Beverley Skeggs, Sara R. Farris, Alberto Toscano & Svenja Bromberg

The SAGE Handbook of Marxism

Which Handbook for What Marxism?

Without Guarantees, Without Apologies: Remaking Marxism for the Twenty-First Century

Part I Reworking the Critique of Political Economy

Later Marxists: The Retreat into Reticence

Reinstating Merchant Capitalism

A broad taxonomy of merchant capitalism

Problems, Conceptual and Practical

Other Modes of Production: From Lineage to Slavery

Feudalism and the Tributary Mode of Production

The Value and Uses of the Concept of ‘Mode of Production'

3. Social Reproduction Feminisms

Margaret Benston on Paid and Unpaid Work

Wages for Housework and the Domestic Labour Debate

Lise Vogel and the Unitary Theory

Social Reproduction Feminist Strategies

From Life-Making to World-Making: SRT and the Climate Crisis

Rent: Historical and Theoretical Considerations

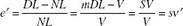

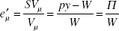

The Distinction between Profit and Rent: Theoretical Elements

The Hypothesis of the Becoming-Rent of Profit in Marx

Profit and Rent from Industrial to Cognitive Capitalism

The Hegemony of Profit over Rent in Fordism

The Capital–Labour Relation in Cognitive Capitalism

The Hegemony of Rent over Profit in Cognitive Capitalism

The Theory of Value and the Transformation Problem

Marx's (and Not Marxist) Theory of Value

Abstract Labour as the Social Substance of Value

Value-form, Money and the Fetish Character of the Commodity

Functions of Money in a Capitalist Economy

Contemporary Empirical Research and Controversies

Financialisation vs rate of profit as cause of stagnation and crisis

Marx's Discovery of Labour, or Conscious Life-Activity, as Humanity's ‘Species-Being'

Controversies Over Marx's Perspective on Human Labour

Introduction: Twenty-First-Century Automation

Marx and the Automatic Factory

Capitalist and Communist Uses of Machinery

The ‘Absolute Law’ of Automation

Automation, Capital Composition, and Crisis

‘Incomplete Subordination of Labor to Capital’ or, the Resistance to Automation

Unproductive Labor and the Crisis Tendency

The Inseparability of Form and Content: Why Marx Wrote Few Reflections on Method

Immanent Critique and Marx's Critical Social Epistemology

The 1857 Introduction to the Grundrisse: Six Key Points

Grasping Social Forms in Their Complexity

Method and Substance in Marx's Critique of Political Economy

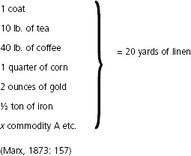

Value and its Necessary Form of Expression

Two Sore Points: Commodity Money and the ‘Transformation Problem'

Georg Lukács: Method as Marxist Orthodoxy

Galvano Della Volpe: Against the A Priori

Analytical Marxism: Analysis Without Phenomenology

Horkheimer and Adorno: From ‘Traditional and Critical Theory’ to the ‘Neue Marx Lektüre'

10. The Transformation Problem

Marx between ‘Value’ And ‘Labour'

The Transformation Problem and Exploitation

What Are We Talking About When We Talk About Exploitation?

Part II Forms of Domination, Subjects of Struggle

Historical Explanation and Class

Class, Gender and Heterosexuality

Political Economies of Punishment

Neo-Marxist Criminology and Late Capitalism

Racialized Social Structure and Penal Discipline in the USA

Beyond the Political Economy of Punishment?

Stuart Hall: Articulations of Race and Class

Cedric Robinson: Racial Capitalism and the Black Radical Challenge to Marxism

Angela Y. Davis: Black Feminism, Freedom and the Blues

From Capitalism and Slavery to Slavery and Freedom

Present and Future Explorations

Gender Relations in Marx and Early Marxists

Gender Relations and Class Society: on Friedrich Engels

Gender Relations as Relations of Production

Dual Sex/Gender Systems Analysis

Gender and Sexual Division of Labour Analysis

The Materiality of Gender Subjectivity

Gender and Sexuality as Consumption

Gender Subjectivity as a Classed Moral Formation

Part III Political Perspectives

Pre-Marxist Conceptions of Revolution

Marx and Engels Rediscover the Social Revolution

The Bourgeoisie and the Proletariat as Revolutionary Classes

Permanent Revolution: the Working Class in the Bourgeois Revolution

On the Historical Specificity of Capitalist States

The Conundrum of Separation and Alienation

How to Explain State Functions and Politics

Stages of Capitalism and Stages of Capitalist State Forms

On the Difference between States and State-Like Institutions

On Bourgeois and Non-Bourgeois Capitalist States

The Plurality of Capitalist States

20. Nationalism and the National Question

The National Question: Origins and Debates

The Nation-Form: Capital and the Nation

The Nation after Globalization

Theory, Belief, and Dialectics

Crisis Theory as a Theory of ‘Excess Capital Alongside Surplus Populations'

Narrating the Possibility of Crisis: The Exchange Process and the Law of Value

The ‘Deepest, Most Hidden Cause of Crisis': Political Economy's Unconscious

Narrating the Inevitability of Crisis: The Vicious Cycle of Accumulation

The Suspension of the Capital-Relation: Wealth and Poverty

Lazarus, the Industrial Reserve Army, and Repressive Force

Crisis and State Apparatuses: The Production of Difference

Crisis-as-Transition and the Theory of Imperialism

Imperialism, State Power, and Crisis: Borders and War

Interest-Bearing Capital: Time is Out of Joint!

Introduction: The Many Voices of Communism

Critique and Overcoming of Other Communisms

Communist Individualism, Communist Freedom

Conclusion: Communism and the Matter of Abolition

Part IV Philosophical Dimensions

6. The Crisis of Totality and Theories of Moments

6.3 Domestic Labour and the Subjugation of Gender

6.4 Imperialism and Racial Subjugation

Kant's Rehabilitation of Dialectics

The Young Marx and the Dialectic

Marx Returns to the Science of Logic

Dialectical Method and System in Marx and Engels

Labor Productivity and Time Compression

Space and Radical Political Traditions

Space as a Level of Social Totality

Political Economy and Urban Space

Origins of the Concept of Alienation in Political Economy and Social Contract Theory

Theological Origins of the Concept of Alienation

Alienation in Marx's 1844 Manuscripts: From Entäusserung to Entfremdung and Back

Alienation's Four Moments in the 1844 Manuscripts and beyond

Twentieth-Century Debates about Alienation, Labour, and Freedom

The Problematic Editorial History of the Theses on Feuerbach

Sensuous Activity? Idealism or Materialism?

Practical Alienation (Social Self-Estrangement)

Practice and Revolutionary Practice

Practice, Production and Labour

Some More Problematical Elaborations of ‘Fetishism'

31. Ideology-Critique and Ideology-Theory

Marx and Engels: Beyond a Critique of ‘False Consciousness'

Gramsci's Combination of Ideology-Critique and Theory of Hegemony

Beyond Althusser: Perspectives of a Critical-Structural Theory of Ideology

The Theoretical Formation of ‘Real Abstraction’ (1936–1970)

The Materialist Impetus: Sohn-Rethel's Early Conceptualisation

Intellectual and Manual Labour: Real Abstraction as the Praxis at the Origin of Thought

The Trajectory of Real Abstraction: Helmut Reichelt

Subsumption in Marx's Writings

Historical Reception and Debates

Periodisation and ‘Total’ Subsumption

Subsumption and the Critique of Political Economy

34. Primitive Accumulation, Globalization and Social Reproduction

Introduction: Rethinking Primitive Accumulation

Primitive Accumulation and the Restructuring of Social Reproduction in the Global Economy

Political Recomposition and Social Revolution

Archive and Present Use of the Term

In the Lands of Debt and Consumption

The Feminist reading of Extractivism

Agriculture and the Problem of Natural Limits in Political Economy

Critique of Metabolic Rift in Capital

Economic Crisis and Ecological Crisis

Natural Limit and Production of Nature

Introduction: From Thermodynamics to Marxism

Marx and Engels on Transformations of Energy and Value

A Half-Century Hiatus: Stalin's Ecology Versus Stanchinskii's

The Re-Birth of Energetics in Marxism and Marxism in Energetics: the Relation of Energy to Value

Neoliberalism and Climate Capitalism

Global Political Economy and Climate Change

Conclusion: From Capitalism to Class

Fragments of a(n Impossible) History

Conclusion: Materiality/Abstraction/Concreteness

Manfredo Tafuri and the Venice School

The critique of Ideology and Postmodernism in the 1980s USA

New Marxist Architectural History and Theory

Industries of Architecture Today

Culture and the Crisis of Marxism

The Soviet Theorists: Lukács, Voloshinov, Bakhtin

After Structuralism, beyond Freudo-Marxism

Classical Marxism in the Twenty-First Century

Some Foundations of Contemporary Marxist Approaches to Literature

Pathways in Marxist Literary Criticism

Coda: The Location of Anglophone Marxist literary Criticism

Poetics as a Modality of Political Organisation

Compulsive Communication of Social Media

Fragment, Rupture, and Anonymity in Comité

A Racist and Imperialist Genealogy

Marxists and the Problem of International Relations

International Relations (IR) and the Problem of Marxists

The World Outlook of the Bourgeoisie

Marxism and Legal Thought: An Absent Presence?

