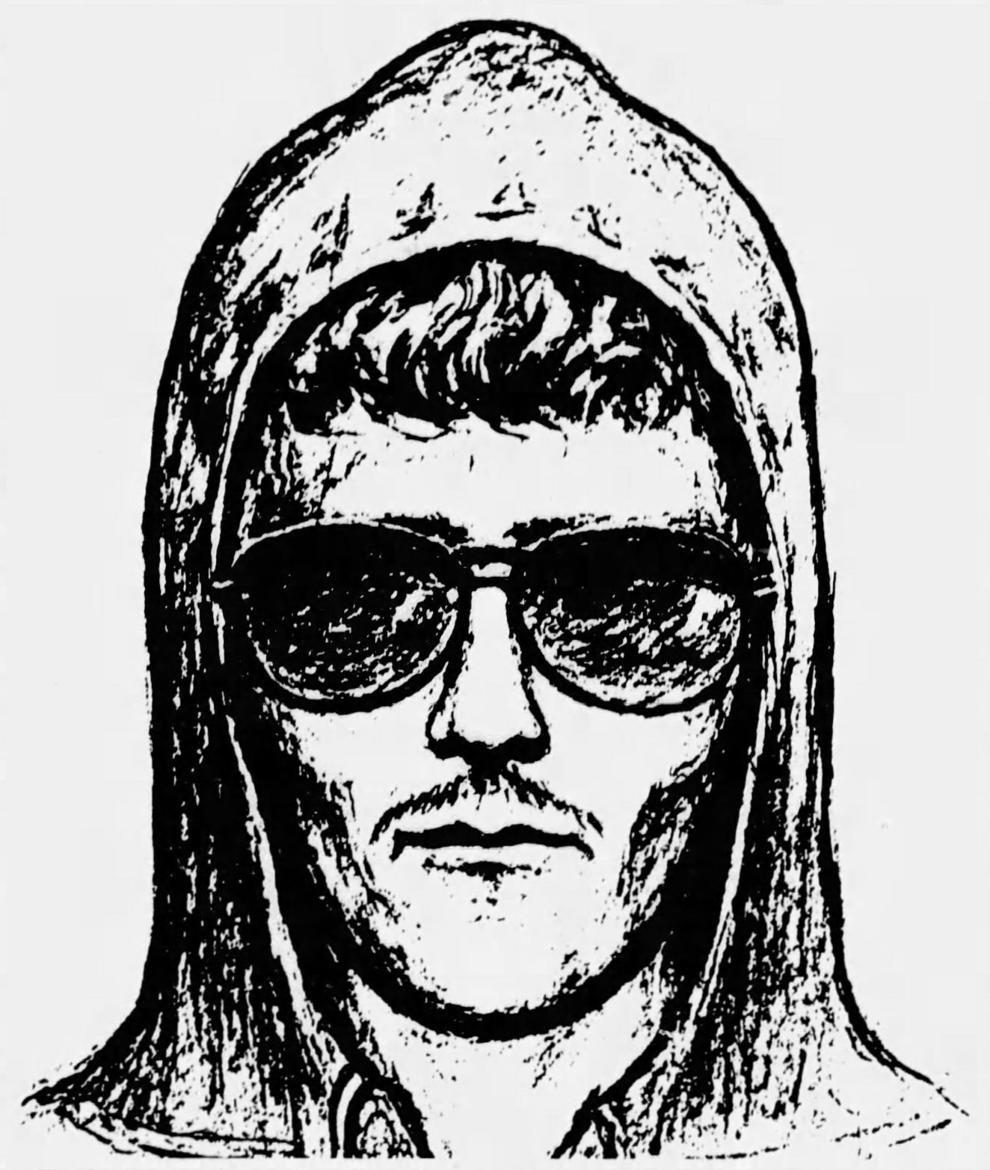

But that didn’t mean all hope was lost. Because two years later, while dropping off another bomb behind a computer rental store and severely injuring the owner, two witnesses had later said they’d seen the man who dropped off the bomb, they recalled a hoodie, aviator sunglasses, and facial hair, and so, the infamous Unabomber sketch was made. Finally, the FBI task force had something to go off of.

