Andrew Boyd

Beautiful Trouble

A Toolbox for Revolution

Anger works best when you have the moral high ground / Russell

Beware the tyranny of structurelessness

Challenge patriarchy as you organize

Choose tactics that support your strategy

Consensus is a means, not an end

Don’t just brainstorm, artstorm!

Don’t mistake your group for society

If protest is made illegal, make daily life a protest

Lead with sympathetic characters

Maintain nonviolent discipline

Make your actions both concrete and communicative

No one wants to watch a drum circle

Play to the audience that isn’t there

Put movies in the hands of movements

Put your target in a decision dilemma

Simple rules can have grand results

Take leadership from the most impacted

Use others’ prejudices against them

Use the law, don’t be afraid of it

Use your radical fringe to slide the Overton window

Write your own Principle / You

Expressive and instrumental actions

Temporary Autonomous Zone (TAZ)

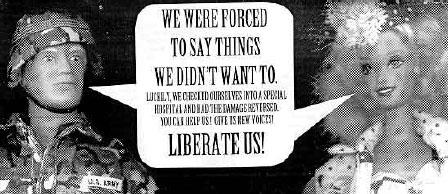

Barbie Liberation Organization

Clandestine Insurgent Rebel Clown Army (CIRCA)

Dow Chemical apologizes for Bhopal

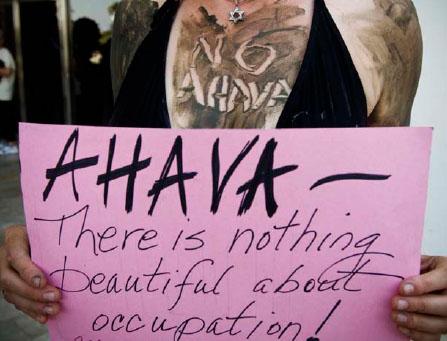

The Stolen Beauty boycott campaign

April 6 Youth Movement (Egypt)

Artist Network of Refuse & Resist!

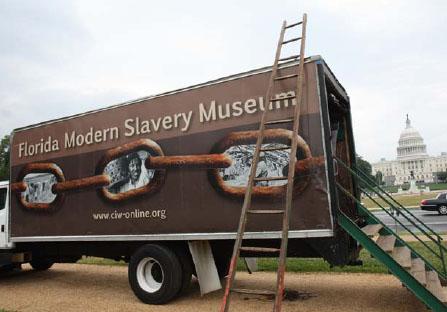

The Coalition of Immokalee Workers

The Deconstructionist Institute for Surreal Topology

Design Studio for Social Intervention

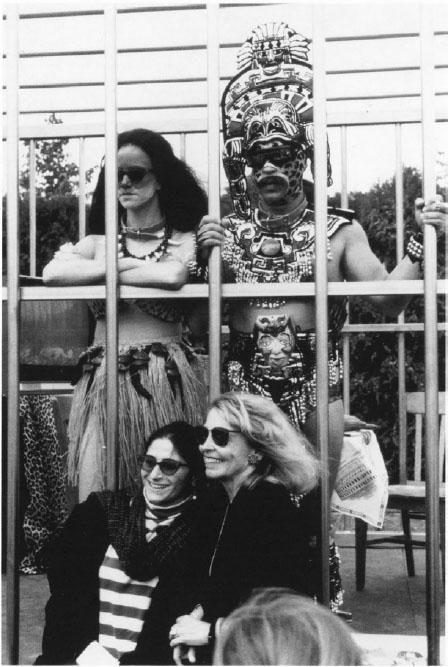

Guillermo Gómez-Peña & La Pocha Nostra

Iraq Veterans Against the War (IVAW)

Los Angeles Poverty Department (LAPD)

Reverend Billy and the Church of Earthalujah

The Zapatista Army of National Liberation

Creative Commons License

All essays © 2012 Beautiful Trouble by various authors, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license, including reprint rights and foreign language editions, may be available through the publisher.

Published by OR Books, New York and London

Visit our website at www.orbooks.com

First printing 2012

Cover illustration by Andy Menconi

Printed by BookMobile, USA, and CPI, UK.

The printed edition of this book comes on Forest Stewardship Council-certified, 30% recycled paper. The printer, BookMobile, is 100% wind-powered.

paperback ISBN: 978-1-935928-57-7

ebook ISBN: 978-1-935928-58-4

Beautiful Trouble Team

Co-editor & wrangler-in-chief / Andrew Boyd

Co-editor / Dave Oswald Mitchell

Master of logistics / Zack Malitz

Photo editor / Margaret Campbell

Web maker & project agitator / Phillip Smith

Consultant-in-chief / Nadine Bloch

Wordhorse / Joshua Kahn Russell

Fellow traveler / Maxine Schoefer-Wulf

Participating Organizations

Agit-Pop/The Other 98%, The Yes Men/Yes Lab, CODEPINK, smartMeme,

The Ruckus Society, Beyond the Choir, The Center for Artistic Activism,

Waging Nonviolence, Alliance of Community Trainers and Nonviolence International.

Contributors

Rae Abileah, Ryan Acuff, Celia Alario, Phil Aroneanu, Peter Barnes, Jesse Barron, Andy Bichlbaum, Nadine Bloch, Kathryn Blume, L.M. Bogad, Josh Bolotsky, Mike Bonanno, Andrew Boyd, Kevin Buckland, Margaret Campbell, Doyle Canning, Samantha Corbin, Yutaka Dirks, Stephen Duncombe, Mark Engler, Simon Enoch, Jodie Evans, John Ewing, Brian Fairbanks, Bryan Farrell, Janice Fine, Lisa Fithian, Christian Fleming, Elisabeth Ginsberg, Stan Goff, Arun Gupta, Silas Harrebye, Judith Helfand, Daniel Hunter, Sarah Jaffe, John Jordan, Dmytri Kleiner, Sally Kohn, Steve Lambert, Anna Lee, Stephen Lerner, Zack Malitz, Nancy Mancias, Duncan Meisel, Matt Meyer, Dave Oswald Mitchell, Tracey Mitchell, George Monbiot, Brad Newsham, Gaby Pacheco, Mark Read, Patrick Reinsborough, Simon Roel, Joshua Kahn Russell, Leónidas Martín Saura, Levana Saxon, Maxine Schoefer-Wulf, Nathan Schneider, Kristen Ess Schurr, John Sellers, Rajni Shah, Brooke Singer, Matt Skomarovsky, Andrew Slack, Phillip Smith, Jonathan Matthew Smucker, Starhawk, Eric Stoner, Jeremy Varon, Virginia Vitzthum, Harsha Walia, Jeffery Webber and the Coalition of Immokalee Workers.

The role of the artist in the social structure follows the need of the changing times:

IN TIME OF SOCIAL STASIS: to activate

IN TIME OF GERMINATION: to invent fertile new forms

IN TIME OF REVOLUTION: to extend the possibilities of peace and liberty

IN TIME OF VIOLENCE: to make peace

IN TIME OF DESPAIR: to give hope

IN TIME OF SILENCE: to sing out

—Judith Malina, “The Work of an Anarchist Theater”

Dedication

A.B.

To my mentors in the struggle, both far away — George Orwell, Abbie Hoffman, Subcomandante Marcos — and close at hand — Bob Rivera, Dennis Livingston, Janice Fine, Mike Prokosch, Chuck Collins, John Sellers & the RTS/B4B crew.

D.O.M.

For the silent leaders behind every victory “who strain in the mud and the muck to move things forward, who do what has to be done, again and again” (Marge Piercy).