Law and the Structure of Capitalism

Debates in the Russian Revolution

Marxism: Official and Unofficial

European Marxism, ‘BritCrit’ and the Revival of Pashukanis

Standardisation, Dependency and Management: The Social Relations of the Factory

The Craft Worker, Dependency and Standardisation: Transforming Knowledge to Enable Valorisation

The Pursuit of Standardisation and the Managed Bureaucratic Organisational Form

Monopoly Capitalism and Management as Legitimate Knowledge

Conclusion: Management, Standardisation and Difference

Lefebvre, Althusser and the End of Philosophy

Marx's Method as Dereification

Marx's Method as Social Abstraction

Relations Constituting the Forces of Production

Scientistic versus Critical Marxism

Critical Marxism Post-1960s: Capitalist Relations Restructuring the Productive Forces

Technoscientific Innovation for Emancipatory Agendas

Technology Intensifying and/or Superseding Capitalism?

Creating Biovalue from Nature and/or Labour?

Marx, Marxism and Eurocentrism

The Cultural Logic of Postcoloniality

Postcolonial Fetishes: Culture, the West and the Rest

The Text and the Context: A Materialist Critique

Capitalism and Universalism as Postcolonial Spectres

Provincializing Chibber, Stretching Marxism

Introduction: The Fragile Alliance of Marxism and Psychoanalysis

The Unconscious Worker: Freud's Labour Theory of the Unconscious

The Capitalist Vicissitude of the Drive: A Return to Marx

Structuralist Freudo-Marxism: A Project in Critical Epistemology

Instead of a Conclusion: Analysis as Cultural Work

Political Economy and Totality

Reification and Homonormativity

55. Sociology and Marxism in the USA

The First 100 Years of Marx and Sociology

The Critical Turn to Marx in Sociology

The University in the Primacy of the Economic

The University in the Histories of Difference

Part VII Inquiries and Debates

Marxism and Intersectionality's History

Marxist Engagements with Intersectionality

Class, Classism, and Capitalism

Causation and Intersectionality

Solidarity, Separatism, and Sectarianism

Conclusion: Intersectionality and/or Marxism?

The Meaning of Self-determination

59. Digitality and Racial Capitalism

Introduction: Racial Capitalism as World Computer

Computational Racial Capitalism

Information as Real Abstraction

Information and Social Difference

Commodification and Digital Culture

‘Human Capital’ and the Derivative Condition

Race, Informatics, and the Violence of Abstraction

60. Race, Imperialism and International Development

Introduction: Re-engaging with Marxism as a Methodology of the Global South

Race and Racism in International Development

Decolonial Approaches to Race and Development

Embracing the State in the Global South

Critiques of Good Governance Discourses

Forms of Struggle Beyond Capital–Labour Relations

Critical Advertising Scholarship and ‘Race'

Advertising Spectacles and the Naturalisation of Capitalist Relations

Selling Neo-Liberal Multiculturalism

The Fetishisation and Mystification of Factory Labour

62. Dependency Theory and Indigenous Politics

A Brief History of Dependency Theory

Useful Analytical Features of Dependency Theory for the Present

Dependency Theory in Indian Country

Revisiting Dependency Theory in Indian Country

Between Evolutionism and Primitive Communism: The Late Marx

Relations of Reproduction: Claude Meillassoux's Economic Anthropology

Conclusion: Dialectics of the Primitive

Production, Reproduction, and Social Reproduction

Mainstream and Marxist Criticisms

Circulation Struggles and Surplus Population

66. Postsecularism and the Critique of Religion

Of Triangles, Turns, and Returns

Conclusion: The Matter of Science

From Utopian Socialism to Marx and Engels

Marxism as Concrete Utopia: Ernst Bloch

Perspectives for an Alternative

Critiques of the Affective Turn

Feminist Criticisms of the Affective Turn

Affect, Resistance and Organising

Conclusion: A Marxist Theory of Affect?

‘…So That the Humble Worker or Peasant Could Understand Marx's Capital'

A Figurative Understanding of Capital

The Opaque Image of Capitalism

Excursus: The Problem of the Localization of Value

The Horrors of Capital and Capital

The Horrors of Primitive Accumulation and Racial Capitalism

The Horrors of Real Estate and Speculation

The Horrors of Feminization and Automation

74. Three Debates in Marxist Feminism

The Debate over Domestic Labor

75. Triple Exploitation, Social Reproduction, and the Agrarian Question in Japan

Uno Kōzō on Japan's Agrarian Question (Nōgyō Mondai)

Suiheisha Women's Articulation of Triple Exploitation

The Formation of the Alliance of the Unemployed in Mie Prefecture

Early-Twentieth-Century Thought: Alexandra Kollontai and Emma Goldman

Prostitution and Pornography: The Women's Movement, 1970s–1980s

The Social Factory and Sexual Work

Prostitution as Sexual Labour and Survival

Prostitution and Pornography: Sexual Domination, Sexual Pleasure

Sex Work Is Work: Contemporary Debates

Un/Freedom, ‘Trafficking', and the Law

Workers, Organisers, and Political Actors

78. Domestic Labour and the Production of Labour-Power

Marx and Engels on Domestic Labour

Mechanisation, Commercialisation, State Contributions and Socialisation

The Persistence of the Gender Division of Labour

The Rise of Business Logistics

Historical Conditions for the Rise of Logistics

Logistics as the Temporalization and Spatialization of the Supply Chain

Spatial Expansion and the Supply Chain

80. Labour Struggles in Logistics

Understanding Logistics Workers’ Power

Logistics Companies and Logistics Workers

Beyond MNCs: Organising Strategies for Last-Mile Delivery and Warehousing

Introduction: Welfare from a Marxist Perspective

Different Marxist Approaches Towards Welfare

Against the ‘Illusion of State Socialism': Form-Analytic Perspectives on Welfare

From Fordist to Post-Fordist Welfare State

A New Era of Segmentation and Exclusion

‘Gendering the Welfare State', the Crisis of Social Reproduction and Community Capitalism

Conclusion: A Conservative Care Regime in Trouble

Analysing Single Aspects of the City, Within General Marxian Frameworks

Bringing the City into the General Apparatus of Marxism

Taking Concepts from Marx into New Places

Cities as Places for Resistance, Activism and Class Conflicts

Knowledge, Language, and Production

Language, Communication, and Finance

Immaterial Labour and Mass Intellectuality

Cognitive Labour and Feminisation

Critiques of the Cognitive Capitalism Hypothesis

The Main Characteristics of Bio-Cognitive Capitalism

Which Kind of Subsumption in Bio-Cognitive Capitalism?

Philosophical Justifications of Intellectual Property

Historical Developments of Intellectual Property

Intellectual Property as a Site of Struggle

Borders, Boundaries, and Globalization

Bordering Devices in Marx's Analysis of So-Called Primitive Accumulation

The World Market and the ‘International’ Division of Labor

Producing and Reproducing Labor Power

Table of Contents

List of Figures

Notes on the Editors and Contributors

Editors’ Introduction

Volume 1

Part I Reworking the critique of political economy

1 Merchant Capitalism

2 Mode of Production

3 Social Reproduction Feminisms

4 Rent

5 Value

6 Money and Finance

7 Labour

8 Automation

9 Methods

10 The Transformation Problem

Part II Forms of domination, subjects of struggle

11 Class

12 Punishment

13 Race

14 Slavery and Capitalism

15 Gender

16 Servants

Part III Political perspectives

17 Politics

18 Revolution

19 State

20 Nationalism and the National Question

21 Crisis

22 Communism

23 Imperialism

Part IV Philosophical dimensions

24 Totality

25 Dialectics

26 Time

27 Space

28 Alienation

29 Praxis

30 Fetishism

31 Ideology-Critique and Ideology-Theory

32 Real Abstraction

33 Subsumption

Volume 2

Part V Land and existence

34 Primitive Accumulation, Globalization and Social Reproduction

35 Commons

36 Extractivism

37 Agriculture

38 Energy and Value

39 Climate Change

Part VI Domains

40 Anthropology

41 Art

42 Architecture

43 Culture

44 Literary Criticism

45 Poetics

46 Communication

47 International Relations

48 Law

49 Management

50 The End of Philosophy

51 Technoscience

52 Postcolonial Studies

53 Psychoanalysis

54 Queer Studies

55 Sociology and Marxism in the USA

56 The University

Volume 3

Part VII Inquiries and debates

57 Intersectionality

58 Black Marxism

59 Digitality and Racial Capitalism

60 Race, Imperialism and International Development

61 Advertising and Race

62 Dependency Theory and Indigenous Politics

63 The Primitive

64 Social Movements

65 Riot

66 Postsecularism and the Critique of Religion

67 Utopia

68 Affect

69 The Body

70 Animals

71 Desire

72 Filming Capital

73 Horror Film

74 Three Debates in Marxist Feminism

75 Triple Exploitation, Social Reproduction, and the Agrarian Question in Japan

76 Prostitution and Sex Work

77 Work

78 Domestic Labour and the Production of Labour-Power

79 Logistics

80 Labour Struggles in Logistics

81 Welfare

82 The Urban

83 Cognitive Capitalism

84 Bio-Cognitive capitalism

85 Intellectual Property

86 Deportation

87 Borders

Index

The SAGE Handbook of Marxism

The SAGE Handbook of Marxism

The SAGE Handbook of Marxism intends to set the agenda for Marxist understandings of the present and for the future. It will provide an in-depth cartography of – and original contribution to – contemporary Marxist theory and research, showcasing the vitality and range of today's Marxisms.