Public enemy #1 (1987-1995)

At the same time, Ted had begun getting confident. He’d decided to send a letter to the San Francisco Examiner, claiming that the bombs were the work of a terrorist group named the Freedom Club, remember, Ted had stamped the initials FC on previous bombs.[34] The FBI later confirmed that he was working alone, so this mention of a group of people is probably another deliberate red herring. To prove he was the real person, Ted gave details from his bombs that only he and the FBI would know[35] and, at the end of the letter, he explained his motives. Without wasting too much time, it was written that the group wanted the permanent destruction of modern industrial society, that means things like airplanes, radios, and paved roads.[36] They say that if a small elite of leaders and experts were to control society as they do now, even if their motives were unselfish, “they would still HAVE TO exploit and manipulate us simply to keep the system running”.[37]

This letter was not published by the Examiner, in fact, they later denied receiving any such letter at all.[38][39]

After this, Ted had taken a six year long break, during which the bombings faded from public attention and the FBI was nowhere close to discovering who the Unabomber was.

But Ted had come back hard. In one weekend in 1993, Ted had mailed two bombs, one to a geneticist, Charles Epstein and the other to an accomplished computer scientist, David Gelernter. Upon detonation, the first package had broken Epstein’s arm, and blown off three of his fingers. The second had rendered David’s right hand useless, also causing him to lose sight in one eye, and hearing in one ear. Ted was more thoughtful about David though, writing, “[David] is no cliche, but a highly intelligent, thoughtful, talented, and sensitive man... I consider that he deserved what he got, but that is a judgment that I do not adopt lightly and it is one about which I have mixed feelings”.[40]

Around the time that the Unabomber was active, the idea of radical environmentalism wasn’t new. Groups and organizations had already expressed this notion. One group in particular, “Earth First!” was an advocacy group, focused on action rather than protesting but because of the aggressive nature of their activities, some had drawn a link between them and the Unabomber.[41] At the time, while it was true that some Earth Firsters had grown fond of the Unabomber, and Ted had grown fond of the group, he thought of the group as more reformist than revolutionary. In a letter he wrote to the group, he suggested that they focus less on protecting small plots of land, and more on wreaking havoc on the industrial system.[42]

The last two bombs, mailed in 1994 and 1995, were his most powerful yet. The first targeted an ad executive, Thomas Mosser, who’d helped Exxon repair their image after their oil spill five years earlier. His wife and his two daughters had been having a pretend tea party in the room beside Mosser when he was killed by the package. He was found by his wife, deceased on their kitchen floor. Officers who were on the scene that day had said that it was “particularly devastating”.[43]

The last bomb Ted would mail, was to Gilbert Murray, the President of a timber industry group in California. He’d opened the package and died in his office near the state’s capital.[44]

This death would mark the end of the Unabomber’s bombing campaign but Ted didn’t stop there.

The Infamous Unabomber (1995-Present)

In April of the same year, he would send a batch of letters to various newspapers. In it, he says that he has a long article, between 29 and 37,000 words that he wants published. “If you can get it published according to our requirements, we will permanently desist from terrorist activities... The article will not explicitly advocate violence. nor will it propose the overthrow of the United States Government, nor will it contain obscenity.” The letter goes on to state that the article must be printed in its entirety, no attempt should be made to arrest the group, and while the group will desist from terrorism, they reserve the right to sabotage.[45]

The other letters had been sent to individuals, mostly saying that it would be in their best interest to stop their research in their respective fields.[46][47]

So, after around a month, Ted had left his cabin in Lincoln and mailed three copies of his manifesto to the New York Times, Washington Post, and Penthouse.[48][49][50] But in the midst of this, Ted had also sent a letter to the San Francisco Examiner, saying that he’d blow up an airplane sometime in the next week.[51] As a result, airport security was stepped up throughout the state, and the FAA directed airlines not to accept any mail flown in or out of California, grounding nearly 400,000 packages a day. But a bomb was never found in any of the packages or detonated, in another letter later sent to the New York Times, the Unabomber wrote, “Since the public has a short memory, we decided to play one last prank to remind them who we are. But, no, we haven’t tried to plant a bomb on an airline (recently)”.[52]

After sending letters back and forth with multiple publications, and after around 3 months of careful consideration about the pros and cons of publishing the manifesto, the Washington Post included it in their September 19th newspaper.[53]

It starts off with the now infamous line “The Industrial Revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race”. He writes that the industrial-technological system has had severe damage on the natural world and led to widespread psychological suffering, even inflicting physical suffering for people in third world countries. If it continues, it will reduce humans to “engineered products and mere cogs in the social machine”. So, Ted’s solution is not to overthrow the government, but to destabilize the technological and economic aspect of society.