Contents

INTRODUCTION / Boyd & Mitchell

Advanced leafleting / Lambert & Boyd

Artistic vigil / Boyd

Banner hang / Bloch

Blockade / Russell

Creative disruption / Mancias

Creative petition delivery / Meisel

Debt strike / Jaffe & Skomarovsky

Détournement/Culture jamming / Malitz

Direct action / Russell

Distributed action / Aroneanu

Electoral guerrilla theater / Bogad

Eviction blockade / Acuff

Flash mob / D. Mitchell & Boyd

Forum theater / Saxon

General strike / Lerner

Guerrilla projection / Corbin & Read

Hoax / Bonanno

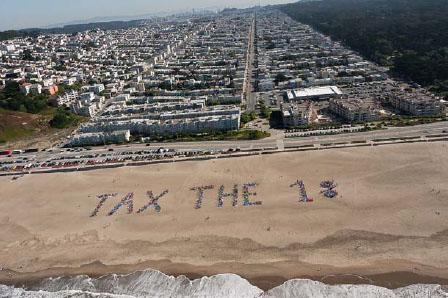

Human banner / Newsham

Identity correction / Bichlbaum

Image theater / Saxon

Infiltration / Bichlbaum

Invisible theater / T. Mitchell

Mass street action / Sellers & Boyd

Media-jacking / Reinsborough, Canning & Russell

Nonviolent search and seizure / Hunter

Occupation / Russell & Gupta

Prefigurative intervention / Boyd

Public filibuster / Hunter

Strategic nonviolence / Starhawk & ACT

Trek / Bloch

Write your own TACTIC / You

Anger works best when you have the moral high ground / Russell

Anyone can act / Bichlbaum

Balance art and message / Buckland, Boyd & Bloch

Beware the tyranny of structurelessness / Bolotsky

Brand or be branded / Fleming

Bring the issue home / Abileah & Evans

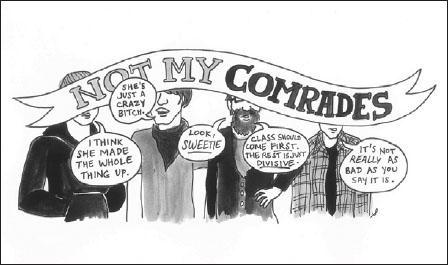

Challenge patriarchy as you organize / Walia

Choose tactics that support your strategy / Fine

Choose your target wisely / Dirks

Consensus is a means, not an end / Walia

Consider your audience / Kohn

Debtors of the world, unite! / Kleiner

Delegate / Bolotsky & Boyd

Do the media’s work for them / Bichlbaum

Don’t dress like a protester / Boyd

Don’t just brainstorm, artstorm! / Saxon

Don’t mistake your group for society / Bichlbaum

Enable, don’t command / Blume

Escalate strategically / Smucker

Everyone has balls/ovaries of steel / Bichlbaum

If protest is made illegal, make daily life a protest / Bloch

Kill them with kindness / Boyd

Know your cultural terrain / Duncombe

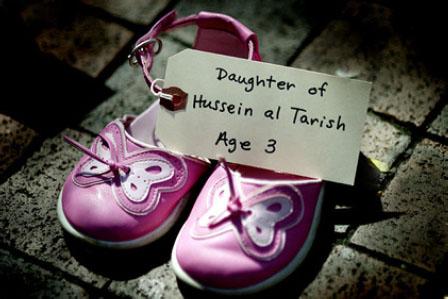

Lead with sympathetic characters / Canning & Reinsborough

Maintain nonviolent discipline / Schneider

Make new folks welcome / Smucker

Make the invisible visible / Bloch

Make your actions both concrete and communicative / Russell

No one wants to watch a drum circle / Lambert

Pace yourself / T. Mitchell

Play to the audience that isn’t there / Bichlbaum & Boyd

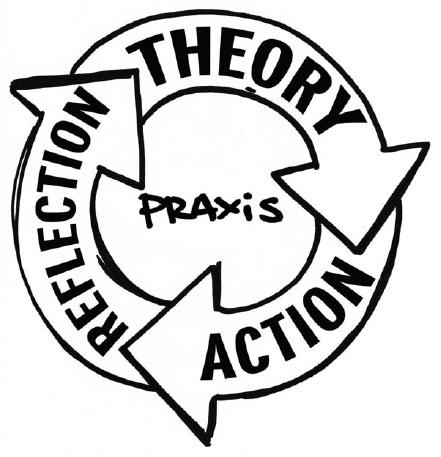

Praxis makes perfect / Russell

Put movies in the hands of movements / Helfand & Lee

Put your target in a decision dilemma / Boyd & Russell

Reframe / Canning & Reinsborough

Seek common ground / Smucker

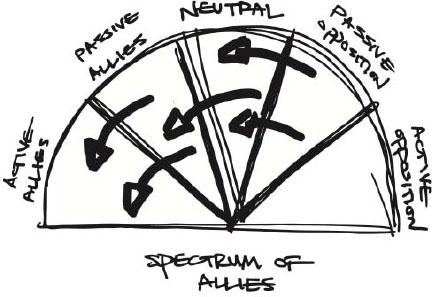

Shift the spectrum of allies / Russell

Show, don’t tell / Canning, Reinsborough & Buckland

Simple rules can have grand results / Boyd

Stay on message / Alario

Take leadership from the most impacted / Russell

Take risks, but take care / Russell

Team up with experts / Singer

Think narratively / Canning & Reinsborough

This ain’t the Sistine Chapel / Bloch

Turn the tables / Read

Use others’ prejudices against them / Bloch

Use the Jedi mind trick / Corbin

Use the law, don’t be afraid of it / Bichlbaum & Bonanno

Use the power of ritual / Boyd

Use your radical fringe to slide the Overton window / Bolotsky

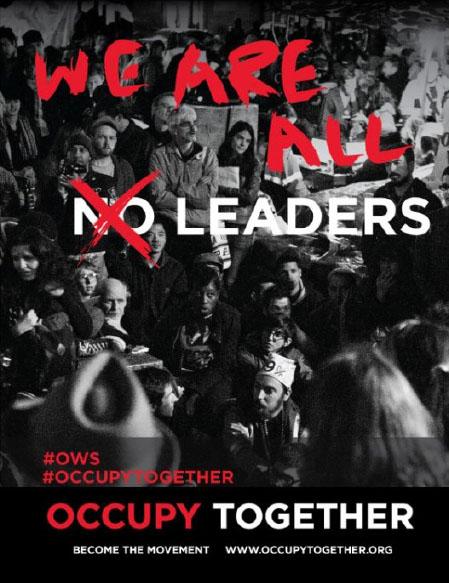

We are all leaders / Smucker

Write your own PRINCIPLE / You

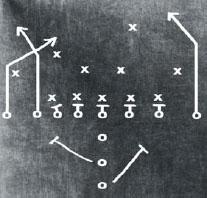

Action logic / Boyd & Russell

Alienation effect / Bogad

Anti-oppression / Fithian & D. Mitchell

Capitalism / Webber

Commodity fetishism / Malitz

The commons / Barnes

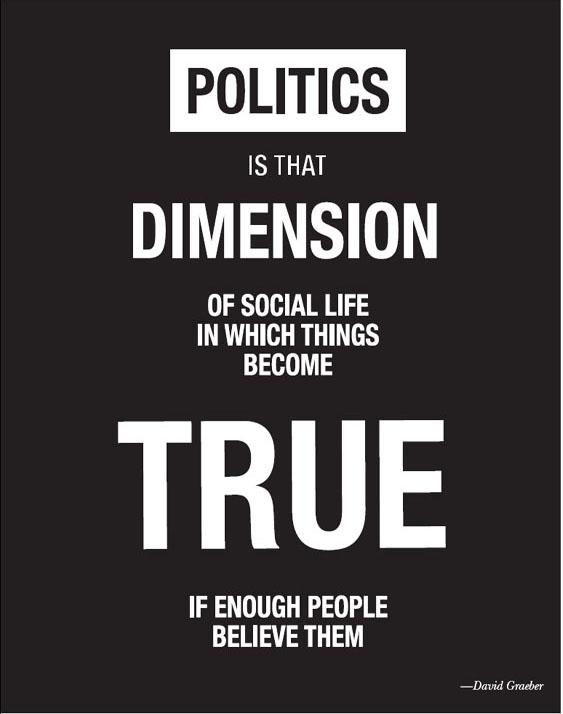

Cultural hegemony / Duncombe

Debt revolt / Kleiner

Environmental justice / Campbell

Ethical spectacle / Duncombe

Expressive and instrumental actions / Smucker, Russel & Malitz

Floating signifier / Smucker, Boyd & D. Mitchell

Hamoq & hamas / Monbiot

Hashtag politics / Meisel

Intellectuals and power / Malitz

Memes / Reinsborough & Canning

Narrative power analysis / Reinsborough & Canning

Pedagogy of the Oppressed / Saxon & Vitzthum

Pillars of support / Stoner

Points of intervention / Reinsborough & Canning

Political identity paradox / Smucker

The propaganda model / Enoch

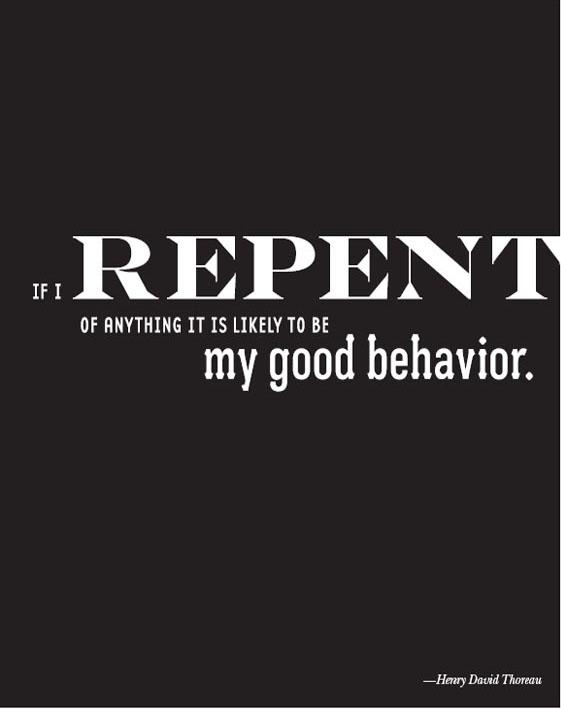

Revolutionary nonviolence / Meyer

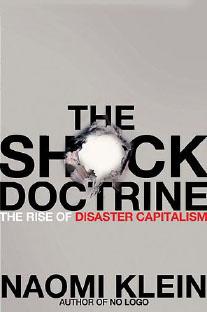

The shock doctrine / Engler

The social cure / Farrell

Society of the spectacle / D. Mitchell

The tactics of everyday life / Goff

Temporary Autonomous Zone (TAZ) / Jordan

Theater of the Oppressed / Saxon

Write your own THEORY / You

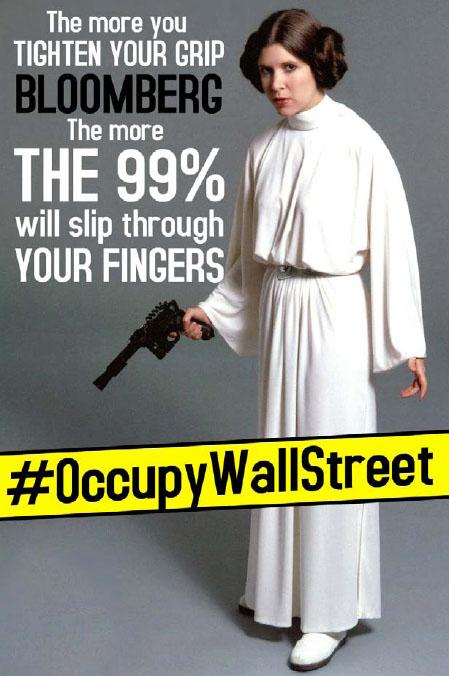

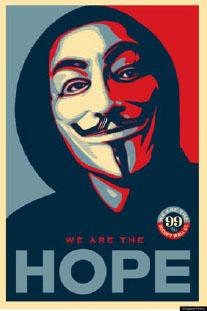

99% bat signal / Read

Barbie Liberation Organization / Bonanno

Battle in Seattle / Sellers

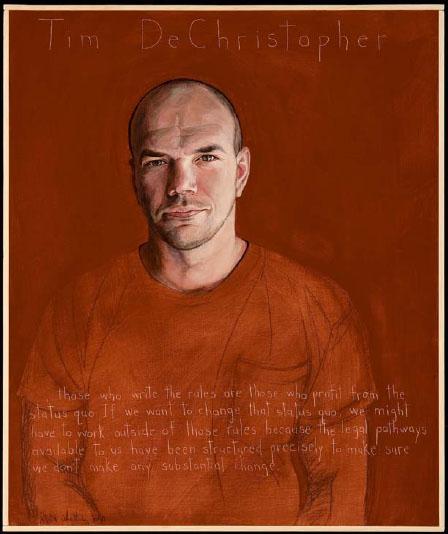

Bidder 70 / Bichlbaum & Meisel

The Big Donor Show / Harrebye

Billionaires for Bush / Varon, Boyd & Fairbanks

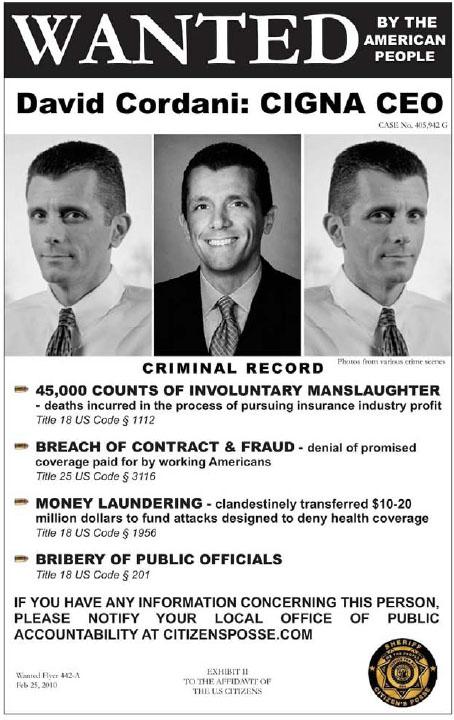

Citizens’ Posse / Sellers

Clandestine Insurgent Rebel Clown Army / Jordan

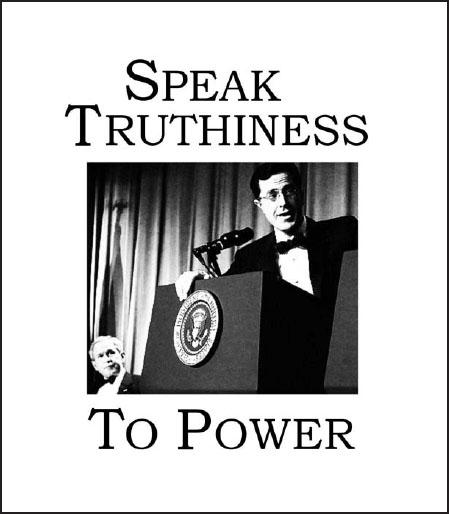

Colbert roasts Bush / Ginsberg

The Couple in the Cage / Ginsberg

Daycare center sit-in / Boyd

Dow Chemical apologizes for Bhopal / Bonanno

Harry Potter Alliance / Slack