The Handbook sets out from the premise that it is possible to bring together diverse work across the disciplines to demonstrate what is living and lively in Marxist thought, providing a transdisciplinary ‘state of the art’ of Marxism, while inspiring contributions to areas of research that still remain, in some cases, embryonic. The aim is to demonstrate how attention to shifting social and cultural realities has compelled contemporary researchers to revisit and renovate classic Marxian concepts as well as to elaborate – in dialogue with other intellectual traditions – new frameworks for the analysis and critique of contemporary capitalism.

The past decade has witnessed a resurgent interest in Marxism within and without the academy. This renaissance of sorts cannot be framed, however, as a simple return of Marxism. The multiple crises of Marxism since the 1980s – in both political and academic life – have had lasting and in some cases irreversible effects for certain understandings of Marxist theory. Yet it is also true that theoretical approaches that largely defined themselves by contrast with Marxism – from postcolonial theory to deconstruction, from post-Marxism to certain varieties of feminism – have encountered serious limits when it comes to thinking the patterns of change and domination that define capitalism.

The SAGE Handbook of Marxism intends to advance the debate with essays that rigorously map and renew the concepts that have provided the groundwork and main currents for Marxist theory, and to showcase interventions that set the agenda for Marxist research in the twenty-first century.

The SAGE Handbook of Marxism

Edited by

Beverley Skeggs

Sara R. Farris

Alberto Toscano

Svenja Bromberg

Los Angeles

London

New Delhi

Singapore

Washington DC

Melbourne

SAGE Publications Ltd

1 Oliver's Yard

55 City Road

London EC1Y 1SP

SAGE Publications Inc.

2455 Teller Road

Thousand Oaks, California 91320

SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd

B 1/I 1 Mohan Cooperative Industrial Area

Mathura Road

New Delhi 110 044

SAGE Publications Asia-Pacific Pte Ltd

3 Church Street

#10-04 Samsung Hub

Singapore 049483

Editor: Robert Rojek

Editorial Assistant: Umeeka Raichura

Production Editor: Manmeet Kaur Tura

Copyeditor: Sunrise Setting

Proofreader: Sunrise Setting

Indexer: KnowledgeWorks Global Ltd.

Marketing Manager: Susheel Gokarakonda

Cover Design: Naomi Robinson

Typeset by KnowledgeWorks Global Ltd.

Printed in the UK

At SAGE we take sustainability seriously. Most of our products are printed in the UK using responsibly sourced papers and boards. When we print overseas we ensure sustainable papers are used as measured by the PREPS grading system. We undertake an annual audit to monitor our sustainability.

Introduction & editorial arrangement © Beverley Skeggs, Sara R. Farris, Alberto Toscano, & Svenja Bromberg, 2022

Chapter 1 © Jairus Banaji, 2022

Chapter 2 © John Haldon, 2022

Chapter 3 © Tithi Bhattacharya, Sara R. Farris & Sue Ferguson, 2022

Chapter 4 © Stefano Dughera & Carlo Vercellone, 2022

Chapter 5 © Tommaso Redolfi Riva, 2022

Chapter 6 © Jim Kincaid, 2022

Chapter 7 © Guido Starosta, 2022

Chapter 8 © Jason E. Smith, 2022

Chapter 9 © Patrick Murray, 2022

Chapter 10 © Riccardo Bellofiore & Andrea Coveri, 2022

Chapter 11 © Beverley Skeggs, 2022

Chapter 12 © Alessandro De Giorgi, 2022

Chapter 13 © Brenna Bhandar, 2022

Chapter 14 © Leonardo Marques, 2022

Chapter 15 © Sara R. Farris, 2022

Chapter 16 © Laura Schwartz, 2022

Chapter 17 © Panagiotis Sotiris, 2022

Chapter 18 © Neil Davidson, 2022

Chapter 19 © Heide Gerstenberger, 2022

Chapter 20 © Gavin Walker, 2022

Chapter 21 © Ken C. Kawashima, 2022

Chapter 22 © Alberto Toscano, 2022

Chapter 23 © Salar Mohandesi, 2022

Chapter 24 © Chris O'Kane, 2022

Chapter 25 © Harrison Fluss, 2022

Chapter 26 © Massimiliano Tomba, 2022

Chapter 27 © Kanishka Goonewardena, 2022

Chapter 28 © Amy E. Wendling, 2022

Chapter 29 © Miguel Candioti, 2022

Chapter 30 © Anselm Jappe, 2022

Chapter 31 © Jan Rehmann, 2022

Chapter 32 © Elena Louisa Lange, 2022

Chapter 33 © Andrés Saenz de Sicilia, 2022

Chapter 34 © Silvia Federici, 2022

Chapter 35 © Massimo De Angelis, 2022

Chapter 36 © Verónica Gago, 2022

Chapter 37 © Kohei Saitoa, 2022

Chapter 38 © George Caffentzis, 2022

Chapter 39 © Matt Huber, 2022

Chapter 40 © Erica Lagalisse, 2022

Chapter 41 © Gail Day, Steve Edwards & Marina Vishmidt, 2022

Chapter 42 © Luisa Lorenza Corna, 2022

Chapter 43 © Jeremy Gilbert, 2022

Chapter 44 © Brent Ryan Bellamy, 2022

Chapter 45 © Daniel Hartley, 2022

Chapter 46 © Nicholas Thoburn, 2022

Chapter 47 © Maïa Pal, 2022

Chapter 48 © Robert Knox, 2022

Chapter 49 © Gerard Hanlon, 2022

Chapter 50 © Roberto Mozzachiodi, 2022

Chapter 51 © Les Levidow and Luigi Pellizzoni, 2022

Chapter 52 © Jamila M. H. Mascat, 2022

Chapter 53 © Samo Tomšič, 2022

Chapter 54 © Peter Drucker, 2022

Chapter 55 © David Fasenfest and Graham Cassano, 2022

Chapter 56 © Roderick A. Ferguson, 2022

Chapter 57 © Ashley J. Bohrer, 2022

Chapter 58 © Asad Haider, 2022

Chapter 59 © Jonathan Beller, 2022

Chapter 60 © Kalpana Wilson, 2022

Chapter 61 © Anandi Ramamurthy, 2022

Chapter 62 © Andrew Curley, 2022

Chapter 63 © Miri Davidson, 2022

Chapter 64 © Jeffery R. Webber, 2022

Chapter 65 © Joshua Clover, 2022

Chapter 66 © Gregor McLennan, 2022

Chapter 67 © Chiara Giorgi, 2022

Chapter 68 © Emma Dowling, 2022

Chapter 69 © Søren Mau, 2022

Chapter 70 © Oxana Timofeeva, 2022

Chapter 71 © Hannah Proctor, 2022

Chapter 72 © Pietro Bianchi, 2022

Chapter 73 © Johanna Isaacson & Annie McClanahan, 2022

Chapter 74 © Cinzia Arruzza, 2022

Chapter 75 © Wendy Matsumura, 2022

Chapter 76 © Katie Cruz and Kate Hardy, 2022

Chapter 77 © Jamie Woodcock, 2022

Chapter 78 © Rohini Hensman, 2022

Chapter 79 © Charmaine Chua, 2022

Chapter 80 © Jeremy Anderson, 2022

Chapter 81 © Tine Haubner, 2022

Chapter 82 © Ståle Holgersen, 2022

Chapter 83 © David Harvie & Ben Trott, 2022

Chapter 84 © Andrea Fumagalli, 2022

Chapter 85 © Paul Rekret & Krystian Szadkowski, 2022

Chapter 86 © Nicholas De Genova, 2022

Chapter 87 © Sandro Mezzadra & Brett Neilson, 2022

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form, or by any means, only with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021949078