His first point is a critique of modern leftism, he says that leftists as a community, have feelings of inferiority and are hypersensitive, among other things. He gives the example that leftists have attached negative connotations to harmless words like “chick”, “oriental”, or “handicapped”, and the people who are the most sensitive to those words usually don’t even belong to the group they are supposed to offend. He also writes that most leftists want to conform to society’s expectations even though they appear to rebel against them. He uses the example of the white leftist advocating for black people to be pushed into higher profile jobs, like scientists and executives. He says that this is an example of the white leftist wanting to make the black man “conform to white middle-class ideals”. Quote, “...however much he may deny it, the oversocialized leftist wants to integrate the black man into the system and make him adopt its values”.

Critics of the manifesto question why the Unabomber went this in depth talking about leftists when, later he refers to society as a whole. In the end, while it’s not completely detached, it has little to do with his main point, and some say it seems like he’s just venting.[54]

He then writes about what he calls, “surrogate activities”. He says that because the modern man doesn’t need to spend a whole lot of effort satisfying his basic physical goals, he makes up “artificial” goals to keep himself busy. This includes things like scientific work, athletic achievement, and sports. Because of this disruption of the “power process”, the process of putting in effort to achieve a goal, some have tried to satisfy this “power process” vicariously through other things. He uses the example of Americans satisfying their power process vicariously through their country’s army, corporations, and politics.

He then goes on to critique the motives of scientists, usually scientists justify their research by saying that they wanted to “benefit humanity” but Ted disagrees, saying that some fields do not benefit humanity in any way, like most archeology or linguistics. He claims that, more often than not, scientists do research to satisfy their own power processes, and so, “science marches on blindly, without regard to the real welfare of the human race”.

One of his big points is about individual freedom, or the lack of it. He describes his point best in a journal he wrote a couple years prior: “Consider all the evils that are imposed. by the system. To mention a few: air and water pollution; the threat of atomic war; overcrowding, etc. The individual living independently can at least reasonably attempt to alleviate his hardships. If he is cold he can make a fire. ... If game gets scarce he can try, at least, to find an area where it is more plentiful. His decisions count; he is not helpless. But what can the individual do about air pollution or overpopulation? ... The point I am trying to make here is that the important things in an individual’s life are mainly under the control of large organizations; the individual is helpless to influence them.”[55] He says that the individual can make their own decisions, as long as these decisions are unimportant to the system, like where they choose to live, what clothes they buy, and what job they get.

To much of the public’s surprise, the Unabomber’s manifesto was not only coherent, but somewhat agreeable. Of course, reception was mixed, some saying that the manifesto was “well researched and fairly focused”,[56] others that his bombings hindered his message, and the rest claiming that he needs to be in jail.

Carl Rowan: So that’s a news factor. Secondly when you have the F.B.I. go 17 years, through three deaths and 23 woundings without getting any clues as to who this guy is. I believe that somewhere in this long track. There were some passages that someone would see. And say I know I heard this before and I think I know who this guy is. …

Jane Kirtley: The other thing that troubles me about this whole enterprise is the notion that somehow by publishing this. Days to newspapers feel that they are advancing the cause of Public Safety that they’re basically guaranteeing the Unabomber won’t strike again. I think that’s a tremendous trap for news organizations to fall into. They don’t know who this guy is. They can’t sue him for breach of contract if he bombs again. And they really made a pact with the devil. When they have no …

—Unabomber Manifesto: Publish or Perish? (Video & Transcript)

Speaking of jail, this manifesto seemed to be the FBI’s big break, as they were hoping someone would recognize the writing as a past professor, student, or relative.

The FBI did pick things up from the manifesto though, the Unabomber had used words like “broad”, or “chick”, meaning he was probably older than authorities had originally thought. It also seemed to confirm the fact that the Unabomber had grown up in Chicago, as sources say that some terminology used was indicative of newspapers in Chicago in the 1950s.