Justice for Janitors / Fithian

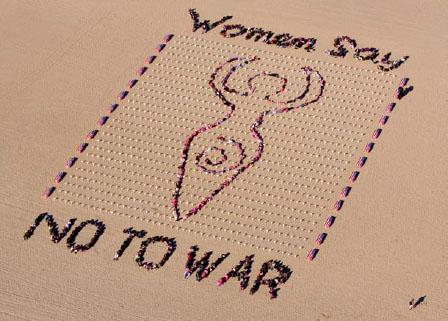

Lysistrata project / Blume

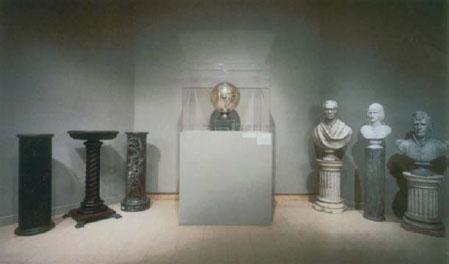

Mining the museum / Ginsberg

Modern-Day Slavery Museum / CIW

The Nihilist Democratic Party / Roel & Ginsberg

Public Option Annie / Boyd

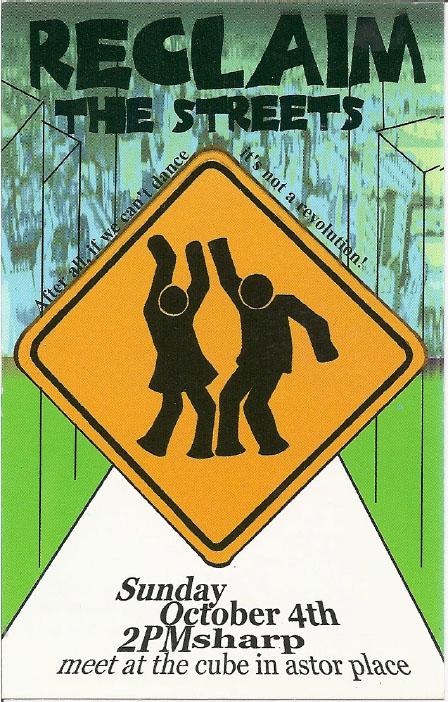

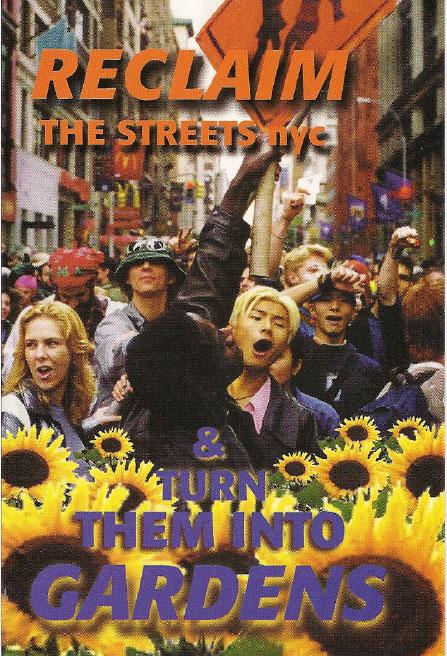

Reclaim the Streets / Jordan

The salt march / Bloch

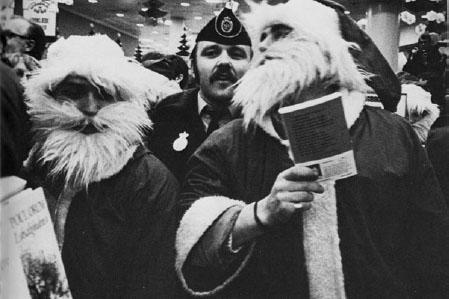

Santa Claus Army / Ginsberg

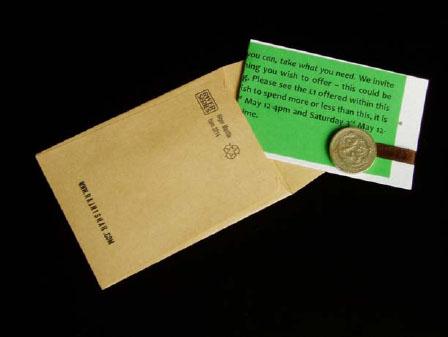

Small gifts / Shah

Stolen Beauty boycott campaign / Schurr

Streets into gardens / Read

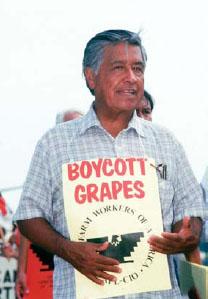

Taco Bell boycott / Dirks

Tar sands action / Meisel & Russell

Teddy-bear catapult / D. Mitchell

Trail of Dreams / Pacheco

Virtual Streetcorners / Ewing

Whose tea party? / Boyd

Wisconsin Capitol Occupation / Meisel

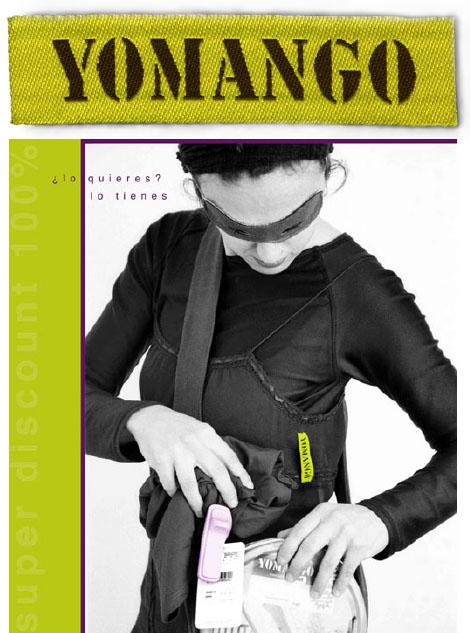

Yomango / Saura

Write your own CASE STUDY / You

Malitz, Schoefer-Wulf and Barron

RESOURCES

CONTRIBUTOR BIOS

PARTICIPATING ORGANIZATIONS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Introduction

By Andrew Boyd & Dave Oswald Mitchell

“The clowns are organizing. They are organizing. Over and out.”

—Overheard on UK police radio during action

by Clandestine Insurgent Rebel Clown Army, July 2004 (see p. 304)

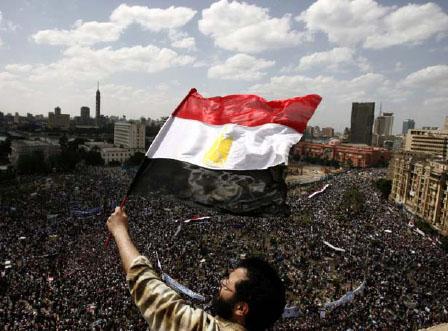

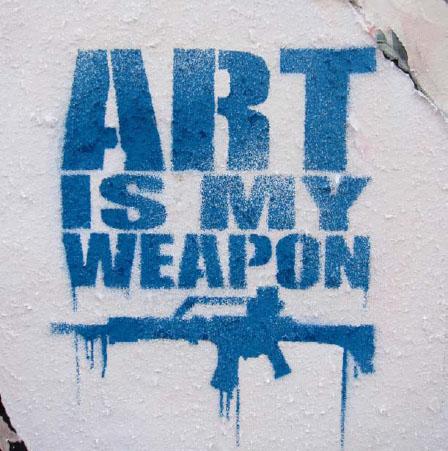

“Human salvation,” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. argued, “lies in the hands of the creatively maladjusted,” and recent historical events are proving him as prescient as ever. As the recent wave of global revolt has swept through Iceland, Bahrain, Egypt, Spain, Greece, Chile, the United States and elsewhere, the tools at activists’ disposal, the terrain of struggle and the victories that suddenly seem possible are quickly evolving. The realization is rippling through the ranks that, if deployed thoughtfully, our pranks, stunts, flash mobs and encampments can bring about real shifts in the balance of power. In short, large numbers of people have seen that creative action gets the goods — and have begun to act accordingly. Art, it turns out, really does enrich activism, making it more compelling and sustainable.

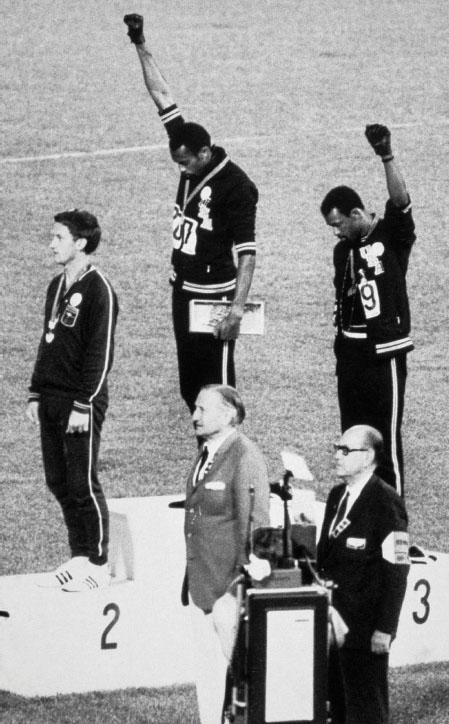

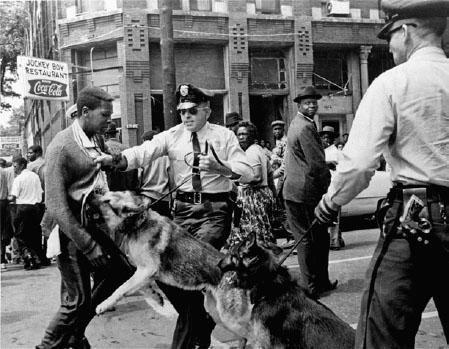

This blending of art and politics is nothing new. Tactical pranks go back at least as far as the Trojan Horse. Jesus of Nazareth, overturning the tables of the money changers, mastered the craft of political theater 2,000 years before Greenpeace. Fools, clowns and carnivals have always played a subversive role, while art, culture and creative protest tactics have for centuries served as fuel and foundation for successful social movements. It’s hard to imagine the labor movements of the 1930s without murals and creative street actions, the U.S. civil rights movement without song, or the youth upheavals of the late 1960s without guerrilla theater, Situationist slogans or giant puppets floating above a rally.

Today’s culture jammers and political pranksters, however, shaped by the politics and technologies of the new millennium, have taken activist artistry to a whole new level. The current political moment of looming ecological catastrophe, deepening inequality, austerity and unemployment, and growing corporate control of government and media offers no choice but to fight back. At the same time, the explosion of social media and many-to-many communication technologies has put powerful new tools at our disposal. We’re building rhizomatic movements marked by creativity, humor, networked intelligence, technological sophistication, a profoundly participatory ethic and the courage to risk it all for a livable future.

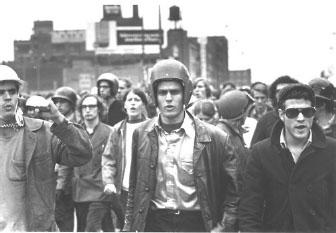

This new wave of creative activism first drew mainstream attention in 1999 at the Battle in Seattle, but it didn’t start there. In the 1980s and ’90s, groups like ACT-UP, Women’s Action Coalition and the Lesbian Avengers inspired a new style of high-concept shock politics that both empowered participants and shook up public complacency. In 1994, the Zapatistas, often described as the first post-modern revolutionary movement, awakened the political imaginations of activists around the world, replacing the dry manifesto and the sectarian vanguard with fable, poetry, theater and a democratic movement of movements against global capitalism. The U.S. labor movement, hit hard by globalization, began to seek out new allies, including Earth First!, which was pioneering new technologies of radical direct action in the forests of northern California. The Reclaim the Streets model of militant carnivals radiated out from London, and the “organized coincidences” of Critical Mass bicycle rides provided a working model of celebratory, self-organizing, swarm-like protest. Even the legendary Burning Man festival, while not explicitly political, introduced thousands of artists and activists to the lived experience of participatory culture, radical self-organization and a gift economy. The Burning Man slogans “No spectators!” and “You are the entertainment!” were just as evident on the streets of Seattle as they are in the Nevada desert each summer.