British Library Cataloguing in Publication data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

978-1-4739-7423-4

Contents

List of Figures

Notes on the Editors and Contributors

Editors’ Introduction

Volume 1

Part I Reworking the critique of political economy

1 Merchant Capitalism

2 Mode of Production

3 Social Reproduction Feminisms

4 Rent

5 Value

6 Money and Finance

7 Labour

8 Automation

9 Methods

10 The Transformation Problem

Part II Forms of domination, subjects of struggle

11 Class

12 Punishment

13 Race

14 Slavery and Capitalism

15 Gender

16 Servants

Part III Political perspectives

17 Politics

18 Revolution

19 State

20 Nationalism and the National Question

21 Crisis

22 Communism

23 Imperialism

Part IV Philosophical dimensions

24 Totality

25 Dialectics

26 Time

27 Space

28 Alienation

29 Praxis

30 Fetishism

31 Ideology-Critique and Ideology-Theory

32 Real Abstraction

33 Subsumption

Volume 2

Part V Land and existence

34 Primitive Accumulation, Globalization and Social Reproduction

35 Commons

36 Extractivism

37 Agriculture

38 Energy and Value

39 Climate Change

Part VI Domains

40 Anthropology

41 Art

42 Architecture

43 Culture

44 Literary Criticism

45 Poetics

46 Communication

47 International Relations

48 Law

49 Management

50 The End of Philosophy

51 Technoscience

52 Postcolonial Studies

53 Psychoanalysis

54 Queer Studies

55 Sociology and Marxism in the USA

56 The University

Volume 3

Part VII Inquiries and debates

57 Intersectionality

58 Black Marxism

59 Digitality and Racial Capitalism

60 Race, Imperialism and International Development

61 Advertising and Race

62 Dependency Theory and Indigenous Politics

63 The Primitive

64 Social Movements

65 Riot

66 Postsecularism and the Critique of Religion

67 Utopia

68 Affect

69 The Body

70 Animals

71 Desire

72 Filming Capital

73 Horror Film

74 Three Debates in Marxist Feminism

75 Triple Exploitation, Social Reproduction, and the Agrarian Question in Japan

76 Prostitution and Sex Work

77 Work

78 Domestic Labour and the Production of Labour-Power

79 Logistics

80 Labour Struggles in Logistics

81 Welfare

82 The Urban

83 Cognitive Capitalism

84 Bio-Cognitive capitalism

85 Intellectual Property

86 Deportation

87 Borders

Index

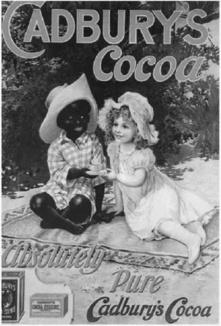

61.1 Cadbury's cocoa advertisement c 1900, courtesy of Cadbury's and MDLZ1135

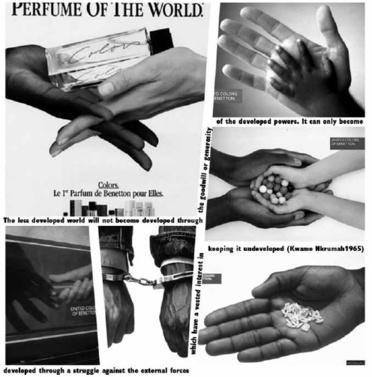

61.2 Hands (Anandi Ramamurthy 2020)1139

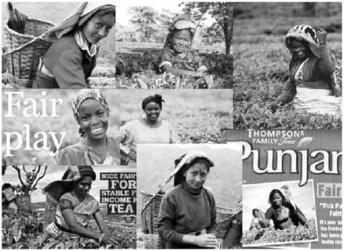

61.3 The smiling worker1143

Notes on the Editors and Contributors

The Editors

Sara R. Farris

is a Reader in the Department of Sociology at Goldsmiths University of London. She has published widely on issues of gender, migration, social reproduction and racism/nationalism as well as social and political theory. She is the author of Max Weber's theory of personality. Individuation, politics and orientalism in the sociology of religion (Brill Academic Publishers 2013) and In the name of women's rights. The rise of Femonationalism (Duke University Press 2017).

Beverley Skeggs

is Professor of Sociology at Lancaster University. She has published The Media; Issues in Sociology; Feminist Cultural Theory; Formations of Class and Gender; Class, Self, Culture Sexuality and the Politics of Violence and Safety (with Les Moran) and Feminism after Bourdieu (with Lisa Adkins), and with Helen Wood, Reacting to Reality TV: Audience, Performance, Value and Reality TV and Class. As an ESRC Professorial Fellow she developed a “sociology of values and value'’ and whilst Director of the Atlantic Fellows Programme, established the ‘Global Economies of Care’ theme at the LSE. She is also the Chief Executive of The Sociological Review Foundation.

Alberto Toscano

is Professor of Critical Theory in the Department of Sociology and Co-Director of the Centre for Philosophy and Critical Theory at Goldsmiths, University of London, and Visiting Professor at the School of Communications at Simon Fraser University. Since 2004 he has been a member of the editorial board for the journal Historical Materialism: Research in Critical Marxist Theory and is series editor of The Italian List for Seagull Books. He is the author of The Theatre of Production (2006), Fanaticism: On the Uses of an Idea (2010; 2017, 2nd edn) and Cartographies of the Absolute (2015, with Jeff Kinkle). A translator of Antonio Negri, Alain Badiou, Franco Fortini, Furio Jesi and others, Toscano has published widely on critical theory, philosophy, politics and aesthetics.

Svenja Bromberg

is a Lecturer in the Department of Sociology at Goldsmiths, University of London. Her research and teaching are in continental philosophy and social theory with a focus on issues of emancipation, radical democracy, and materialist philosophies. She completed her PhD “Thinking ‘Emancipation’ after Marx - A Conceptual Analysis of Emancipation between Citizenship and Revolution in Marx and Balibar” in 2016. Svenja is a co-editor of Eurotrash (published 2016 at Merve Verlag, Berlin together with Birthe Mühlhoff and Danilo Scholz) and a member on the editorial board of the journal Historical Materialism. She recently published ‘Marx, an ‘Antiphilosopher'? Or Badiou's Philosophical Politics of Demarcation’ in: Völker, J. (ed) (2019), Badiou and the German Tradition of Philosophy, London: Bloomsbury Academic.

The Contributors

Jeremy Anderson

is Head of Strategic Research at the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF) and previously worked for the Service and Food Workers’ Union of Aotearoa New Zealand. His PhD (Geography, Queen Mary, University of London) analyses transnational union organising campaigns.

Cinzia Arruzza

is Associate Professor of Philosophy at the New School for Social Research. She works on ancient Greek philosophy and Marxist and feminist theory. She is the author of Dangerous Liaisons: The Marriages and Divorces of Marxism and Feminism (2013), Plotinus. Ennead II 5. On What Is Potentially and What Actually (2015), A Wolf in the City: Tyranny and the Tyrant in Plato's Republic (2018) and co-author of Feminism for the 99%. A Manifesto (2019).

Jairus Banaji

studied Classics, Ancient History and Modern Philosophy at Oxford in the late 1960s and eventually returned to India to do Modern History at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi soon after that institution was founded. After working with the unions in Bombay for about 10 years, he returned to Oxford to do a DPhil in Roman history. This was later published as Agrarian Change in Late Antiquity: Gold, Labour, and Aristocratic Dominance (2007, 2nd edn). He has been a Research Associate with the Department of Development Studies, SOAS, University of London for a number of years, and is associated with the journals Journal of Agrarian Change and Historical Materialism. His latest books include Exploring the Economy of Late Antiquity: Selected Essays (2016) and A Brief History of Commercial Capitalism (2020).

Brent Ryan Bellamy

is an instructor in the English and Cultural Studies departments at Trent University. He is the author of Remainders of the American Century: Post-Apocalyptic Novels in the Age of US Decline (2021) and co-editor of An Ecotopian Lexicon (2019) and Materialism and the Critique of Energy (2018). He teaches courses in science fiction, graphic fiction, American literature and culture, and critical world building. He currently studies narrative, US literature and culture, science fiction, and the cultures of energy.

Jonathan Beller

is Professor of Humanities and Media Studies and co-founder of the Graduate Program in Media Studies at Pratt Institute. His books include The Cinematic Mode of Production: Attention Economy and the Society of the Spectacle (2006), Acquiring Eyes: Philippine Visuality, Nationalist Struggle, and the World-Media System (2006), The Message is Murder: Substrates of Computational Capital (2017) and The World Computer: Derivative Conditions of Racial Capitalism (2021). He is a member of the Social Text editorial collective.

Riccardo Bellofiore

was Professor of Political Economy at the University of Bergamo, now retired. There he taught macroeconomics, monetary economics, international monetary economics and history of economic thought. His research interests include Marxian theories of value and crisis, the dynamics of the capitalist contemporary economy, macro-monetary and financial approaches and the philosophy of economics.