But, from all the buzz about the bomber’s manifesto and the abundance of tips that the FBI task force was getting, one man would recognize the writing that would eventually lead to Ted’s arrest. David Kazcynski, Ted’s brother. In fact, David’s wife had had the suspicion that the Unabomber was Ted for a while now, but David, convinced that it wasn’t, usually brushed the thought off. Reluctant at first, David would send a copy of what seemed to be the manifesto’s rough draft,[57] to the FBI and said that the person who wrote it was his brother, Ted. Upon reading it, they were almost certain that the two works had been written by the same person.

And so, on April 3, 1996, 17 years after his bombing campaign had started, Ted Kaczynski was arrested at his cabin in Montana. During his trial later that year, he was sentenced to eight life sentences, avoiding the death penalty.

News Reporter: Federal agents have taken into custody a man may suspect as the Unabomber. This drama is unfolding outside the tiny town of Lincoln, Mt, and Tom Foreman is there.

Local Resident: He was just a real quiet guy, you know? He came to town, he never bothered anybody. He never gave anybody a hard time. He was never in trouble. Never was at the bars. Just a real. Quiet guy and you know, if you had a conversation, it was a real intelligent conversation with him. Know he’s just. Just not the guy that I would think would be the Unabomber.

—ABC News Footage on Ted Kaczynski’s Arrest. (Video & Transcript)

What’s interesting though, is even decades after Ted’s arrest, the public, especially younger people, still agree with his work, saying that it’s more relevant now than ever. It’s safe to say that most people fear the implications that widespread technology has on humans, or what technological advancements will mean for society.

A lot of young people seem to relate to the anti-tech sentiment expressed in the manifesto, “...and its deleterious effects on society. Surrounded by screens from early childhood, addicted to near-constant media consumption, often lacking basic in-person social skills, many sense a broader problem in their own individual capture by the tech borg. They’ve grown up in an era marked by mounting terror about climate change, and in which conventional politics seems woefully insufficient to solve any problems. So Kaczynski’s manifesto resonates.”[58]

In his lifetime, Ted Kaczynski made a huge and lasting impact on society at the time with his criticisms of the system and the consequences of his 17 year bombing campaign. In the end, Ted died at age 81, by suspected suicide,[59] but the consequences of his influence have lasted generations.

[1] Truth Versus Lies (Original Draft).

[2] Ibid.

“[Your hatred of your parents] I think, I am convinced, has its source in your traumatic hospital experience in your first year of life. ...”

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

> Our block of Carpenter Street was part of a working–class neighborhood that was just one step above the slums. As my playmates grew older, some of them began engaging in behavior that approached or crossed the line dividing acceptable childhood mischief from delinquency. For example, two of them got into trouble for trying to set fire to someone’s garage. I had been trained to a much more exacting standard of behavior and wouldn’t participate in the other kids’ mischief. Once, for instance, I was with a bunch of neighborhood kids who waited in ambush for an old rag–picker, pelted him with garbage when he came past, and then ran away. I stood back in the rear and refused to participate, and immediately afterward I went home and told my mother what had happened, because I was shocked at such disrespect being shown to an adult—even if he was only a rag–picker.”

> So it may be that the reason why I ceased to be fully accepted by my Carpenter–Street playmates at around the age of eight or nine was that they saw me as too much of a ‘good boy.’ In any case they did seem to lose interest in my companionship—I was no longer one of the bunch.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ted Kaczynski’s 1979 Autobiography.

[10] Ted Kaczynski’s 1958 Autobiography.

“Beginning in the second or third grade I began to become somewhat unsocial, keeping to myself and seeking the companionship of my comrades less often. This was probably due, in part, to the level of education and culture in my old neighborhood, where no one was interested in science, art, or books”{1}

[11] Truth Versus Lies (Original Draft).

[12] Ted Kaczynski’s 1959 Autobiography.

[13] Studies of Stressful Interpersonal Disputations by Henry Murray. American Psychologist, vol. 18, no. 1 (1963), pp. 28–36. doi:10.1037/h0045502.