Through the last decade, though we’ve lost ground on climate, civil liberties, labor rights and so many other fronts, we’ve also seen an incredible flourishing of creativity and tactical innovation in our movements, both in the streets and online. Whether it was the Yes Men prank-announcing the end of the WTO (and everyone believing it!), or the Billionaires for Bush parading their “Million Billionaire March” past the Republican National Convention, or MoveOn staging a millions-strong virtual march on Washington to protest the Iraq War, our movements were forging new tools and a new sensibility that got us through those dark times. Every year, new terms had to be invented just to track our own evolution: flash mobs, virtual sit-ins, denial-of-service attacks, media pranks, distributed actions, viral campaigns, subvertisements, culture jamming, etc.

As a participant in many of these movements, Andrew Boyd, this project’s instigator and co-editor, had been kicking around the idea for Beautiful Trouble for almost a decade before he teamed up with web maker Phillip Smith and editor Dave Oswald Mitchell to make it happen. Little did we know what kind of a year 2011 would turn out to be.

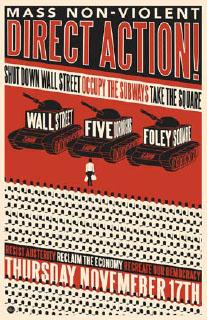

By the time our expanding team of collaborators was hammering out our first proof-of-concept modules, Egyptian revolutionaries were phoning in pizza orders to the students and workers occupying the Capitol in Madison, Wisconsin. A few months later, as we were gearing up for our big finishing push, Occupy Wall Street went global. Suddenly, half the people we were trying to wrangle modules out of were working double overtime for the revolution. The excuses for why these writer/ activists were missing their deadlines were priceless (and often airtight, since we could simply confirm them by checking the day’s news!): Sorry, I had to shut down Wall Street with a blockadecarnival while distracting the cops with 99,000 donuts. Or: I’ll get that rewrite to you as soon as me and my 12,000 closest friends finish surrounding the White House to save the climate as we know it. Or: Hold on, I have to sneak a virtuoso guitarist into the most heavily guarded spot on earth that day (the APEC summit in Honolulu) to serenade Obama and Chinese President Hu Jintao with a battle cry from the 99%. Or: Shit, I know I said I’d write up that guerrilla projection tactic thing you wanted, but I can’t because, get this, I’m DOING ONE RIGHT NOW see: CASE: 99% bat signal. Somehow, though, we managed to keep moving the project forward through the thick of the American Autumn.

Beautiful Trouble lays out the core tactics, principles and theoretical concepts that drive creative activism, providing analytical tools for changemakers to learn from their own successes and failures. In the modules that follow, we map the DNA of these hybrid art/action methods, tease out the design principles that make them tick and the theoretical concepts that inform them, and then show how all of these work together in a series of instructive case studies.

Creative activism offers no one-size-fits-all solution, and neither do we. Beautiful Trouble is less a cookbook than a pattern language,[1] seeking not to dictate strict courses of action but instead offer a matrix of flexible, interlinked tools that practitioners can pick and choose among, applying them in unique ways varying with each situation they may face.

The material is organized into five different categories of content:

Tactics

Specific forms of creative action, such as a flash mob or an occupation.

Principles

Hard-won insights that can guide or inform creative action design.

Theories

Big-picture concepts and ideas that help us understand how the world works and how we might go about changing it.

Case studies

Capsule stories of successful and instructive creative actions, useful for illustrating how principles, tactics and theories can be successfully applied in practice.

Practitioners

Brief write-ups of some of the people and groups that inspire us to be better changemakers.

Each of these modules is linked to related modules, creating a nexus of key concepts that could, theoretically, expand endlessly. As the form took hold and the number of participating organizations and contributing writers grew, what began as a how-to book of prankster activism gradually expanded into a Greenpeace-esque direct action manual and from there grew further to address issues of mass organizing and emancipatory pedagogy and practice.

While we’ve sought to cast as wide a net as possible, drawing in over seventy experienced artist-activists and ten grassroots organizations to distill their wisdom, we are painfully aware of the geographical, thematic and cultural limitations of the collection of modules as it currently stands. We’ve included in the book blank templates for each content type, and the capacity to submit or suggest modules on the website, in the hopes that readers will be inspired to identify, and fill in, some of these gaps.

We encourage readers to explore our website, beautifultrouble.org, which is more than simply an appendage to the book, but in fact stands as perhaps the fullest expression of the project. In an easily navigable form, the website includes all the book’s content as well as material that, due to constraints of both space and time, we were unable to include in this print edition. With the participation of readers, the body of patterns that constitute Beautiful Trouble could continue to evolve and expand, attracting new contributors and keeping abreast of emerging social movements and their tactical innovations.

Millions around the world have awoken not just to the need to take action to reverse deepening inequality and ecological devastation, but to our own creative power to do so. You have in your hands a distillation of ideas gleaned from those on the front lines of creative activism. But these ideas are nothing until they’re acted upon. We look forward to seeing what you do with them.

January 2012

Tactics

MODES OF ACTION

Specific forms of creative action, such as a flash mob or an occupation.

“Tactics… lack a specific location, survive through improvisation, and use the advantages of the weak against the strong.”

—Paul Lewis et al.[2]

Every discipline has its forms. Soldiers can choose to lay siege or launch a flanking maneuver. Writers can try their hand at biography or flash fiction. Likewise, creative activists have their own repertoire of forms. Some, like the sit-in and the general strike, are justly famous; others, like flash mobs and culture jamming, have a newfangled pop appeal; yet others – like debt strike, prefigurative intervention, eviction blockade – are mostly unknown but could soon make their appearance on the stage of history. If art truly is a hammer with which to shape the world, it’s time to gear up.

Advanced leafleting

Steve Lambert

Andrew Boyd

COMMON USES

To get important information into the right hands.

Leafleting is the bread-and-butter of many campaigns. It’s also annoying and ineffective, for the most part. How many times have you taken a leaflet just because you forgot to pull your hand back in time, only to throw it in the next available trash can? Or you’re actually interested and stick it in your pocket, but then you never get around to reading it because it’s a block of tiny, indecipherable text? Well, if that’s what a committed, world-caring person like you does, just imagine what happens to all the leaflets you give out to harried career-jockeys as they rush to or from work.

“If you’re doing

standard leafleting,

you’re wasting

everybody’s time. What you

need is advanced

leafleting.”

In a word, if you’re doing standard leafleting, you’re wasting everybody’s time. What you need is advanced leafleting.

In advanced leafleting, we acknowledge that if you’re going to hand out leaflets like a robot, you might as well have a robot hand them out. Yes, an actual leafleting robot. In 1998, the Institute for Applied Autonomy built “Little Brother” a small, intentionally cute, 1950s-style metal robot to be a pamphleteer. In their tests, strangers avoided a human pamphleteer, but would go out of their way to take literature from the robot.

Make it fun. Make it unusual. Make it memorable. Don’t just hand out leaflets. Climb up on some guy’s shoulders and hand out leaflets from there, as one of the authors of this piece did as a student organizer. (He also tried the same tactic hitchhiking, with less stellar results.) The shareholder heading into a meeting is more likely to take, read and remember the custom message inside the fortune cookie you just handed her than a rectangle of paper packed with text.

Using theater and costumes to leaflet can also be effective. In the 1980s, activists opposed to U.S. military intervention in Central America dressed up as waiters and carried maps of Central America on serving trays, with little green plastic toy soldiers glued to the map. They would go up to people in the street and say, “Excuse me, sir, did you order this war?” When the “no” response invariably followed, they would present an itemized bill outlining the costs: “Well, you paid for it!” Even if the person they addressed didn’t take the leaflet, they’d get the message.

The point is, leafleting is not a bad tactic. It’s still a good way to tell passersby what you’re marching for, why you’re making so much noise on a street corner or why you’re setting police cars on fire. But people are more likely to take your leaflet, read it, and remember what it’s all about if you deliver it with flair. Or ice cream.

KEY PRINCIPLE

at work

KILL THEM WITH KINDNESS: ’Nuff said. Pissing people off won’t do your cause any favors, so don’t piss people off. Disarm with charm, and maybe your audience will let their guard down long enough to hear what you have to say.

OTHER PRINCIPLES AT WORK:

Show, don’t tell

Consider your audience

Balance art and message

Stay on message

Related:

TACTICS

Creative petition delivery

Creative disruption

Mass street action

Street theater web

Electoral guerilla theater

Guerrilla newspaper web

CASE STUDIES

New York Times “Special Edition” web

PRACTITIONERS

Center for Tactical Magic Institute for Applied Autonomy WAG

FURTHER INSIGHT

Institute for Applied Autonomy, “Little Brother”

http://www.appliedautonomy.com/lb.html

Center for Tactical Magic, “The Tactical Ice Cream Unit”

http://trb.la/y0mgjs

Artistic vigil

Andrew Boyd

COMMON USES

To mourn the death of a public hero; to link a natural disaster or public tragedy to a political message; to protest the launch of a war.

The word vigil comes from the Latin word for wakefulness, and refers to a practice of keeping watch through the night over the dead or dying. Compared to the blustery pronouncements of a rally, a candlelight vigil offers a more soulful and symbolically potent expression of dissent.

Unfortunately, routine and self-righteousness can strip vigils of their power. In the American peace movement of the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s, the “candlelight vigil” — all too often a handful of dour people silently holding candles — became a standard, and fatally predictable, form of protest.

An artistic vigil, on the other hand, brings a more artful touch. This doesn’t necessarily mean costumes and face paint and puppets (though it could). It means thoughtful symbolism, the right tone and a distinct look and feel that clearly convey the meaning of the vigil. An artistic vigil often draws upon ritual elements see PRINCIPLE: Use the power of ritual to both deepen the experience of participants and demonstrate that experience to observers.

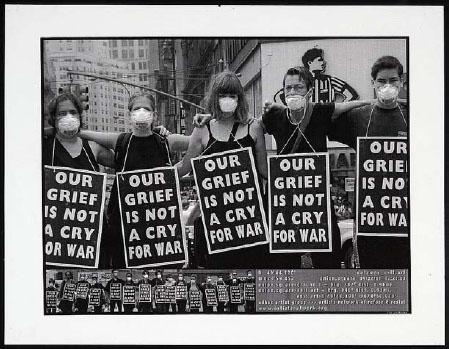

“Our Grief is not a Cry for War” vigils organized by the Artists’ Network of Refuse & Resist in New York City in the wake of 9/11. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Exit Art’s “Reactions” Exhibition Collection [reproduction number, e.g., LC-USZ62-123456]

A good example is the series of “Our Grief Is Not a Cry for War” vigils organized by the Artists’ Network of Refuse & Resist in New York City in the wake of 9/11. People were asked to wear a dust mask (common in NYC after 9/11), dress all in black (common in NYC all the time), show up at Times Square at exactly 5 pm, and remain absolutely silent. Each participant held a sign that read “Our Grief Is Not a Cry for War.” These vigils were silent and solemn, but there was a precision to the message that gave them a visceral potency in that emotionally raw time, for participants and observers alike.