Brenna Bhandar

is Reader in Law and Critical Theory at SOAS, University of London. She is the author of Colonial Lives of Property: Law, Land and Racial Regimes of Ownership (2018) and co-editor with Rafeef Ziadah of Revolutionary Feminisms: Conversations on Collective Action and Radical Thought (2020) and with Jon Goldberg-Hiller of Plastic Materialities: Politics, Legality and Metamorphosis in the Work of Catherine Malabou (2015). She is a member of the Radical Philosophy editorial collective.

Tithi Bhattacharya

is a Professor of South Asian History at Purdue University. She is the author of The Sentinels of Culture: Class, Education, and the Colonial Intellectual in Bengal (Oxford University Press, 2005) and the editor of the now classic study, Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping Class, Recentering Oppression (Pluto Press, 2017). Her recent coauthored book includes the popular Feminism for the 99%: A Manifesto (Verso, 2019) which has been translated in over 25 languages. She writes extensively on Marxist theory, gender, and the politics of Islamophobia. Her work has been published in the Journal of Asian Studies, South Asia Research, Electronic Intifada, Jacobin, Salon.com, The Nation, and the New Left Review. She is on the editorial board of Studies on Asia and Spectre.

Pietro Bianchi

is Assistant Professor of Critical Theory at the English Department of the University of Florida. He has written Jacques Lacan and Cinema. Imaginary, Gaze, Formalisation (2017) and several articles and essays on Lacanian psychoanalysis, film studies and Marxism in journals such as Crisis&Critique, Angelaki, Filozofski Vestnik, Fata Morgana and S: Journal of the Circle for Lacanian Ideology Critique. He also regularly collaborates as a film critic with Italian media outlets Cineforum, Doppiozero, FilmTv and DinamoPress.

Ashley J. Bohrer

is a scholar-activist based in Chicago. She holds a PhD in Philosophy and is currently Assistant Professor of Gender and Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame. Her academic work focuses on the relationship between exploitation and oppression under capitalism. She is the author of Marxism and Intersectionality: Race, Gender, Class and Sexuality under Contemporary Capitalism (2019).

George Caffentzis

is a philosophy scholar and activist. He received his PhD in Philosophy from Princeton University in 1977, with a dissertation entitled ‘Does Quantum Mechanics Necessitate a Theoretical Revolution in Logic?'. He has taught logic and philosophy of science in universities in the USA and at the University of Calabar, in Nigeria, and he has lectured in several universities in Europe and Latin America. His scholarly focus since the 1980s has been the philosophy of money and Marxist theory. Caffentzis is now a retired Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at the University of Southern Maine. His published work includes a three-volume study of the ‘British empiricist’ philosophers’ contribution to the development of monetary theory and empire: Clipped Coins, Abused Words and Civil Government: John Locke's Philosophy of Money (1989), Exciting the Industry of Mankind: George Berkeley's Philosophy of Money (2000) and Civilizing Money: David Hume's Philosophy of Money, which is now under contract with Pluto Press. Other works include In Letters of Blood and Fire (2013), recently published in Spanish, No Blood for Oil (2017) and A Thousand Flowers: Social Struggle against Structure Adjustment in African Universities (2000, co-edited with Silvia Federici and Ousseina Alidou).

Miguel Candioti

has a degree in Philosophy (National University of Rosario), a Master's degree in Interculturality (University of Bologna) and a doctorate in Humanities (Pompeu Fabra University). He has studied deeply the development of the concept of praxis in Marx and early Italian theoretical Marxism (from Antonio Labriola to Antonio Gramsci). Among his published articles are ‘The Enigma of the Theses on Feuerbach and the secret thereof’ (2014), ‘Fetishism of use value? Towards a Marxist theory of value and power in general’ (2015), ‘Karl Marx and the practical materialist theory of alienation of the (Collective) Human Subject’ (2016) and ‘The Revolutionary Moral Idealism Inherent in the Practical Materialism of Karl Marx’ (2017). Since 2015 he has been working as a professor and Researcher at the National University of Jujuy, where he leads the chairs of Political Philosophy and Metaphysics.

Graham Cassano

is an Associate Professor of Sociology at Oakland University. His most recent books include A New Kind of Public: Community, Solidarity, and Political Economy in New Deal Cinema, 1935–48, Eleanor Smith's Hull House Songs: The Music of Protest and Hope in Jane Addams's Chicago and the forthcoming Urban Emergency: (Mis)Management and the Crisis of Neoliberalism.

Charmaine Chua

is Assistant Professor of Global Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Her work explores the co-constitution of logistical technologies, global supply chains and racialised dispossession in the context of US empire. Charmaine holds a PhD in Political Science from the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities. She is the reviews and magazine editor for Environment and Planning D: Society and Space and a member of the Abolition Journal and Amazonians United collectives. Her work has been published in Theory and Event, Historical Materialism and Environment and Planning D, among other venues.

Joshua Clover

is the author of seven books, including Roadrunner (2021) as well as Riot.Strike.Riot: the New Era of Uprisings, a political economy of social movements, with recent editions in French, German, Turkish and Swedish. He is currently Professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of California Davis as well as Affiliated Professor of Literature and Modern Culture at the University of Copenhagen.

Luisa Lorenza Corna

teaches at Middlesex University and at the University of Portsmouth. She is also a Visiting Lecturer at the University of Milan/Bicocca's Master's in Critical Theory. Her main concern is the relationship between politics, art and architectural theory. Since completing her PhD her research has developed along three main lines: Marxism and theories of the city, with a focus on the postwar Italian context; art and architectural historiographies; and the influence of feminist epistemologies on histories and theories of art. She has written for various journals, including Parallax, Historical Materialism, Radical Philosophy, Art Monthly, Texte Zur Kunst and Jacobin. At the moment she is completing, with Jamila Mascat and Matthew Hyland, an anthology of Carla Lonzi's art historical and feminist writings for Seagull Books. She is also working on her first monograph, tentatively titled Fugitive Lives, which examines the theme of leaving the art/architectural world from the point of view of the critic.

Andrea Coveri

holds a PhD in Economics from Marche Polytechnic University. He is currently Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Applied Economics at the University of Urbino, where he taught global political economics and microeconomics. His research interests include Marxian theory of value, global value chains, innovation dynamics and industrial policy.

Katie Cruz

is a Senior Lecturer in Law at the University of Bristol. She researches sex work, trafficking for sexual exploitation and sex tourism through the lens of Marxist feminist legal theory. Katie is currently working on a monograph about sex-worker-rights activists’ social and legal use of rights discourse in the UK. This empirically grounded research investigates the possibilities and limits of rights for sex workers using legal doctrinal methods and Marxist feminist theory. Katie regularly collaborates with sex-worker-rights activists in the UK and has a long-standing history of sex-work and feminist activism. She is Co-Director of the Bristol Centre for Law at Work and an editor of the journal Feminist Legal Studies.

Andrew Curley

(Diné) is an Assistant Professor in the School of Geography, Development and Environment at the University of Arizona. His research focuses on the incorporation of Indigenous nations into colonial economies. His recent publications speak to the role of Diné coal workers and environmentalists in Navajo politics of energy transition. He has also published on Indigenous water law and water rights.

Miri Davidson

is a PhD student at Queen Mary, University of London. She writes about the history of anthropology and the French left.

Neil Davidson.

Born in Aberdeen, Neil Davidson (1957–2020) was an activist and a historical sociologist who wrote on revolution and nationalism. For much of his working life, Davidson was a civil servant in Scotland. In 2008 he began teaching at the University of Strathclyde and in 2013 joined the Sociology Department at Glasgow. Davidson was the author of three monographs: The Origins of Scottish Nationhood (2000), Discovering the Scottish Revolution 1692–1746 (2003), which was awarded both the Isaac and Tamara Deutscher Memorial Prize and the Saltire Society's Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun Award, and the monumental How Revolutionary Were the Bourgeois Revolutions? (2012). He published three collections of essays with Haymarket Press and co-edited Alasdair MacIntyre's Engagement with Marxism (2008), Neoliberal Scotland (2010), The Longue Durée of the Far-Right (2014) and No Problem Here: Understanding Racism in Scotland (2018). At the time of his premature death, Davidson was working on numerous projects, including a book on uneven and combined development; a response to the critics of his work on bourgeois revolutions; a study of neoliberalism; and a book on the ‘actuality’ of revolution. It is hoped that these and other works will be published in the near future.

Gail Day's

Dialectical Passions: Negation in Postwar Art Theory (2011) was shortlisted for the Isaac and Tamara Deutscher Memorial Prize. She is Professor of Art History and Critical Theory, and Director of Research in the School of Fine Art, History of Art and Cultural Studies at the University of Leeds, where she is Co-Founder of the Centre for Critical Materialist Studies. Gail is also part of the research collective Marxism in Culture (at the Institute of Historical Research, London). With Steve Edwards and colleagues from Universidade de São Paulo she initiated the project Aesthetic Form & Uneven Modernities, and she belongs to DESFORMAS (Centro de estudos Desmanche e Formação de Sistemas Simbólicos at USP).