> Fourth, a signal is given and the discussion starts, continuing through three differentiated periods as you were told it would. In the second period, however, the lawyer’s criticism becomes far more vehement, sweeping, and personally abusive than you were led to expect. The directions given to the lawyer were the same as you received, except that he was told to anger you and, adhering to a rehearsed and more or less standardized mode of attack, he will almost certainly succeed in doing this, having been successful in all the dyads we have witnessed. Dyad is the convenient four-letter word we use to refer to each of these 18-minute two-person interactions, plus four inactive periods amounting to 9 minutes, i.e., about 27 minutes in all.”

> Fifth, after the termination of the debate, you are taken to a room where you are left alone with the instruction to write down as much as you are able to recall of what was said by the lawyer and by yourself, word for word if possible and in proper sequence.

[14] Excerpt from a letter to the author of ‘Dostoyevsky’s Stalker’.

“I experienced a lasting resentment of Murray and his co-workers. This resentment was not primarily due to the “dyadic disputation” that Chase makes so much of. What I mainly resented was the fact that I had been talked into participating in studies that involved extensive invasion of my privacy—and by people whom I disliked personally. I am quite confident that my experiences with Professor Murray had no significant effect on the course of my life.”

[15] In a letter of May 16, 1991 to his mother Ted wrote:

“There was a good deal of snobbery at Harvard. Of course there were people there from all walks of life, but apparently the system there was run by people who came from the ‘right’ cultural background. This certainly seemed to be the case at Eliot House, anyway. The house master, John Finley, apparently was surrounded by an ingroup or clique, and the people who got to participate in the Christmas play, for example, always seemed to be of the type who would fit in with the clique. The house master often treated me with insulting condescension. He seemed to have a particular dislike for me. I used to think that this was merely because I made no attempt to wear the ‘right’ clothes or to ape Harvard manners, but now I wonder whether plain old–fashioned class snobbery, in the strict sense of the word, might not have had something to do with it. Not long ago I read ‘FDR: a remembrance’ by Joseph Alsop. Alsop had connections with the Harvard set, and he stated in that book that in 1955 John F. Kennedy was not permitted to become a member of the Harvard Board of Overseers because he was an Irish Catholic. Since I entered Harvard 3 years later, in 1958, it seems probable that a good deal of class snobbery must still have existed at Harvard at that time.”

—Truth Versus Lies (Original Draft)

[16] “TED: You can’t live as a free person as a member of a large-scale system. There is another way to live and you don’t have to live the way we do in this system. I’ve been anti-technology ever since 1962. My last year at Harvard was the year when I definitely decided I was against technology.”

—Theresa Kintzs’ Interview with Ted Kaczynski

> We must sit here and take it

> The worst aspect of such evils as air pollution, DDT and the garbage put on TV is not the actual harm that these things do us; the really galling thing about them is that we just have to take what society dishes out, be it good or bad. Individually, there’s nothing we can do about it.

>Theodore J. Kaczynski

—Ted’s Newspaper Mentions Before His Imprisonment

[17] Ted Kaczynski’s 1979 Autobiography.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

> My first thought was to kill somebody I hated and then kill myself before the cops could get me. {I’ve always considered death preferable to long imprisonment.) But, since I now had new hope, I was not ready to relinquish life so easily. So I thought, “I will kill, but I will make at least some effort to avoid detection, so that I can kill again.” Then I thought, well, as long as I am going to throw everything up anyway, instead of having to shoot it out with the cops or something, I will do what I’ve always wanted to do, namely, I will go up to Canada, take off into the woods with a rifle, and try to live off the country. If that doesn’t work out, and if I can get back to civilization before I starve, then I will come back here and kill someone I hate.” What was new here was the fact that I now felt l really had the courage to behave “irresponsibly”.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ted Kaczynski’s Journal of Early Crimes.

> I came back to the Chicago area in May, mainly for one reason: So that I could more safely attempt to murder a scientist, businessman, or the like. Before leaving Montana I made a bomb in a kind of box, designed to explode when the box was opened. This was a long, narrow box. I picked the name of an electrical engineering professor out of the catalogue of the Renssalaer Polytechnic Institute and addressed the bomb — a package to him.

> I took the package to downtown Chicago, intending to mail it from there (this was in late May, I think around the 28th or 29th), but it didn’t fit in mail boxes and the post-office package-drops I checked did not look as if they would swallow such a long package except in one post-office (Merchandise Mart); but that was where I had bought stamps for the package a few days before, so I was afraid to go there again because, going there twice in a short time, my face might be remembered.