The most famous vigils of the late twentieth century were probably those organized by the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, a group of Argentinian women whose children were disappeared by Argentina’s 70s-era military dictatorship. By gathering every Thursday for more than a decade in the plaza in front of the Presidential Palace, they not only kept vigil for their lost loved ones, but also kept pressure on the government to answer for its crimes.

The “artistry” of a vigil can be exceedingly complex, or as simple as a few basic rituals. The simple fact of women wearing black and gathering in silence on Fridays gives shape and presence to the Women in Black worldwide network of vigils. Begun by Israeli women during the First Intifada to protest the occupation of Palestine, it has since expanded across the globe and embraced broader anti-war and pro-justice themes, but nonetheless maintains its distinctive character. At the other end of the spectrum, artist Suzanne Lacy has created complex works of art in which victims of sexual violence stand vigil amidst the art installations that tell their stories.

KEY PRINCIPLE

at work

USE THE POWER OF RITUAL: Compared to the average political event, a ritual is expected to have a certain gravitas, a higher level of emotional integrity, even a transcendent quality for participants. Like all rituals, a vigil should work at both the personal and political levels. It should offer a sacred experience for participants while effectively reaching out to nonparticipants. The more these two goals align, the more powerful the experience is for the participants and the more powerful the impact on the broader public.

OTHER PRINCIPLES AT WORK:

Know your cultural terrain

No one wants to watch a drum circle

Show, don’t tell

Simple rules can have grand results

Consider your audience

Balance art and message

Related:

TACTICS

Image theater

Distributed action

Advanced leafleting

THEORIES

Action logic

Ethical spectacle

Hamoq & hamas

Narrative power analysis

PRACTITIONERS

Artists’ Network of Refuse & Resist Women In Black Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo Suzanne Lacy Arlington West Bread and Puppet Theater “I Dream Your Dream”

FURTHER INSIGHT

Kelly, Jeff. “The Body Politics of Suzanne Lacy.” But Is It Art? Edited by Nina Felshin. Seattle: Bay Press, 1994.

T.V. Reed. The Art of Protest: Culture and Activism from the Civil Rights Movement to the Streets of Seattle. University of MN, 2005.

Banner hang

Nadine Bloch

COMMON USES

To boldly articulate a demand; to rebrand a target; to provide a message frame or larger- than-life caption for an action.

What better way to air the dirty laundry of an irresponsible institution than to hang a giant banner over its front door? A banner drop can also be an effective way to frame or contextualize an upcoming event or protest see TACTIC: Reframe. Banner hangs can also function as public service announcements to alert the public of an injustice or a dangerous situation.

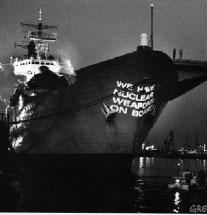

Banner hangs can be as low-tech and low-risk as several bedsheets tied to road overpasses decrying the Iraq War, but the ones that really pack a punch involve large pieces of cloth or netting deployed at great heights, often by experienced climbers.

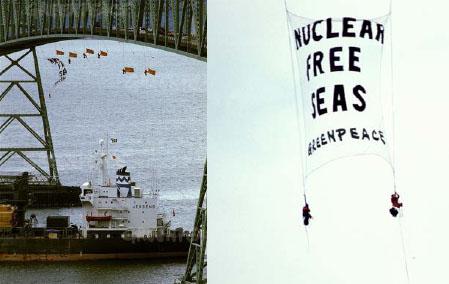

Regardless of the level of risk or complexity, all effective banner hangs start with a clear goal (you have a goal, right?!), and fall into two broad categories: communicative (concise protest statements), and concrete (blockade elements that directly disrupt business as usual) see PRINCIPLE: Make your actions both concrete and communicative. In 1991, in a great example of a banner hang with a concrete goal, small communities in the Pacific Northwest asked for help to stop nuclear warships from entering Clatsop County, Oregon, a designated nuclear-free zone on the Columbia River. An enormous net banner was deployed from the Astoria Bridge, affixed below the span where it would be difficult to remove,and weighted by the climbers’ bodies themselves. The action succeeded in delaying the warships’ entrance while educating the area on the issue.

Most banner hangs, however, tend to be communicative. Take, for instance, the banner hung from a crane in downtown Seattle in November 1999 see CASE: Battle in Seattle just before the opening of the World Trade Organization meeting. The banner messaging was as clear as day: an iconic visual of a street sign with arrows pointing in opposite directions: democracy this way, WTO that way. This was a classic “framing action.” Hung on the eve of a big summit meeting and a huge protest, the banner made it clear what all the fuss to come was really about: a basic struggle of right and wrong; the People vs.WTO.

When there is no crane, bridge or building to hang your banner from, large helium-filled weather balloons have been used to raise everything from CODEPINK’s “pink slip for President George Bush” in front of the White House to a banner deployed from a houseboat on the East River in New York with a message for the UN. Smaller balloons have been used to raise banners indoors in the atriums of malls or corporate or government buildings.

POTENTIAL PITFALLS: If the banner hang requires specific climbing skills or tools, do not skimp on training, scouting, or the quality of gear. Cutting corners could result in the banner snagging, the team being detained before the banner drops, or someone getting seriously injured or killed. Pay attention to changing weather conditions that could turn a proverbial walk in the park into a life-threatening situation see PRINCIPLE: Take risks, but take care. Also, make sure that lighting, lettering, height of building and other factors are taken into account to ensure a readable banner.

KEY PRINCIPLE

at work

SAY IT WITH PROPS: If it’s worth saying, it’s worth saying loudly! If it’s worth doing, it’s worth doing boldly! What better way to put your message out there, than to spell it out in twelve-foot-high letters?

OTHER PRINCIPLES AT WORK:

Take risks, but take care

Reframe

Everyone has balls/ovaries of steel

Do the media’s work for them

show, don’t tell

Make your actions both concrete and communicative

Related:

TACTICS

Guerrilla projection

Giant props web

Media-jacking

Détournement/Culture jamming

THEORIES

Points of intervention

Ethical spectacle

Framing web

CASE STUDIES

Battle in Seattle

PRACTITIONERS

Ruckus Society

GreeGreenpeace

Rainforest Action Network

FURTHER INSIGHT

The Ruckus Society, “Balloon Banner Manual”

http://ruckus.org/article.php?id=364

Tree Climbing

http://treeclimbing.coe.cornell.edu/content/resources

Destructables, “Banner Drops”

http://Destructables.org/node/56

Destructables, “Banner Hoist”

http://Destructables.org/node/57

Steal This Wiki, “Banners”

http://wiki.stealthiswiki.org/wiki/Banners

Freeway Blogger

http://freewayblogger.blogspot.com/

Blockade

Joshua Kahn Russell

COMMON USES

To physically shut down something bad (a coal mine, the World Trade Organization); to protect something good (a forest, someone’s home); or to make a symbolic statement, such as encircling a target (the White House).

Blockades commonly have one of two purposes: first, to stop the bad guys, usually by targeting a point of decision (a board-room), a point of production (a bank), or a point of destruction (a clearcut) see THEORY: Points of intervention; or second, to protect public or common space such as a building occupation or an encampment.

Blockades can consist of soft blockades (human barricades, such as forming a line and linking arms) or hard blockades (usinggear such as chains, U-locks, lock-boxes, tripods or vehicles. Blockades can involve one person or thousands of people, and can be a stand-alone tactic or an element of a larger tactic like an occupation.

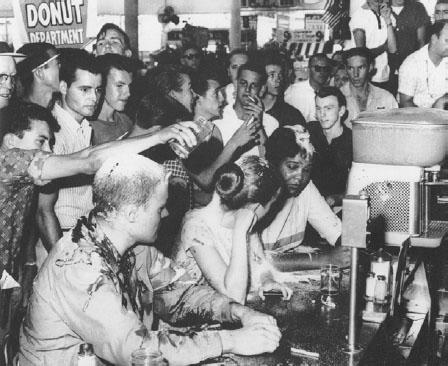

Daguerreotype entitled, “Barricades avant l’attaque, Rue Saint-Maur” (“Barricades Before the Attack, Rue Saint- Maur”). Barricades were a completely new tactic at the time, and spread like wildfire across Europe. This is one of the very first photos ever taken of a street protest. By M. Thibault.

Successful blockades can be primarily concrete or communicative see PRINCIPLE: Make your actions both concrete and communicative. Either way, all participants should be clear on the goals. For example, if your blockade is symbolic, it does not require a decision dilemma see: PRINCIPLE: Put your target in a decision dilemma. If, however, you have an concrete goal, like preventing people from entering a building, you must ensure that your blockade has the capacity to achieve that goal. In other words, make sure you’ve got all the exits covered.

Whatever the case, it’s important to lead with your goals. Don’t think in terms of less or more radical; think in terms of what is appropriate to your goals, strategy, tone, message, risk, and level of escalation see PRINCIPLE: Choose tactics that support your strategy.

Here are a few tips to keep in mind, adapted from the Ruckus Society’s how-to guide, A Tiny Blockades Book:

Build a crew. It all begins with a good action team and good nonviolence/direct-action training.

All roles are important. A good support team is essential.

Know your limits. Make a realistic assessment of your capacity and resources.

Scout, scout, scout. Spend a lot of time getting to know your location.

Know your choke points. These are the spots that make you the most secure and pesky blockader. Choose a spot that your target cannot just work, walk, or drive around.

Practice, and prepare contingency plans.

Don’t plan* for your action; plan through *your action. Think of the action as “the middle,” and expect a ton of prep work and follow-through — legal, emotional and political.

Have a media strategy. Make sure your message gets out and your action logic is as transparent as possible see THEORY: Action logic. Don’t let communications be an afterthought.

Eliminate unnecessary risk. Make your action as safe as it can be to achieve your goals see PRINCIPLE: Take risks, but take care.

Do not ignore power dynamics within your group or between you and your target. Race, class, gender identity (real or perceived), sexual identity (real or perceived), age, physical ability, appearance, immigration status and nationality all affect your relationship to the action.

Dress for success. Make sure that your appearance helps carry the tone you want to set for your action. Dress comfortably. Ensure that support people bring water, food, and extra layers.

Be creative. Have fun.

POTENTIAL PITFALLS: A complex and confrontational tactic like blockade requires meticulous planning and preparation, and should never be attempted without significant preparation, research and training see PRINCIPLE: Take risks, but take care.

KEY PRINCIPLE

at work

PUT YOUR TARGET IN A DECISION DILEMMA: When employing a blockade with a concrete goal, your ability to “hold the space” will depend on your decision dilemma. If you are able to prevent your target from “going out the back door” (metaphorically or literally), you have successfully created a dynamic where you cannot be ignored.

OTHER PRINCIPLES AT WORK:

Take risks, but take care

Choose tactics that support your strategy

Make your actions both concrete and communicative

Put your target in a decision dilemma

Escalate strategically

Maintain nonviolent discipline

Show, don’t tell

Take leadership from the most impacted

Anger works best when you have the moral high ground

Related:

TACTICS

Direct action

Banner drop

Mass street action

Occupation

THEORIES

Points of intervention

Pillars of support

Action logic

The commons

Cycles of social movements web

CASE STUDIES

Battle in Seattle

PRACTITIONERS

Grassy Narrows First Nation

Penan of Borneo

Civil rights movement

Global justice movement

Greenpeace

Migrant/immigrant rights movement

American Indian Movement

Black Panther Party

FURTHER INSIGHT

The Ruckus Society, “Manuals and Checklists”

http://ruckus.org/section.php?id=82

Praxis Makes Perfect, “Resources for Organizers”

http://trb.la/yTYBj7

The Ruckus Society, A Tiny Blockades Book pamphlet , Oakland California, 2005

Creative disruption

Nancy L. Mancias

COMMON USES

To expose and disrupt the public relations efforts of the armed and dangerous. Particularly useful at speeches, hearings, meetings, fundraisers and the like.