Massimo De Angelis

is an author, teacher and activist who has engaged with the question of post-capitalist transformation for over four decades. He is Emeritus Professor at the University of East London. He is the founding editor of The Commoner, a web journal that began to problematise the role of the commons for radical transformation as early as 2001. He is the author of several publications on crises, governance, value, social revolution and the commons. His last two books, Omnia Sunt Communia (2017) and The Beginning of History (2007), develop a framework and a theory of hope that both recognise the systemic patterns and horrors of capitalist development and the ruptures and emergence of post-capitalist systems based on struggles and the commons.

Nicholas De Genova

is Professor and Chair of the Department of Comparative Cultural Studies at the University of Houston. He previously held teaching appointments in urban and political geography at King's College London, and in anthropology at Stanford, Columbia and Goldsmiths, University of London, as well as visiting professorships or research positions at the Universities of Warwick, Bern and Amsterdam. He is the author of Working the Boundaries: Race, Space, and ‘Illegality’ in Mexican Chicago (2005), co-author of Latino Crossings: Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and the Politics of Race and Citizenship (2003), editor of Racial Transformations: Latinos and Asians Remaking the United States (2006), co-editor of The Deportation Regime: Sovereignty, Space, and the Freedom of Movement (2010), editor of The Borders of ‘Europe': Autonomy of Migration, Tactics of Bordering (2017) and co-editor of Roma Migrants in the European Union: Un/Free Mobility (2019).

Alessandro De Giorgi

is Professor of Justice Studies at San Jose State University. He received his PhD in Criminology from Keele University in 2005. Before joining SJSU, he was a Research Fellow in Criminology at the University of Bologna and a Visiting Scholar at the Center for the Study of Law and Society, University of California Berkeley. His research interests include critical theories of punishment and social control, urban ethnography and radical political economy. He is the author of the book Rethinking the Political Economy of Punishment: Perspectives on Post-Fordism and Penal Politics (2006) as well as of several articles in journals such as Punishment & Society, Theoretical Criminology, Critical Criminology and Social Justice. His most recent work is ethnographic research on the socioeconomic dimensions of mass incarceration and prisoner re-entry in Oakland, California.

Emma Dowling

is a sociologist and political scientist at the University of Vienna, where she is Assistant Professor of Sociology. Previously, she held academic positions in Germany and the UK. Her research interests include social change, social movements, emotional and affective labour, gender, care and social reproduction, financialisation and feminist political economy. She has published in journals such as Sociology, New Political Economy and Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, and she is the author of the monograph The Care Crisis (2021).

Peter Drucker

has been a socialist feminist, anti-imperialist and LGBTIQ activist for over 40 years in New York, San Francisco, Amsterdam and Rotterdam. Trained as a historian (BA, Yale, 1979) and political scientist (PhD, Columbia, 1993), he writes on Marxist and queer theory. From 1993 to 2006 he was Co-Director of the Amsterdam-based International Institute for Research and Education, and he is still an IIRE Fellow and Lecturer. He is the author of Max Shachtman: A Socialist Odyssey through the ‘American Century' (1993) and Warped: Gay Normality and Queer Anti-Capitalism (2015), and the editor of the anthology Different Rainbows (2000). He has written for publications including Gay Community News, Against the Current, International Viewpoint, Grenzeloos, New Left Review, the Journal of European Studies, Development in Practice, Historical Materialism, the Journal of Middle East Women's Studies, Salvage, Rampant and Mediations. He helped initiate the Sexuality and Political Economy Network.

Stefano Dughera,

economist, is Research Fellow (Postdoc) at the University of Turin, Department of Economics and Statistics. His research lies at the intersections of labour and institutional economics. He is co-author with Carlo Vercellone of ‘Metamorphosis of the Theory of Value and Becoming-Rent of Profit', in Cognitive Capitalism, Welfare and Labour: The Commonfare Hypothesis (2019).

Steve Edwards

is Professor of History and Theory of Photography at Birkbeck, University of London. His publications include The Making of English Photography, Allegories (2006), Photography: A Very Short Introduction (2006) and Martha Rosler: The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems (2012). He is a member of the editorial boards for the Oxford Art Journal and the Historical Materialism book series as well as a convenor for the long-running University of London research seminar Marxism in Culture. He is currently working on a book on artist Allan Sekula with Gail Day and completing a major study of early English photography.

David Fasenfest

is an Associate Professor of Sociology and Urban Affairs, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, Wayne State University, and the editor of Critical Sociology and two book series, Studies in Critical Social Science and New Scholarship in Political Economy, both with Brill. His research focuses on inequality, urban development and Marxism. He is the author of ‘Monsieur Le Capital and Madame La Terre on the Brink’ (2017, with Penelope Ciancanelli, in Towards Just and Sustainable Economies: Comparing Social and Solidarity Economy in the North and South), ‘Marx, Marxism and Human Rights’ (2016, Critical Sociology), ‘Marxist Sociology and Human Rights’ (2013, in the Handbook of Sociology and Human Rights) and Marx Matters (forthcoming, Brill).

Silvia Federici

is a feminist activist, teacher and writer. She was one of the founders of the International Feminist Collective, the organisation that launched the Campaign for Wages for Housework. She is the author of books and essays on political philosophy, feminist theory, cultural studies and education. Her published works include Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation (2004), Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction and Feminist Struggle (2012) and Re-Enchanting the World: Feminism and the Politics of the Commons (2018). She is Emerita Professor at Hofstra University.

Roderick A. Ferguson

is the William Robertson Coe Professor of Women's, Gender and Sexuality Studies and American Studies at Yale University. He received his BA from Howard University and his PhD from the University of California, San Diego. An interdisciplinary scholar, his work traverses such fields as American studies, gender studies, queer studies, cultural studies, African American Studies, sociology, literature and education. He is the author of One-Dimensional Queer (2019), We Demand: The University and Student Protests (2017), The Reorder of Things: The University and Its Pedagogies of Minority Difference (2012) and Aberrations in Black: Toward a Queer of Color Critique (2004). He is co-editor with Grace Hong of the anthology Strange Affinities: The Gender and Sexual Politics of Comparative Racialization (2011). He is also co-editor with Erica Edwards and Jeffrey Ogbar of Keywords of African American Studies (2018).

Sue Ferguson

is a Marxist-Feminist scholar and activist and Associate Professor Emerita at Wilfrid Laurier University and Adjunct Professor with the Graduate School at Rutgers University. Her published work includes articles on feminist theory, childhood and capitalism, and Canadian political discourse. Her book, Women and Work: Social Reproduction, Feminism and Labour was published in 2020 by Pluto Press and has been translated to Spanish by Sylone/Viento Sur. Ferguson is also a member of Faculty4Palestine and on the editorial board of Midnight Sun.

Harrison Fluss

is a philosophy Professor at Manhattan College in New York City, and a corresponding editor at Historical Materialism. He earned his PhD in philosophy at Stony Brook University in New York, specialising in German Idealism. He is the author of the book Prometheus and Gaia: Technology, Ecology, and Anti-Humanism (2021), and his writings have appeared in Left Voice, Jacobin, Salvage and The New Republic.

Andrea Fumagalli

is an activist and Professor of Economics and History of Economic Thought in the Department of Economics and Management at University of Pavia and at Iuss-Pavia. He also teaches eco-social economics at the Free University of Bolzano. He is a member of the Effimera Network and a founder member of Bin-Italy (Basic Income Network, Italy). His publications include The Crisis of the Global Economy: Financial Markets, Social Struggles and New Political Scenarios (2010, with S. Mezzadra), ‘Life Put to Work: Towards a Theory of Life-Value’ (2011, with C. Morini, Ephemera), ‘Finance, Austerity and Commonfare’ (2015, with S. Lucarelli, Theory, Culture and Society), Economia politica del comune (2017) and Cognitive Capitalism, Welfare and Labour: The Commonfare Hypothesis (2019, with A. Giuliani, S. Lucarelli and C. Vercellone).

Verónica Gago

teaches political science at the Universidad de Buenos Aires and is Professor of Sociology at the Instituto de Altos Estudios, Universidad Nacional de San Martín. She is also Researcher at the National Council of Research (CONICET). She is the author of Neoliberalism from Below: Popular Pragmatics and Baroque Economies (2014, 2017) and International Feminist (2020), and she is co-author of A Feminist Reading of Debt (2020, 2021). She coordinates the working group Popular Economies: Theoretical and Practical Mapping at Consejo Latinamericano Ciencias Sociales (CLACSO). She was part of the militant research experience Colectivo Situaciones, and she is now a member of the feminist collective Ni Una Menos.