> So I took the bomb over to the U. of Illinois Chicago Circle Campus, and surreptitiously dropped it between two parked cars in the lot near the science and technology buildings.

> I hoped that a student ‒ preferably one in a scientific field ‒ would pick it up, and would either be a good citizen and take the package to a post office to be sent to Renssalaer, or would open the package himself and blow his hands off, or get killed.

> I checked the newspapers carefully afterward but could get no information about the outcome of what I did ‒ the papers seem to report only crimes of special importance.

> I have not the least feelilng of guilt about this ‒ on the contrary I am proud of what I did. But I wish I had some assurance that I succeeded in killing or maiming someone.

> I am now working, in odd moments on another bomb.

[23] Ted Kaczynski’s 1979 Autobiography.

[24] Ted Kaczynski’s Journal of Early Crimes.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Bomb explodes in NU; researcher is burned by Patricia Leeds. May 10, 1979. Page 51. Chicago Tribune.

[27] Ted Kaczynski’s Journal of Early Crimes.

[28] Fully Coded Notebooks of Crimes

> In some of my notes I mentioned a plan-for revenge on society, the plan was to blow up an airliner in flight. Late summer and early autumn I constructed a device. Much expense, because I had to go to Gr. Falls to buy materials, including a barometer and many boxes of cartridges for the powder. I put more than a quart of-smoke less powder in a can, rigged barometer so device would-explode at 2000ft. Or conceivably as high as 3500ft. Due-to variation of atmospheric pressure.

> In late October I mailed the package from Chicago as priority mail so it would go by air. Unfortunately plane not destroyed, bomb too weak. Newspaper said was “low power device”. Surprised me.

> Possible explanations… defective barometer. Light touch of barometer needle on contact is not absolutely reliable in transmitting current. I will try again if I can get a better explosive.

> Bomb did not accomplish much. Probably destroyed some mail. At least it gave them a good scare. The papers said the FBI are investigating the incident. The FBI can suck my cock.

> So I came back to Montana early December, now working on another plan.

[30] Package bomb blast injures top executive of United Air Lines. The Dispatch. Moline, Illinois. Jun 11, 1980. Page 9.

[31] Chris Waits and Dave Shors. Unabomber: The Secret Life of Ted Kaczynski. Farcountry Press. 2014. Original link. Archived link.

[32] See Donald Foster’s chapter ‘Play on Woods’ from the book Author Unknown.

[33] Mystery blast kills capital merchant. The Sacramento Bee. Dec 12, 1985. Page 1.

[34] Ted Kaczynski. Message to San Francisco Examiner C-248 [Letter]. Original link. Archived link.

“The bomb that crippled the right arm of a graduate student in electrical engineering and damaged a computer lab at U. of Cal. Berkeley last May was planted by a terrorist group called Freedom Club.”

[35] Ibid.

“To prove that we are the ones who planted to bomb at U. of Cal. last May, we will mention a few details that could be known only to us and the FBI men who investigated the incident. The explosive was contained in an iron pipe of nominal ¾ inch (actually about 13/16 inch) inside diameter. The ends of the pipe were closed with iron plugs secured with iron pins, of 5/16 inch diameter. One of the plugs had the letters FC (for Freedom Club) marked on it. (There was a metal disc attached to the plug to help assure a good seal. If this was not blown off it would be necessary to remove it in order to see the letters FC.) The bomb was ignited by electricity passing through a fine steel filament. The load-wires passing through the plug to the filament were 18 gauge with green insulation. The rest of the wiring was 16 gauge with flesh covered insulation. Six Duracell size D batteries were used. This should be enough to prove that we planted the bomb.”

[36] Ibid.

> 1. The aim of the Freedom Club is the complete and permanent destruction of modern industrial society in every part of the world. This means no more airplanes, no more radios, no more miracle drugs, no more paved roads, and so forth. Today a large and growing number of people are coming to recognize the industrial-technological system as the greatest enemy of freedom. Many evidences of these changing attitudes could be cited. For the moment we content ourselves with mentioning one statistic. “According to a January 1980 poll, only 33 percent of the citizens of the Federal Republic of Germany [West Germany] still believe that technological development will lead to greater freedom; 56 percent think it is more likely to make us less free.” This is from “1984: Decade of the Experts?” – an article by Johanno Strasser in 1934 revisted: Totalitarianism in our century, edited by Irving Howe and published by Harper and Row, 1983. (This article as a whole helps to show the extent to which technology is becoming a target of social rebellion.)