“Human salvation lies in the hands of the creatively maladjusted.”

—Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

If a war criminal like Dick Cheney or a corporate criminal like former BP CEO Tony Hayward comes to town, what’s the best way to challenge the spin they’ll put on their misdeeds? Often, the scale of the misdeeds and the imbalance of power are so great that activists will forgo dialogue and move straight to disruption, attempting to shut down or seriously disrupt the event. Disruption can be an effective tactic, and has been used successfully by small groups of people, often with little advance notice or advance planning.

“A well-designed

creative disruption

should leave

your target no

good option.”

The problem, of course, is that not only does the target control the mic, the stage, and the venue, but even more importantly, as an invited guest or the official speaker, s/he has the audience’s sympathy. A poorly thought-out shout-down or disruption can easily backfire. The target can portray themselves as a victim of anti-free speech harassment, thus gaining public sympathy and a larger platform. The challenge is to disrupt the event without handing your target that opportunity.

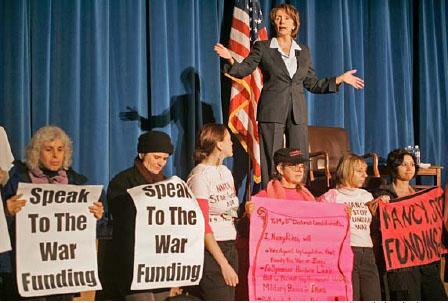

Sometimes an oblique intervention that re-frames the target’s remarks or forces a response to your issues without literally preventing anyone from speaking can be more effective than just shouting down someone. When House Speaker Nancy Pelosi held a rare town hall meeting in San Francisco in 2006 during the height of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, CODEPINK demonstrators — angry that Pelosi was not pushing for a cut-off in war funding — waited until the Q and A session, then surrounded the stage with their “Stop Funding War” banners and stood there, silently, for the remainder of the meeting.

The creative use of a sign or banner can help you avoid the “it’s an attack on free speech” trap. In effect, you’re adding an additional “layer” of speech; you’re engaging in more free speech, not less. Song can can also be used in this way. A 2011 foreclosure auction in Brooklyn, for instance, was movingly disrupted by protesters breaking into song. Song creates sympathy.

A creative disruption needn’t be passive. When Newt Gingrich came to the Minnesota Family Council conference for a book signing, a queer activist dutifully waited in line and when it came to his turn, dumped rainbow glitter over Gingrich, shouting, “Feel the rainbow, Newt! Stop the hate, stop antigay policies” as he was escorted out of the room. The video documenting the event see PRINCIPLE: Do the media’s work for them went viral and the disruption gained international press attention, sparking a wave of LGBT activism. The tactic of “glitter-bombing” even made it into an episode of the TV show Glee.

Theater is another way to “disrupt without disrupting.” When Jeane Kirkpatrick (Reagan’s Ambassador to the UN), came to UC Berkeley in the 1980’s, activists staged a mock death-squad kidnapping. “Soldiers” (students) in irregular fatigues marched down the main aisle barking orders in Spanish and dragged off a few students kicking and screaming from the audience. Others then scattered leaflets detailing the U.S.’s and Kirkpatrick’s support for El Salvador’s death-squad government from the balcony onto the stunned audience.

CODEPINK activists re frame a Nancy Pelosi speech at a town hall forum in 2006 with their silent protest — showing how creative disruption can be an effective tactic by putting their target in a lose-lose situation. Chronicle / Michael Macor.

As these examples show, it’s critical to tailor your disruption to the specific target and situation. Often, you can be more effective if you step out of the “combative speech box” and consider alternate modalities, like visuals, song, theater, and humor.

Republican Presidential candidate Rick Santorum being glitter-bombed at a Town Hall forum in late 2012 by LGBT rights activists. Not only did the initial hit of glitter creatively disrupt his meet-and-greet, but the continual presence of glitter on his person put him and his homophobic and anti-LGBT sentiments in a decision-dilemma. REUTERS/Sarah Conard

KEY PRINCIPLE

at work

PUT YOUR TARGET IN A DECISION DILEMMA: Well-designed creative disruption should leave your target no good option. If Nancy Pelosi had acknowledged or engaged with the protesters, she would have only elevated their credibility and drawn further attention to their message. Had security cleared out the silent activists, it would have looked heavy-handed. Had she left the scene, it would have been seen as a capitulation. Her least worst option, and what she chose to do, was continue with the event — whose meaning was then reframed by the silent protest signs around her. A well-designed creative disruption puts you in a win-win — and your target in a lose-lose — situation.

OTHER PRINCIPLES AT WORK:

The real action is your target’s reaction web

Kill them with kindness

Show, don’t tell

Reframe

Think narratively

*Play to the audience that isn’t there

Do the media’s work for them

Related:

TACTICS

Infiltration

Public filibuster

Flash mob

Eviction blockade

Sit-in web

Direct action

Guerrilla theater

THEORIES

Action logic

Ethical spectacle

Points of intervention

Alienation effect

CASE STUDIES

Public Option Annie

Whose tea party?

Colbert roasts Bush

Bidder 70

Citizens’ Posse

PRACTITIONERS

CODEPINK Women for Peace

WAG

FURTHER INSIGHT

Thompson, Nato, and Gregory Sholette. The Interventionists: Users’ Manual for the Creative Disruption of Everyday Life. North Adams, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, 2004.

Video: “Newt Gingrich Gets Glittered at the Minnesota Family Council”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g8OZsJokBB0

Video: “Auctioneer: Stop All the Sales Right Now!”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u3X89iViAlw

Video: “Mass Walkout at Wayne State Leaves IDF Spokesman Lecturing to Empty Room”

http://trb.la/yWfBd8

Creative petition delivery

Duncan Meisel, with help from Pascal Vollenweider @ Avaaz

COMMON USES

To translate online outcry into offline action; to make mass public opposition unavoidably visible to a campaign target.

Online petitions are an effective way of spreading information, raising an outcry or putting pressure on a target. But online actions alone are easily ignored by targets. To translate virtual signatures into real-world action, a number of netroots organizations have developed the art of creative petition delivery. While publicizing your message and the support it has garnered, creative petition deliveries put public pressure on your target.

It’s helpful to find creative ways to physically quantify the number of petition signatures. A number of well-labeled boxes rolled into a target’s office is a tried and true approach, but other tactics can be effective as well. For a petition asking the World Health Organization to investigate and regulate factory farms, the international multi-issue campaign organization Avaaz set up 200 cardboard pigs — each representing 1,000 petition signers — in front of the WHO building in Geneva, providing the media with a visual hook on which to peg stories about factory farms and swine flu.

But you don’t have to physically occupy the same space as your target. Attracting media attention can be an effective way to reach a target as well. Avaaz sometimes places ads in newspapers that both their target and supporters are likely to read. In one instance, to deliver a petition against nuclear energy to German Chancellor Andrea Merkel, they purchased an ad in Der Spiegel, the German paper of record.

Or try a more outlandish media stunt. To deliver a petition against deepwater oil drilling in the Arctic, Greenpeace International sent its executive director to a controversial oil rig in the middle of the ocean, where he trespassed onto the rig to deliver the petition to the ship’s captain — at which point he was arrested and held for four days. Between the unusual way it was delivered and the media coverage that resulted, the petition was difficult for the target to ignore.

Sometimes less public tactics can be equally effective: to deliver a petition about cluster bombs to a UN conference debating arms munitions treaties, Avaaz first digitally delivered 600,000 petition signatures to the head of the conference, and then quietly distributed 1,000 fliers to conference attendees, describing the issue and listing the number of people who’d signed the petition. Even the subtle hint of public pressure created a stir in the often obscure world of UN diplomats. The delivery had a big impact on the eventual outcome of the conference, which did not adopt a draft treaty to allow stockpiling of cluster bombs.

Creative petition deliveries allow organizers to turn online outcry into offline action. By becoming unavoidably visible to a campaign target, creative deliveries make sure the voices of thousands of petition signers are publicly heard.

KEY PRINCIPLE

at work

MAKE THE INVISIBLE VISIBLE: Creative petition deliveries give an abstract issue a physical and visual presence. Public figures and decision-makers can afford to avoid listening to public outcry as long as it remains distant and exclusively online. By bringing the voices of petition signers to a target (and the media) in a way that makes them impossible to ignore, creative petition deliveries amplify the effectiveness of online organizing efforts.

OTHER PRINCIPLES AT WORK:

Create online-offline synergy web

Show, don’t tell

Bring the issue home

Consider your audience

Choose your target wisely

Put your target in a decision dilemma

Play to the audience that isn’t there

Related:

TACTICS

Distributed action

Artistic vigil

Advanced leafleting

THEORIES

Action logic

Points of intervention

Ethical spectacle

PRACTITIONERS

Avaaz.org

MoveOn.org

Greenpeace

FURTHER INSIGHT

Creative Petition: Bags of Grain to the White House to Prevent War, 1955

http://trb.la/wceMpx

Avaaz, “Highlights”

http://www.avaaz.org/en/highlights.php

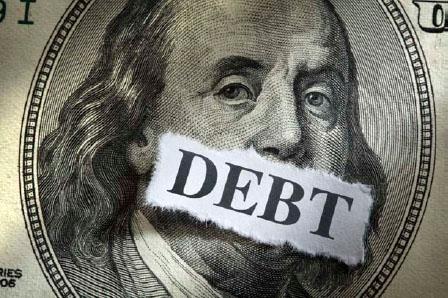

Debt strike

Sarah Jaffe

Matthew Skomarovsky

COMMON USES

To fight back against financial exploitation when many people are crushed by debt.

“If you owe the bank $100,that’s your problem; if you owe the bank $100 million, that’s the bank’s problem.”

—John Paul Getty

What does non-cooperation with our own oppression look like? Sometimes it looks like Rosa Parks refusing to sit in the back of the bus, and sometimes it’s less visible — for instance, a coordinated refusal to make our monthly debt payments.

With wages in many countries stagnant since the 1970s, people have increasingly turned to debt financing to pay for education, housing and health care. Banks have aggressively pursued and profited from this explosion of debt, fueling economic inequality, inflating a massive credit bubble and trapping millions in a form of indentured servitude.

Most people feel obliged to pay back loans no matter the cost, or fear the lasting consequences of default, but the financial crisis has begun to change that. After watching the government shovel trillions in bailouts and dirt-cheap loans to big banks, growing numbers view our debt burdens as a structural problem and a massive scam rather than a personal failure or a legitimate obligation. But asking politicians and banks for forgiveness is unlikely to get us anywhere, because our payments are their profits. What we need is leverage.

Enter the debt strike, an experiment in collective bargaining for debtors. The idea is simple: en masse, we stop paying our bills to the banks until they negotiate. Because they can’t operate without these payments — for student loans, mortgages, or consumer credit — they’re under severe pressure to negotiate. Such a strike can be connected to demands to reform the financial system, abolish predatory and usurious loan conditions, or provide direct debt forgiveness. Strikers could even pool some or all of the money they’re not paying, and put it into a “strike fund” to support the campaign or kick-start alternative community-based credit systems.