Heide Gerstenberger

was Professor for the Theory of State and Society at the University of Bremen. She is now retired. Her research, though covering a wide range of topics, has centred on the development of capitalist states. She was also engaged in the analysis of maritime labour. Her main publications are Die subjektlose Gewalt. Theorie der Entstehung bürgerlicher Staatsgewalt (2007, translated as Impersonal Power. History and Theory of the Bourgeois State). In 2017 she published Markt und Gewalt. Die Funktionsweise des historischen Kapitalismus, which is being translated as Market and Violence: The Historical Functioning of Capitalism.

Jeremy Gilbert

is Professor of Cultural and Political Theory at the University of East London, where he has been based for many years. His most recent publications include Twenty-First-Century Socialism (2020), a translation of Maurizio Lazzarato's Experimental Politics and the book Common Ground: Democracy and Collectivity in an Age of Individualism (2013). Hegemony Now: How Big Tech and Wall Street Won the World will be published by Verso in 2022. He is the current editor of the journal New Formations and has written and spoken widely on politics, music and cultural theory, having given keynotes at numerous international conferences on these topics and on the politics and practice of cultural studies. He writes regularly for the British press (including the Guardian, the New Statesman, open Democracy and Red Pepper) and for think tanks such as IPPR and Compass. He also hosts several popular podcasts.

Chiara Giorgi

is Assistant Professor at Sapienza University of Rome, Department of Philosophy, where she teaches contemporary history. Her main research topics are the welfare state, the healthcare system, history of fascism, Italian colonialism, Italian socialism and Marxism. Her books include A Heterodox Marxist and His Century: Lelio Basso (2020, editor), Storia dello Stato sociale in Italia (forthcoming, with I. Pavan), Rileggere Il Capitale (2018, editor), Costituzione italiana: articolo 3 (2017, with M. Dogliani), Un socialista del Novecento. Uguaglianza, libertà e diritti nel percorso di Lelio Basso (2015), L'Africa come carriera. Funzioni e funzionari del colonialismo italiano (2012), La previdenza del regime. Storia dell'INPS durante il fascismo (2004) and La sinistra alla Costituente. Per una storia del dibattito istituzionale (2001).

Kanishka Goonewardena

was trained as an architect in Sri Lanka and is now Professor, Department of Geography and Planning, University of Toronto. His work has focused mostly on space and ideology, drawing from Marxist and allied critical theories, with publications in journals such as Historical Materialism, Antipode, Society and Space, Planning Theory and the International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. He co-edited Space, Difference, Everyday Life: Reading Henri Lefebvre (2008) and is currently researching the historical geography of the concept of imperialism.

Asad Haider

is the author of Mistaken Identity: Race and Class in the Age of Trump (2018) and an editor of Viewpoint Magazine.

John Haldon

is Shelby Cullom Davis '30 Professor of European History Emeritus at Princeton University. He is currently also Director of the Princeton Climate Change and History Research Initiative and Director of the Program in Medieval Studies Environmental History Lab. His research focuses on the history of the medieval eastern Roman (Byzantine) empire, in particular the period from the seventh to the twelfth centuries; on state systems and structures across the European and Islamic worlds from late ancient to early modern times; on the impact of environmental stress on societal resilience in pre-modern social systems; and on the production, distribution and consumption of resources in the late ancient and medieval world.

Gerard Hanlon

is a Professor of Organizational Sociology at the Centre for Labour and Global Production, Queen Mary University of London. Historically, his interests focused on professional labour and expertise, but more recently his work has concentrated on management theory and neoliberalism, the changing nature of work and subjectivity, the shift from a real to a total subsumption of labour to capital, innovation and entrepreneurship. Much of this more recent work is captured in his most recent book, The Dark Side of Management – A Secret History of Management Theory (2016). He is currently researching the historical relationship between the emergence of the modern military and the rise of capitalist management of the division of labour and organisation in the era of early industrial capitalism.

Kate Hardy

is an Associate Professor in Work and Employment Relations at the University of Leeds, Associate Editor of New Technology, Work and Employment and a feminist activist. Her research interests include paid and unpaid work, gender, agency, Marxist feminism, collective organising, political economy, the body, disability, sex work and social struggles. Her work has been widely published academically and in news media. Kate is committed to developing methodologies which work alongside research participants in order to undertake socially and politically transformative research. To do so, she has worked closely with AMMAR, the sex workers’ union of Argentina, other sex workers’ movements and with Focus E15, a homeless movement in East London led by single mothers. Kate is a founding member of Partisan Collective and Greater Manchester Housing Action, both based in Manchester.

Daniel Hartley

is Assistant Professor in World Literatures in English at Durham University. He is the author of The Politics of Style: Towards a Marxist Poetics (2017) and has published widely on Marxist theory and contemporary literature.

David Harvie

is the author (with The Free Association) of Moments of Excess: Movements, Protest and Everyday Life (2011) and the co-editor of Commoning (2019, with George Caffentzis and Silvia Federici). He was an editor of Turbulence: Ideas for Movement. He has also published on the political economy of education, value theory and struggles, and social finance. He is a member of the Leicester-based Centre for Philosophy and Political Economy and also of Plan C. He sings with Commoners Choir and is part of the Aftermathematics project (Twitter: @ftermathematics).

Tine Haubner

is a Research Assistant at the Chair of Political Sociology at the Sociological Institute of the Friedrich Schiller University in Jena. She researches and teaches on issues such as social reproduction, informal and voluntary work, social inequality and the welfare state. In her work she combines theoretical with qualitative-empirical research. She received her doctorate in 2016 with a thesis on exploitation in the field of informal elder care. In her dissertation, she subjects the German elder-care system to a fundamental critique and develops a feminist-theoretical concept of exploitation for sociology, which is able to think of exploitation beyond industrial profit maximisation. In doing so, she combines social exclusion, social vulnerability and the appropriation of labour in a way that considers both economic and cultural-symbolic factors of exploitation. Her current research interests focus on strategies of social reproduction beyond state, market and family. In this context, she researches voluntary work in the structural change of the welfare state and informal economies in rural poverty areas in Germany.

Rohini Hensman

is a writer and independent scholar who comes from Sri Lanka and is resident in India. She has written extensively on workers’ rights, feminism, minority rights, globalisation and a Marxist approach to struggles for democracy. Her book Workers, Unions, and Global Capitalism: Lessons from India (2011) was based on her PhD thesis for the University of Amsterdam, and her most recent book is Indefensible: Democracy, Counter-Revolution, and the Rhetoric of Anti-Imperialism (2018). She has also written two novels: To Do Something Beautiful, inspired by her work with working-class women and trade unions in Bombay, and Playing Lions and Tigers, which tells the interlocking stories of 14 women, men and children from different parts of Sri Lanka and different ethno-religious and social backgrounds as they confront political authoritarianism and war.

Ståle Holgersen

is Researcher at the Institute for Housing and Urban Research, and Department of Social and Economic Geography, Uppsala University. His research interests include urban policy, housing and class, climate change and economic and ecological crises. He is the author of Staden och Kapitalet (2017) and has published numerous articles in journals such as Antipode, Planning Theory, the International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Human Geography and Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie. He is currently Principal Investigator for two major research projects: one on the far right and climate denialism (White Skin, Black Fuel) and one on Swedish housing (The Housing Question in Times of Crisis).

Matt Huber

is an Associate Professor of Geography at Syracuse University. He is the author of Lifeblood: Oil, Freedom and the Forces of Capital (2013). He is currently working on a book on class and climate politics for Verso Books.

Johanna Isaacson

is an Instructor of English at Modesto Junior College and a founding editor of Blind Field journal. She is the author of The Ballerina and the Bull: Anarchist Utopias in the Age of Finance (2016) and the forthcoming book Stepford Daughters: Tools for Feminists in Contemporary Horror.

Anselm Jappe

is the author of Guy Debord (1993, 2016), Les Aventures de la marchandise. Pour une critique de la valeur (2003, 2017), L'Avant-garde inacceptable. Réflexions sur Guy Debord (2004), Crédit à mort (2011, translated as The Writing on the Wall, 2016), La Société autophage (2017) and Béton – Arme de construction massive du capitalisme (2020). He has contributed to the German reviews Krisis and Exit !, founded by Robert Kurz, which developed the ‘critique of value'. He currently teaches at the Fine Art Schools of Sassari, Italy, and has been visiting professor in various European and Latin American universities. He also lectured at the Ecole des hautes etudes en sciences socials and at the Collège international de philosophie, Paris.