[37] Ibid.

“3. No ideology or political system can get around the hard facts of life in industrial society. Because any form of industrial society requires a high level of organization, all decisions have to be made by a small elite of leaders and experts who necessarily wield all the power, regardless of any political fictions that may be maintained. Even if the motives of this elite were completely unselfish, they would still HAVE TO exploit and manipulate us simply to keep the system running. Thus the evil is in the nature of technology itself.”

[38] S.F. NEWSPAPER DENIES GETTING LETTER IN ‘85 FROM UNABOMBER

[39] Unabomber claims he told motives in ‘85 note

[40] Ted Kaczynski (Author) & Kelli Grant (Curator). Kaczynski and his lawyers [Letter]. Yahoo News. Original link. Archived link.

[41] Religion, Violence and Radical Environmentalism: From Earth First! to the Unabomber to the Earth Liberation Front

[42] Ted Kaczynski. Suggestions for Earth Firsters from FC: K2041G [Letter]. Folder 3, Box 82, Ted Kaczynski papers, University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Library). Original link. Archived link.

[43] Mail bomb kills ad exec. Daily News [Local New York Paper]. Dec 11, 1994. Page 272.

[44] Unabomber kills again. The Sacramento Bee. Apr 25, 1995. Page 1.

[45] Ted Kaczynski. U-7: Letter and envelop from FC to Warren Hoge (Assistant Managing Editor, NY Times) [Letter]. California University of Pennsylvania Special Collections. Original link. Archived link.

[46] Ted Kaczynski. U-6: Letter and envelop from FC to Phillip A. Sharp [Letter]. California University of Pennsylvania Special Collections. Original link. Archived link.

[47] Ted Kaczynski. U-5: Letter and envelop from FC to Richard J. Roberts [Letter]. California University of Pennsylvania Special Collections. Original link. Archived link.

[48] Ted Kaczynski. U-10 : Letter from FC to Washington Post [Letter]. California University of Pennsylvania Special Collections. 1995-06-24. Original link. Archived link.

[49] Ted Kaczynski. U-9: Letter and envelop from “FC” to Warren Hoge [Letter]. California University of Pennsylvania Special Collections. Original link. Archived link.

[50] Ted Kaczynski. U-11: Letter and envelop from “FC” to Rob Guccione (Penthouse) [Letter]. California University of Pennsylvania Special Collections. Original link. Archived link.

[51] Ted Kaczynski. U-8: Letter and envelop from “Frederick Benjamin Isaac Wood” (“FC”) to Jerry Roberts (Editorial Page Editor, San Francisco Chronicle) [Letter]. California University of Pennsylvania Special Collections. Original link. Archived link.

[52] William Claiborne. Unabomber Threatens, Then Calls It a Prank [Essay]. Washington Post. June 29, 1995. Original link. Archived link.

[53] Industrial Society and Its Future (Washington Post Version). September 19, 1995. Washington Post. PDF Scan of the original Paper. Archived text version.

[54] David Skrbina said “I think at some point I asked him about that. He said basically he ‘wanted to drive off the left before they even got to the meat of the manifesto.’ So, that’s why he put that stuff up front.” —A text dump on Counter-Currents

[55] Ted Kaczynski’s 1969 Journal. California University Archive Source: Part #1, #2 & #3). Archived Link.

[56] The Terrorist Tract That's Hot Reading by Marc Fisher. September 23, 1995. Washington Post.

[57] Ted Kaczynski. Progress versus Liberty [Essay]. California University of Pennsylvania Special Collections. 1971. Original link. Archived link.

[58] Gen Z’s worship of the Unabomber

[59] ‘Unabomber’ Ted Kaczynski Hanged Himself in Prison Cell...911 Audio Reveals

{1} Though it’s worth noting Ted says he thinks his mother made him write the reason why, and that he doesn’t now think that to be the case:

“Actually, I wasn’t so terribly interested in science, art, or books myself. The autobiographical sketch was part of an application for admission to Harvard and therefore was written under the close supervision of my mother.”

—Truth Versus Lies (Original Draft).