Coordination is key. We can’t act in isolation, exposing ourselves to retaliation and division. Instead, participants should all sign a pledge — either public or confidential — to stop paying certain bills. When enough people sign up to provide real leverage, strike. In the meantime, organize furiously, publicize a running total, aggregate grievances, collect outrageous debt stories, and watch the financial élite panic.

A debt strike is audacious, simple, and easy to participate in — easier than paying bills, since all you have to do is not pay your bills. It takes courage and social support, but provides immediate gratification. Who doesn’t despise the monthly ritual of sending away precious cash to line the pockets of dishonest and destructive financial institutions?

Although a massive debt strike has not yet been organized, efforts are underway. People have been mobilizing for years to fight foreclosures and predatory loans. The Occupy Student Debt Campaign aims to gather a million student debt refusal pledges. Another group is building a social pledge system to connect debtors by neighborhood, common lenders and demands. Online social networks, pledge-to-act platforms like ThePoint.com and story aggregators like Tumblr may soon become weapons on the battlefield of debt.

The outrage, organizers, techniques and tools already exist, and the tactic has perhaps never been more justified. The debt strike is out there, waiting to take the world by storm.

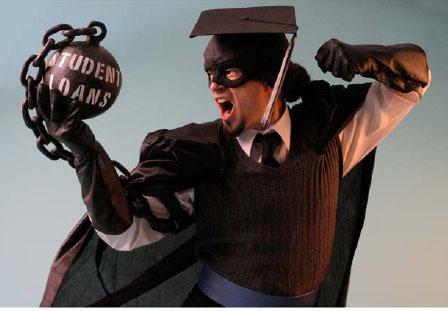

Gan Golan as the Master of Degrees. From the book The Adventures of Unemployed Man by Gan Golan and Erich Origen. Photo by Friedel Fisher.

POTENTIAL PITFALLS: While the initial sign-up is as easy as signing an online petition, unlike a petition, there are potentially serious consequences. Defaulting on a loan impacts your credit rating,which can severely impact your future ability to get a credit card,rent an apartment,buy a car,or even get a job. Thus a successful debt strike will require support networks for strikers, the same way a union has a strike fund to support striking workers.

“A debt strike is

easier than paying

bills, since all you

have to do is not

pay your bills.”

Achieving the critical mass required for the tactic to be effective may also be a challenge. A debt strike is only effective at large scale.

KEY THEORY

at work

DEBT REVOLT: Debt is too often treated like a personal failing that shouldn’t be discussed in public, rather than a common struggle against systemic exploitation. We also tend to think of debt as a non-negotiable fact rather than a social construct. Once we realize that debts are shared fictions that can be renegotiated or even rejected entirely, we discover we have the power to pull the plug on a system that relies on our separation, shame, and consent. Household debt in the U.S. is around ninety percent of GDP, has grown at nearly twice the rate of real incomes, and as Mike Konczal has noted, impacts the bottom 99% disproportionately. As the slogan for the Occupy Student Debt campaign says: “Can’t Pay? Won’t Pay? Don’t Pay!”

OTHER THEORIES AT WORK:

Pillars of Support

Points of intervention

Captitalism

The commons

Student protester. Lack of economic opportunity is a threat to students, but what will non-cooperation with their oppression look like, and who will it threaten?

Related:

TACTICS

General Strike

Distributed Action

Direct Action

PRINCIPLES

Debtors of the world, unite!

Choose your target wisely

Escalate strategically

Use your radical fringe to slide the Overton window

*Take risks but take care

Take leadership from the most impacted

Put your target in a decision dilemma

FURTHER INSIGHT

Stephen Lerner, “Take the Fight to the Streets,” April 18, 2011

http://trb.la/wooXp3

Sarah Jaffe, “Debtor’s Revolution: Are Debt Strikes Another Possible Tactic in the Fight Against the Big Banks?” AlterNet, November 3, 2011

http://trb.la/wIMxqX

Rortybomb, “Some Quick Thoughts on the Notion of a Debtors’ Strike”

http://trb.la/ydZE6e

Occupy Student Debt Campaign

Debt Strike kick-stopper

http://forum.contactcon.com/discussion/33/kick-stopper#Item_1

Détournement

Zack Malitz

COMMON USES

Altering the meaning of a target’s messaging or brand; packaging critical messages as highly contagious media viruses.

Urban living involves a daily onslaught of advertisements, corporate art, and mass-mediated popular culture see THEORY: Society of the spectacle. As oppressive and alienating as this spectacle may be, its very ubiquity offers plentiful opportunities for semiotic jiu-jitsu and creative disruption. Subversive and marginalized ideas can spread contagiously by reappropriating artifacts drawn from popular media and injecting them with radical connotations.

“Détournement

appropriates and

alters an existing

media artifact, one

that the intended

audience is already

familiar with, in

order to give it a

new meaning.”

This technique is known as détournement. Popularized by Guy Debord and the Situationists, the term is borrowed from French and roughly translates to “overturning” or “derailment.” Détournement appropriates and alters an existing media artifact, one that the intended audience is already familiar with, in order to give it a new, subversive meaning.

In many cases, the intent is to criticize the appropriated artifact. For instance, the neo-Situationist magazine Adbusters has created American flags bearing corporate logos in place of stars. The traditional flag, which is often used to quash dissent by equating America with liberty and progress see THEORY: Floating signifier, is made to communicate its own critique: corporations, not the people, rule America. Similarly, an Adbusters “subvertisement” for Camel cigarettes, perfectly rendered in the style and lettering of real Camel advertisements, depicts a bald Joe Chemo in a hospital bed.

Détournement works because humans are creatures of habit who think in images, feel our way through life, and often rely on familiarity and comfort as the final arbiters of truth see PRINCIPLE: Think narratively. Rational arguments and earnest appeals to morality may prove less effective than a carefully planned détournement that bypasses the audience’s mental filters by mimicking familiar cultural symbols, then disrupting them.

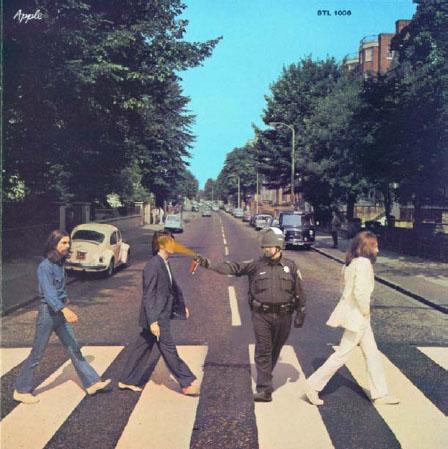

“Pepper spray cop” Lt. Pike strolls through the Beatles’ iconic Abbey Road cover, casually pepper spraying Paul McCartney. This doctored image plays on the popularity of the Beatles to emphasize the callous absurdity of Pike’s actions.

For instance, UC Davis police officer Lt. John Pike began to pop up in some unexpected places after he was captured on film casually pepper spraying students during a peaceful protest. One image depicted Lt. Pike walking through John Trumbull’s classic painting The Declaration of Independence and pepper spraying America’s founding document, while another depicted him in Georges Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, pepper spraying a woman lounging in the grass. These images, and other détournements of “pepper spray cop,” are some of the most visible critiques of police brutality in recent American history.[3]

In addition to its instrumental, critical function, détournement has an important humanistic function. Détournement can be used to disrupt the flow of the media spectacle and, ultimately, to rob it of its power. Advertisements start to feel less like battering rams of consumerism and more like the raw materials for art and critical reflection. Advertising firms may still generate much of culture’s raw content, but through détournement and related culture jamming tactics, we can reclaim a bit of autonomy from the mass-mediated hall of mirrors that we live in, and find artful ways to talk back to the spectacle and use its artifacts to amplify our own voices.

POTENTIAL PITFALLS: Détournement is just a tactic, and like any tactic, it needs to be integrated into a larger strategy to be effective see PRINCIPLE: Choose tactics that support your strategy. While détournement can be a highly effective political tool, when divorced from a larger strategy, it can slide into a tool of complacency or complicity in the guise of resistance. There’s nothing wrong with taking savage pleasure in subverting grossly offensive media images, but take care to avoid using détournement as merely a palliative or a substitute for organizing.

KEY PRINCIPLE

at work

KNOW YOUR CULTURAL TERRAIN: As an act of semiotic sabotage, détournement requires the user to have fluency in the signs and symbols of contemporary culture. The better you know a culture, the easier it is to shift, repurpose, or disrupt it. To be successful, the media artifact chosen for détournement must be recognizable to its intended audience. Further, the saboteur must be familiar with the subtleties of the artifact’s original meaning in order to effectively create a new, critical meaning.

OTHER PRINCIPLES AT WORK:

Show, don’t tell

Make the invisible visible

Reframe

Brand or be branded

Balance art and message

Don’t just brainstorm, artstorm!

Use others’ prejudices against them

This altered iconic image undercuts Coca Cola’s brand by evoking the company’s violent labor-repression strategies.

Related:

TACTICS

Media-jacking

Identity correction

Guerrilla projection

Guerrilla newspaper web

THEORIES

Society of the spectacle

Ethical spectacle

Memes

Alienation effect

Floating signifier

Points of intervention

CASE STUDIES

Billionaires for Bush

Colbert roasts Bush

Mining the Museum

Couple in the Cage

The Barbie Liberation Organization

99% bat signal

PRACTITIONERS

The Situationist International

Adbusters

Jon Stewart

Stephen Colbert

Center for Tactical Magic

Robbie Conal

Guillermo Gómez-Peña

Gran Fury

Guerrilla Girls

Preemptive Media

Reverend Billy and the

Church of Earthalujah

FURTHER INSIGHT

“A User’s Guide to Détournement”

http://trb.la/zvA2dH

“Détournement as Negation and Prelude”

http://trb.la/zTgoFp

Mark Dery, “Culture Jamming: Hacking, Slashing, and Sniping in the Empire of Signs”

http://markdery.com/?page_id=154

Lasn, Kalle. Culture Jam: The Uncooling of America. New York: Eagle Brook, 1999.

Heath, Joseph, and Andrew Potter. The Rebel Sell: Why the Culture Can’t Be Jammed. New York: Harper, 2005.

Destructables, “The Art and Science of Billboard Improvement”

http://destructables.org/node/82

Destructables, “Phonebooth Takeover Tutorial”

http://destructables.org/node/52

Destructables, “Shop-Dropping Product Lables”

http://trb.la/wLEUjZ

Direct action

Joshua Kahn Russell

COMMON USES

To shut things down; to open things up; to pressure a target; to re-imagine what’s possible; to intervene in a system; to empower people; to defend something good; to shine a spotlight on something bad.

“Direct action gets the goods.”

—Industrial Workers of the World

Direct action is at the heart of all human advancement. Sound like a grandiose claim? It is. But it’s also beautifully simple: direct action means that we take collective action to change our circumstances, without handing our power to a middle-person.

Direct action is a physical act that should be designed so that the story tells its self. It seeks to change power dynamics directly, rather than relying on others to make changes for us.

We see instances of direct action in indigenous parables and stories, in the Bible, Torah and Koran, in every people’s movement and popular revolution in modern history. Direct action is often practiced by people who have few resources, seeking to liberate themselves from an injustice.

People often conflate direct action with “getting arrested.” While sometimes getting arrested can amplify your message, or is strategically necessary to achieve your goal, it isn’t the point of direct action. (In most liberation struggles throughout history, “getting captured” is actually seen as a bad thing!)