Ken C. Kawashima

is Associate Professor at the University of Toronto, Department of East Asian Studies, and the author of The Proletarian Gamble: Korean Workers in Interwar Japan (2009), ‘Capital's Dice-Box Shaking’ (2005, Rethinking Marxism) and ‘The Hidden Area between Marx and Foucault’ (2019, positions: asia culture critique); co-editor with Robert Stolz and Fabian Schaeffer of Tosaka Jun: A Critical Reader (2014); and the English translator of Uno Kōzō's Theory of Crisis (forthcoming). He researches and teaches Marxist political economic theory; the histories of capitalism in Japan and colonial Korea; the critique of ideology, everyday life and racism; and theories of the subject. He also composes, sings and records blues music as Sugar Brown.

Jim Kincaid

taught sociology and social policy at the Universities of Aberdeen, Leeds and Bradford before early retirement to spend more time with Marx. He was a member of the editorial board of Historical Materialism, from 2002 to 2006, and has been Corresponding Editor since then. He has published in Historical Materialism and elsewhere on topics which include East Asia, the Hegel–Marx connection, the logic of Marx's Capital, financialisation and the 2008 crisis. He edited, and contributed to, symposia in Historical Materialism on the work of Chris Arthur and of Costas Lapavitsas. A selection of his publications is available on his Researchgate website.

Robert Knox

is a Senior Lecturer in Law at the School of Law and Social Justice, University of Liverpool. He is a member of the editorial boards of Historical Materialism and The London Review of International Law.

Erica Lagalisse

is an anthropologist and writer, a Postdoctoral Fellow at the London School of Economics (LSE), editor and editorial board member at The Sociological Review and Visiting Researcher at the Anarchism Research Group at the University of Loughborough. She is the author of Occult Features of Anarchism – with Attention to the Conspiracy of Kings and the Conspiracy of the Peoples (2019). Her contribution in this volume, ‘Anthropology', is inspired in part by her PhD dissertation, titled ‘“Good Politics”: Property, Intersectionality, and the Making of the Radical Self'. This ethnography explores anarchist networks crossing Québec, the USA and Mexico to examine settler ‘anarchoindigenism', and draws on anthropological, feminist and critical race theory to show how Anglo-American leftists have pre-empted the black feminist challenge of ‘intersectionality’ by recuperating its praxis within the logic of neoliberal property relations.

Elena Louisa Lange

is a philosopher and Japanologist. She is currently Senior Research Fellow and Lecturer at the University of Zurich. Her publications have appeared in Historical Materialism, Science & Society, Crisis and Critique, Consecutium Rerum, The Bloomsbury Companion to Marx, the Sage Handbook of Frankfurt School Critical Theory and others. She is co-editor of two books on Asian philosophy. Her second monograph is Value without Fetish: Uno Kôzô's Theory of Pure Capitalism in Light of Marx's Critique of Political Economy (2021). She is co-editor of the forthcoming collection The Conformist Rebellion: Marxist Responses to the Contemporary Left.

Les Levidow

is a Senior Research Fellow at the Open University, where he has studied agri-environmental-technology issues, especially techno-market fixes, consequent controversy and alternative agendas. A long-running case study was the agri-biotech controversy, focusing on the EU, USA and their trade conflicts. This research resulted in two books: Governing the Transatlantic Conflict over Agricultural Biotechnology: Contending Coalitions, Trade Liberalisation and Standard Setting (2006) and GM Food on Trial: Testing European Democracy (2010). Over the past decade his research themes have broadened to agricultural innovation priorities, the bioeconomy, corporate environmental stewardship, natural capital assessment, alternative agri-food networks and the agroecology-based solidarity economy in South America. As an early entry point into such issues, he participated in the Radical Science Journal Collective in the 1970s and 80s. The RSJ was replaced by a new journal, Science as Culture, on which he has served as co-editor.

Leonardo Marques

is Professor of History of the Colonial Americas at Universidade Federal Fluminense, Niterói. He has worked with themes related to capitalism, slavery and the slave trade in an Atlantic context for the last two decades, having published a large number of essays and two books on these topics. His first book, Por aí e por muito longe: dívidas, migrações e os libertos de 1888 (2009), explores the trajectories of former slaves in the last years of slavery and in the post-emancipation period in the state of Paraná, Brazil. His second book, The United States and the Transatlantic Slave Trade to the Americas, 1776–1867 (2016), explores the different forms of US participation in the transatlantic slave trade and how they changed over time. He is currently working on a global environmental history of mining in Brazil from the colonial period to the present.

Jamila M. H. Mascat

is Assistant Professor in Gender and Postcolonial Studies at the Department of Media and Cultural Studies, Utrecht University. Her research interests focus on Hegel's philosophy and contemporary Hegelianism, Marxism, feminist theories and postcolonial critique. She is the author of Hegel a Jena. La critica dell'astrazione (2011). She has co-edited Femministe a parole (2012); G. W. F. Hegel, Il bisogno di filosofia 1801–1804 (2014); M. Tronti, Il demone della politica. Antologia di scritti: 1958–2015 (2017); Hegel & Sons. Filosofie del riconoscimento (2019); The Object of Comedy: Philosophies and Performances (2019); and A. Kojève, La France et l'avenir de l'Europe (2021).

Wendy Matsumura

teaches modern Japanese history at UC San Diego. She is currently working on a project titled Japanese Grammar: Crisis and Oikonomics after World War I, which examines the relationship between oikonomics, imperialism and anti-capitalist struggle in the Japanese empire through a Marxist feminist perspective. Her first book, The Limits of Okinawa: Japanese Capitalism, Living Labor, and Theorizations of Community (2015), traced the contested emergence of Okinawa as Japan's exotic ‘South’ as part and parcel of the process of the former Ryukyu Kingdom's annexation and transformation into one of the empire's premier sites of sugar production.

Søren Mau

is a postdoctoral researcher interested in value-form theory, Marxist feminism, Marxist ecology and radical philosophy. He is the author of Mute Compulsion: A Marxist Theory of the Economic Power of Capital (2022), which is an attempt to build a theory of how the logic of capital reproduces its grip on social life by means of an abstract, impersonal and anonymous form of power. He is currently working on a research project on Marxism and the body, which will hopefully result in a book. He is a member of the editorial board of the journal Historical Materialism and a member of the board of the Danish Society of Marxist Studies.

Annie McClanahan

is an Associate Professor of English at the University of California, Irvine. She is the author of Dead Pledges: Debt, Crisis, and 21st Century Culture (2016). Her work has appeared in Representations, boundary2, South Atlantic Quarterly, theory & event, the Journal of Cultural Economy and elsewhere, and she is co-editor of the online, open-access journal Post45. She is currently completing a book titled Tipwork, Microwork, Automation: Culture after the Formal Wage.

Gregor McLennan

is Emeritus Professor and Senior Research Fellow in the School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies at the University of Bristol. He is the author of Marxism and the Methodologies of History (1981), Marxism, Pluralism and Beyond (1989), Pluralism (1995), Sociological Cultural Studies (2006) and Story of Sociology (2011); and he is the editor, with extensive commentary, of Stuart Hall, Selected Writings on Marxism (2021). He has also published a range of papers evaluating the contemporary entanglement of postsecularism, the postcolonial and critical sociology.

Sandro Mezzadra

is Professor of Political Theory at the University of Bologna, Department of Arts, and is Adjunct Research Fellow at the Institute for Culture and Society of Western Sydney University. In the last decade his work has centred on the relations between globalisation, migration and political processes, on contemporary capitalism and on postcolonial theory and criticism. He is an active participant in the ‘post-workerist’ debates and one of the founders of the website Euronomade. His books include In the Marxian Workshops: Producing Subjects (2018). With Brett Neilson he is the author of Border as Method, or, the Multiplication of Labor (2013) and of The Politics of Operations: Excavating Contemporary Capitalism (2019).

Salar Mohandesi

is an Assistant Professor of History at Bowdoin College. His research focuses on the transnational history of theory, social movements and political cultures in the wider context of war, revolution and imperialism. His current book project traces the history of anti-Vietnam War activism in France and the USA from the early 1960s to the late 1970s to explain how and why human rights displaced anti-imperialism as the dominant way of imagining internationalism in North America and Western Europe.

Roberto Mozzachiodi

is a doctoral student at Goldsmiths, University of London, a workplace organiser and a translator. He is a Visiting Lecturer at Regent's University. He writes on Francophone Marxist histories and philosophy.

Patrick Murray

is Professor of Philosophy at Creighton University in Omaha, Nebraska. He is the author of The Mismeasure of Wealth: Essays on Marx and Social Form (2016, 2017) and Marx's Theory of Scientific Knowledge (1988), and the editor of Reflections on Commercial Life: An Anthology of Classic Texts from Plato to the Present (1997). For Brill, he is working on Capital's Reach: How Capital Shapes and Subsumes and a reissue of Marx's Theory of Scientific Knowledge. With Jeanne Schuler he has co-authored a book manuscript under review, False Moves: Basic Problems with Factoring Philosophy. His research interests centre on the relationship between capitalism and modern philosophy and include the British empiricists, Kant, Hegel, Marx and the Frankfurt School.

Brett Neilson