Similarly, people often conflate direct action with civil disobedience. Civil disobedience is a specific form of direct action that involves intentionally violating a law because that law is unjust — for instance, refusing to pay taxes that would fund a war, or refusing to comply with anti-immigrant legislation. In these circumstances, breaking the law is the purpose. With other kinds of direct action, laws may be broken, but the law being broken isn’t the point. For example, we may be guilty of trespassing if we drop a banner from a building, but the violation is incidental: we aren’t there to protest trespassing laws.

While associated with confrontation, direct action at its core is about power. Smart direct action assesses power dynamics and finds a way to shift them.

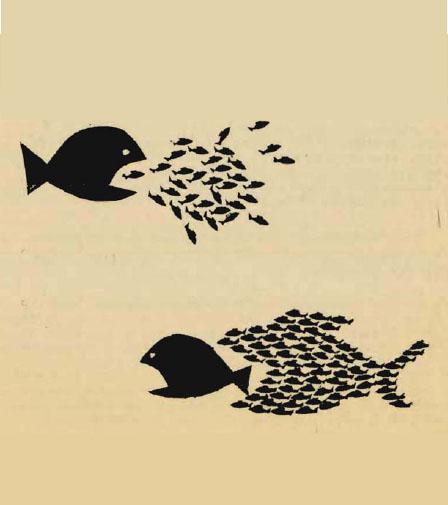

One way of thinking about power is that there are two kinds: organized money and organized people. We don’t have billions of dollars to buy politicians and governments, but with direct action organized people spend a different currency: we leverage risk. We leverage our freedom, our comfort, our privilege or our safety.

“Rather than

deferring to others,

we seek to change

the dynamics of

power directly”

As Frederick Douglass said, “power concedes nothing without a demand.” Malcolm X elaborated, “Power never takes a step back, except in the face of more power.” Rather than deferring to others to make changes for us through votes or lobbying, we seek to change the dynamics of power directly.

Direct action is often practiced by people who have few resources, seeking to liberate themselves from an injustice. Image by Black Mesa Indigenous Support (BMIS) Collective.

POTENTIAL PITFALLS: Direct action involves significant levels of risk for all involved. It is imperative to be careful, conscious and deliberate about the risks you take. A good action planner distinguishes between the risks she can (and should) minimize, and the ones she cannot, and will explain to all participants the potential consequences see PRINCIPLE: Take risks, but take care.

KEY THEORY

at work

ACTION LOGIC: Because direct action is a physical act, it often speaks louder and deeper than anything you might say or write. Ideally, you should choose your target and design your action so that the action itself tells the story.

OTHER THEORIES AT WORK:

Points of intervention

Pillars of support

Hamoq & hamas

Revolutionary nonviolence

Related:

TACTICS

Occupation

Blockade

Eviction blockade

General strike

Mass street action

Prefigurative intervention

Nonviolent search and seizure

PRINCIPLES

Take risks but take care

Choose your target wisely

Choose tactics that support your strategy

Maintain nonviolent discipline

Put your target in a decision dilemma

Escalate strategically

If protest is made illegal, make daily life a protest

Take leadership from the most impacted

Turn the tables

We are all leaders

Don’t dress like a protester

Shift the spectrum of allies

CASE STUDIES

The salt march

Battle in Seattle

Occupy Wall Street web

Justice for Janitors

Turning streets into gardens

Bidder 70

Reclaim the streets

Daycare center sit-in

PRACTITIONERS

The Ruckus Society

Civil rights movement

Gandhi

Antiwar movement

Quakers

Unions

Jesus of Nazareth

American Indian Movement

Jewish resistance during the Holocaust

The Boston Tea Party (original)

Global justice movement

Anti-nuclear movement

Rastafarianism

GI resistance

Immigrant rights

Earth First

ACT-UP

Mitch Snyder

FURTHER INSIGHT

Praxis Makes Perfect — Direct Action resources

http://trb.la/Awdjso

Gene Sharp’s 198 methods of nonviolent action

http://trb.la/yNUMG2

Video, Book and Interactive Game on Direct Action: A Force More Powerful

http://www.aforcemorepowerful.org/

War Resisters’ International handbook for nonviolent campaigns

http://wri-irg.org/node/3855

Alliance of Community Trainers

http://www.trainersalliance.org/

Ruckus Society

http://www.ruckus.org

RANT Collective

http://www.rantcollective.net

Destructables, “Lockboxes”

http://destructables.org/node/59

Distributed action

Phil Aroneanu

COMMON USES

To demonstrate the breadth, diversity and power of a movement; to swarm a large target in diverse locations.

We use the Internet for news, to be social, and to share information, but it can also be a radical tool for connecting people around the world in service to a common cause. That might mean signing your name to a petition, but it can also involve taking real world action in our own towns and cities. At its best, a distributed action projects the power of the movement and gives activists a sense of being part of a greater whole. This is a particularly useful tactic when a movement is young, dispersed, and minimally networked.

“A distributed action

projects the power

of the movement

and gives activists

a sense of being

part of a greater

whole.”

There are a number of ways that distributed action can help propel a campaign forward and bring a critical issue to the fore, but here are a few key elements:

The day of action. A group of people create a call to action, and provide a meme see THEORY, message, or framework for others around the world to take similar action at the same time. The fact that the events all happen at the same time projects a sense of power and focuses attention on the issue at hand. Days (or weeks) of action can be highly disciplined and structured, or they can be more like a potluck dinner, where everybody brings the dish s/he feels like cooking up. Organizers might choose to invest time and energy in select “flag-ship” locations to help drive the story and take things to a higher level in a few spots.

The call to action. A call to action should resonate not just with your core supporters and networks, but should tell a story that the general public will understand, and motivate new volunteer leaders to take to the streets. Depending on the situation, a call to action might have an embedded demand of political leaders, or it can simply be an expression of grievances, like the call to #occupywallstreet.

Providing the tools. Hard work, a compelling story, and a healthy dose of inspiration are the most important elements of a successful distributed action. But it can be helpful to provide some extra resources for those activists who have never organized an action before. This can be as simple as posting a web link to a few tips, or as complex as offering in-person trainings and downloadable toolkits with posters, checklists, sample press releases and more. Some kinds of actions, especially those that involve nonviolent direct action, will require more support than others see PRINCIPLE: Take risks, but take care.

POTENTIAL PITFALLS: By its nature a distributed action is risky. Not physically, but politically: You put out a call, and people you’ve never met respond and roll into action under your banner. Some folks may go way off message or do something foolish that requires you to engage in damage control. This is part of the risk using a tactic with such an open architecture, but should not discourage you from doing it. Most things will probably go swimmingly, but the more you follow the guidelines above — a strong framework, clear call to action, and solid tools to help folks stay on track — the less likely you are to have problems. Many groups also use nonviolence guidelines or a code of conduct that people agree to abide by when signing up online.

KEY PRINCIPLE

at work

HOPE IS A MUSCLE: A successful distributed action demands commitment from all involved. It’s easy to feel like nobody is listening. Distributed action runs on inspiration, momentum, hope and hard work. If you tell a story that resonates, pour your utmost efforts into empowering others to take action, and keep a positive and fun outlook, you can pull off a great and successful distributed action.

OTHER PRINCIPLES AT WORK:

Simple rules can have grand results]]

*Make new folks welcome

Enable, don’t command

Create levels of participation web

Delegate

Choose tactics that support your strategy

Stay on message

Use the Jedi mind trick

This ain’t the Sistene Chapel

Do the media’s work for them

Consider your audience

Related:

TACTICS

Flash mob

Prefigurative intervention

Human banner

Debt strike

Artistic vigil

THEORIES

Memes

Floating signifier

Hashtag politics

Points of intervention

The tactics of everyday life

The social cure

CASE STUDIES

Lysistrata project

Stolen Beauty boycott campaign

Billionaires for Bush

Occupy Wall Street web

Reclaim the Streets

Yomango

PRACTITIONERS

Billionaires for Bush

UK Uncut

FURTHER INSIGHT

International Solidarity work as Distributed Action for South Africa:

http://trb.la/xIwDYd

World AIDS Day Distributed Actions:

http://www.worldaidsday.org/

350.org, “International Day of Climate Action” (2009)

http://www.350.org/en/october24

Billionaires for Bush, “Do-It-Yourself Manual” (2004)

http://trb.la/wEe81W

Electoral guerrilla theater

L. M. Bogad

COMMON USES

Running for public office as a creative prank — not to win the election, but to get attention for a radical critique of policy or to sabotage the campaign of a particularly heinous candidate

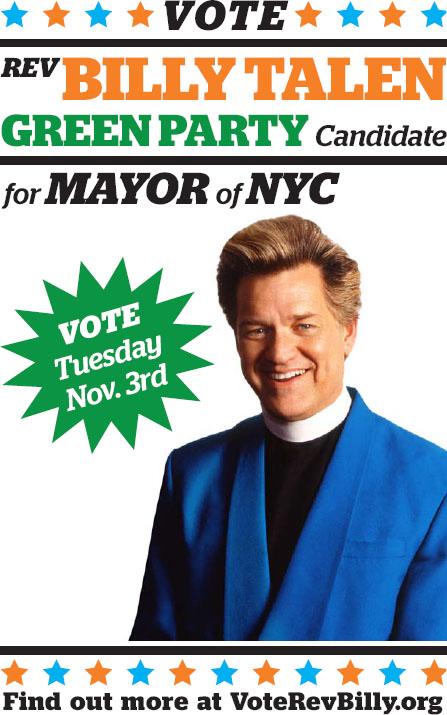

A group of eco-anarchist “gnomes” running for city council in Amsterdam; Reverend Billy, an anti-consumerist performance artist, running for mayor of New York City; a drag queen running for the Australian senate as the queer dopplegänger of far-right racist politician Pauline Hanson. These are all examples of electoral guerrilla theater, in which creative activists run for public office to inspire critique of the electoral system or the choices on offer.

The term electoral guerrilla yokes two seemingly incompatible approaches. Electoral activists work within the state’s most accepted and conventional avenues in an attempt to reform the system peacefully. Guerrillas, in the military sense, exist on the extreme margins of the social system, constantly on the move, launching surprise attacks against the state before disappearing again. This contradiction is what makes electoral guerrilla theater a wild card in the repertoire of resistance, both for the target and the activist. It is an unstable and problematic combination that can take all players involved by surprise.

“The power of the

electoral guerrilla

is in great part the

fact that you

are not trying to

win state power

but to call its

core premises

into question.”

Winning is rarely the goal. However, by piggybacking on the massive media attention that elections gather, a clever guerrilla campaign can attract much more public attention than might otherwise be possible. Craft a compelling and funny character that fits your critique, say, a pro-corporate pirate who wants to get in on the easy plunder that Wall Street has been enjoying, for example. Craft your persona, and start crashing mainstream political events — or make a scene when you are prevented from crashing. Even better, earn more scandalous attention by crashing your absurdity through the front door of the power structure by getting a slot in an “equal time” debate, or getting on the ballot with your silly character name, or getting interviewed by the straight media in character.

Couple things to keep in mind:

Do what they do but with a critical difference see THEORY: Alienation effect. If you’re doing this right, by absurdly aping the clichés of the “proper” candidates you can call attention to the fact that they are just as socially-constructed and fake as your pirate/gnome/witch/etc. Cut ribbons. Kiss babies. Bring out the empty symbolism of these rituals, and insert your own radical critique, alternative meanings to them with a few quick jokes.